STATEMENT: Black Caucus Protest at the African Studies Association, Montreal, October, 1969

Black challenges to white control of African Studies at the 1969 African Studies Association meeting in Montreal exposed the deeply entrenched racism within, and the imperialist leanings of, the field. Has anything changed?

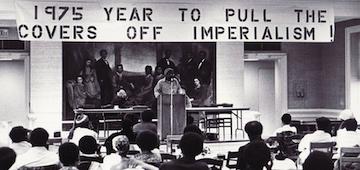

The contentious events surrounding the 1969 “confrontation at Montreal,” as the late historian John Henrik Clarke dubbed it, offer insights into the racist politics that have long poisoned the western study of Africa. On October 16, 1969, a group of Black students interrupted the opening plenary session of the joint meeting of the Association of African Studies (ASA) and the Canadian Committee on African Studies (CAS) in Montreal, Canada. In the presence of 1,700 conference participants, the students took the microphone from the conference’s invited speaker, Gabriel d'Arbossier, Senegalese ambassador to Germany, and castigated the ASA for its colonialist and racist practices. The students condemned “the intellectual arrogance of white people which has perpetuated and legitimized a kind of academic colonialism and has distorted the definition of the natural and cultural life and social organization of African peoples.” They described the ASA as “invalid” and “illegitimate” and declared the conference suspended until their charges were resolved.

As the Black Caucus proceeded to disrupt other conference sessions over the next two days, a group of radical white scholars, the Radical Caucus, offered their support. The Radical Caucus argued that the Black Caucus demands were not radical enough. They demanded, among other things, that the ASA and the CAS make clear their opposition to colonialism, neocolonialism, and imperialism, and that these organizations should be transformed to serve Black liberation. In response, the Canadian Committee on African Studies withdrew from the conference, perhaps because there was no racism in Canada. Or because Canadian Africanists would surely not have been involved in imperialism.

On October 19th, the leadership of the Black Caucus presented a motion to the ASA demanding the creation of a new board with full racial parity. The ASA’s existing board defeated the motion, 104-93. A compromise resolution, the Burke resolution, was presented after the Black Caucus resolution. It suggested the formation of a committee to study and report on how to change the ASA. The Burke resolution was passed. However, soon after the conference, ASA leadership declared that the proceedings and the resolution violated the organization’s constitution. As such, the resolution was moot. The ASA followed up with a questionnaire to its members about the direction of the organization. According to Ronald H. Chilcote and Martin Legassick, responses to the questionnaire suggested that “only twenty percent favored racial parity for blacks [sic] and whites on the ASA Board, while others advocated a ‘non-racial policy.’”

The Montreal ASA protests represented the explosion of a number of long-simmering tensions concerning structural issues in the study of Africa, fuelled, in part by the emergence of Black Power. Montreal, as writer David Austin has demonstrated in his studies Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in Sixties Montreal and Moving Against the System: The 1968 Congress of Black Writers and the Making of Global Consciousness, had already been radicalized by the legendary 1968, Congress of Black Writers, with its Black radical resonances across North America and the Caribbean. The Congress preceded the banning of Walter Rodney from Jamaica, the 1969 Sir George Williams Affair, and the wave of Black protest and repression that accompanied both. Meanwhile, 1968 also saw the formation of the Black Caucus at the ASA conference in Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, Black scholars and students, from Africa, the Caribbean, and the U.S., questioned not only why so many whites had suddenly become interested in studying Africa, but why they held powerful, decision-making positions in the field of African Studies. These Black scholars formed the African Heritage Studies Association and issued a statement calling for ASA to make itself more relevant to the difficulties experienced by the entire Black world. In the journal Africa Today, Black Studies scholars James Turner and Rukudzo Murapa described the protests as “a manifestation of historical schisms between Blacks who attempted to work in the field of Black Studies (i.e. Africa and the African diaspora) and the Whites who dominate and control the field.”

When the Black Caucus exposed the racism of the ASA, and the Radical Caucus pointed to the organization’s imperialism, they inadvertently revealed the true, white supremacist nature of the white Africanist’s study of Africa. “Racism here walks hand-in-hand with imperialism,” Chilcote and Legassick wrote. The institution of African Studies in the U.S. - and white rule over that institution - comes directly from US Cold War politics, the formation of the global US security apparatus, and the desire to exert influence and control over newly-decolonizing countries. “Area Studies” emerged at this moment and African Studies was quickly one of those areas of focus. The US government set up nine major African Studies Centers in major all-white universities including UCLA, Columbia, Johns Hopkins, and Northwestern. These African Studies centers were well-funded by the US government (through the National Defense Education Act) and wealthy foundations such as Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Ford. The centers supported the intellectual needs of US empire. As historian Paul Zeleza asserts, also in the journal Africa Today, the purpose of US African Studies was to reinforce “the national security imperative” of knowledge production about Africa. It is no secret that many of these white Africanists, especially social scientists, worked with the US State Department.

White money and white power enabled the triumph of the white Africanists’s “Africa” in the white academy. African Studies, housed in well-funded white universities, marginalized Black institutions. Well-funded white academics excluded Black scholars, training and hiring their own in an unending cycle of white supremacist social reproduction. White academics (from North America and Europe) continue to dominate the field of African Studies.

But before the US State Department established white African Studies, Black scholars and activists pioneered the study of Africa. The work of Black intellectuals including Edward Wilmot Blyden, W. E. B. DuBois, Carter G. Woodson, Eslanda Goode Robeson, Alain Locke, Arturo Schomburg, John Henrik Clarke, and many, many others have been bleached out by the white usurpers of African Studies. As a result, there has been a shift in the politics and objectives of the study of Africa. Black liberation was removed from the research agenda; Black people were transformed into objects of study by white Africanists. For these reasons, the Black Caucus demanded that the study of Africa return to its roots, that is should be undertaken “from a pan-africanist perspective, or Afrocentric perspective, which defines that all Black people are African peoples and negates the tribalization of African peoples by geographical demarcation on the basis of colonialist spheres of influence.” It is a demand that still needs to be heard.

In an effort to renew this radical, pan-African call for the study of Africa, the Black Agenda Review reproduces below the two statements produced by the Black Caucus in Montreal.

I. Statement of the Black Caucus Made to ASA Plenary Session, The Morning of October 16, 1969:

We, the Black people gathered in Montreal on October 15, 1969, on the occasion of the annual conference of the African Studies Association, having long disapproved of the complexion, activities, direction and selection of participants of this organization and its conferences, hereby state the following:

1. This organization which purports to study Africa has never done so and has in fact studied the colonial heritage of Africa.

2. We condemn the intellectual arrogance of white people, which has perpetuated and legitimized a kind of academic colonialism and has distorted the definition of the nature of cultural life and social organization of African peoples.

3. The work of this organization is irrelevant to the interests and needs of Black people and the methods of research are geared toward proposals which extend the old material interests of the European nations.

4. International research controlled, directed and financed by Western interests is a subtle, but potent, mechanism of social control and exploitation of African peoples and resources.

5. The granting agencies which support African Studies are the same people and organizations which exploit African peoples throughout the world and undermine and retard our political development. We are aware of the presence right here of people who represent those interests.

Therefore, we resolve that this organization and its work are fundamentally invalid and illegitimate. Its present relationship to Africa is damaging and injurious to the welfare of African peoples.

We further resolve that this conference shall be, and hereby is, suspended until the following matters have been resolved satisfactorily:

A. We unconditionally support our Black brothers and sisters who are presently being held as political prisoners in this city as a result of their stand taken against blatant racism practised against them by a white professor at Sir George Williams University. In a very real sense this conference does not relate in any way to the serious problems confronting those Black people and the Black community in general in Montreal.

B. The direction and content of African Studies must come from Black people through an international Pan-African organization along the lines of the African Heritage Studies Association. Therefore the offices of the African Studies Association are declared vacated and this Ad Hoc Committee assumes control so that Black people can determine future definition and content of African Studies.

II. Statement of the Black Caucus Presented To The Board Of The ASA On the Evening of October 19, 1969, Submitted To The ASA membership For Informal Vote On The Morning Of October 17, 1969, And to the Fellows For Formal Vote On The Afternoon Of October 17, 1969, When It Was Rejected By The Fellows Who Then Voted In Favor Of The “Burke Resolution”:

African peoples attending the ASA conference have demanded that the study of African life be undertaken from a Pan-Africanist perspective. This perspective defines that all black people are African peoples and negates the tribalization of African peoples by geographical demarcations on the basis of colonialist spheres of influence. This position was enunciated at the negotiating meeting with the Board of Directors of the ASA this afternoon.

Specifically, in order to reflect this perspective, African peoples demanded that the following changes be made in the ideological and structural bases of the organization which purports to study, research and teach authoritatively about African peoples and culture:

1. The ideological framework of the ASA, which perpetuates colonialism and neocolonialism through the “educational” institutions and the mass media, should be changed immediately.

2. The constitutional procedures, which provide for the election of a predominant White Board of Directors to decide upon the scholarship, study and research of African life should be changed immediately to deal truthfully and realistically with African peoples.

3. In accordance with the above, the new Board of the ASA should be composed of twelve members — six Africans and six Europeans.

4. That the ASA give financial support to the African students of Sir George Williams University in Montreal, Canada, who are now political prisoners of a colonist government, and that the ASA make a strong public statement indicating its abhorrence of the situation.

5. The rules governing the membership of the ASA be amended so as to allow African scholars total participation in the Association.

6. The criteria for allocation of funds for research and publications on the study of African life should be established by a committee composed of equal numbers of Africans and Europeans.

In a plenary session of the African peoples, it was unanimously agreed to reject the ASA Board's token offer of three African representatives on a twelve-member Board of Directors, the other nine being elected according to regular procedures. The plenary session of African peoples considered the ASA Board's offer irresponsible and insulting.

The plenary session reiterated that African peoples will no longer permit our people to be raped culturally, economically, politically and intellectually merely to provide European scholars with intellectual status symbols of African artifacts hanging in their living rooms and irrelevant and injurious lectures for their classrooms.

Reprinted from Africa Today, Vol. 16, No. 5/6, The Crisis in African Studies (Oct. - Dec., 1969), pp. 18-19.