Vincent Harding’s reflections on the expansion of Black Studies in the 1960s offers an ominous warning on the hiring of Black faculty and administrators today.

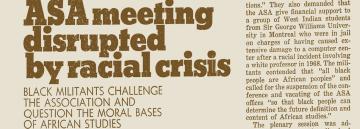

The keck of white guilt in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in 2020 saw white universities scrambling to hire Black faculty and white foundations desperately throwing money at Black anything. The moment has echoes of 1968, at least when it comes to the white university. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., many white, northern institutions rushed to develop Black Studies programs and great promises were made concerning the recruitment of Black faculty and, to a lesser degree, Black students. Unfortunately, unlike in the 1960s, when there was serious debate about the nature of Black Studies, and the role of Black faculty, within both Black and white universities, today’s hiring sprees have been largely scattershot and reactive affairs, responding in a knee-jerk fashion to calls for “diversity and inclusion,” with little attention to long-term questions of retention, growth, and permanence – let alone intellectual content or political mission or the autonomy of Black institutions.

In the late 1960s, Black World/Negro Digest, the Johnson Family publication edited by the great Hoyt W. Fuller, provided an important platform for debates on Black education. Across three March issues in 1968, 1969, and 1970, Black World hosted a discussion on “The Black University.” While all three issues are worth revisiting, historian Vincent Harding’s essay, “New Creation or Familiar Death? An Open Letter to Black Students in the North,” seems particularly relevant for the present. Harding, who, at the time was on the faculty of Spelman College, worried about the effects of the migration of Black faculty and Black students from Black schools in the South for more lucrative, if significantly whiter, institutions in the north. The loss of intellectual power was an issue, as was the question of financial imbalance. But for Harding, the larger question concerned what Black Studies would become if it was unmoored from its roots in the Black community and transposed to “Ithaca and Berkeley.” Would Black, southern institutions remain viable when Black Studies and Black faculty were transported en masse to “rural Ohio and upstate New York”?

Not all of the writers in Negro Digest shared Harding’s worries. And certainly, many of the conditions of the present were not anticipated by Harding’s concerns in the past. Today, the gutting of the intellectual and political content of Black Studies has enabled the spawning of Blacks in the upper levels of the white university administration: not only the hiring of Black diversity officers and multicultural liaisons, but also of Black deans, Black provosts, and even Black presidents. Neoliberal Negroes abound in the white university. The integrated Blacks have become not only the face of diversity, but the arm of austerity: they come as a two-for-one package deal of intersectionality and inclusivity and strike-breaking and budget cutting. Meanwhile, for both faculty and students, what Harding called “jiving” is merely building your brand and getting your bag. Harding’s essay is a reminder that Black Studies could have had a different path. Read it below.

New Creation or Familiar Death? An Open Letter to Black Students in the North

Vincent Harding

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

This letter may touch on sensitive and painful areas, but it is based on the assumption that every contradiction within our struggle must be examined with relentless care and discussed with total candor throughout the brotherhood of our blackness. On the other hand, it must also be clear that I do not assume that those of us who work out in the academic halls of the South are any more free from powerful and ironic inner confusions than you who operate in the North. Nevertheless, there are certain current developments among you which appear dangerous — indeed disastrous — from our perspective. We are convinced that no meaningful building of the Black University can take place unless at least some of these issues are resolved. So I have taken it upon myself to try to articulate our general concerns, especially as they are directed to those of you who study and teach on northern campuses.

Let me get to the point in the most brutal manner first, and then attempt to elaborate with greater precision as I go. The center of our cancer is this: Do the black student (and faculty)brothers in northern schools realize that much of your motion over the past year has often appeared to encourage the destruction of those colleges and universities where some 125,000 black students study in the South? Besides, do you realize that such action towards destruction puts you in league with many white, northern, academic administrators who are ready to deny the future of black southern education, ready to manipulate the death of potentially powerful black institutions?

Now, let me say more fully what I mean. Over the past several years, for dozens of good, bad and indifferent reasons, the schools of the North have been discovering that they need black students, faculty persons, and various levels of black-oriented curriculum. (As you well know, the current commercial value of blackness has not been one of the least of the reasons for the belated and somewhat sudden awakening.) As might have been expected, these white institutions turned increasingly towards the black campuses of the South. There they found a ready-made supply of black faculty, and discovered the presence of some Afro-American curriculum which had not been destroyed by “integration.” In addition, they began to enter into serious competition with the southern schools for the best black students.

All this action was facilitated by the ready access such institutions had to the very financial sources which had been traditionally parsimonious in their help to black schools for some of the same tasks. (Of course, it should also be said loudly that the brain-draining process was significantly aided by the great hesitancy on the part of many faculty persons and administrators in the “predominantly Negro” colleges to realize that our experience as a people was worthy of serious academic exploration, and by their failure to offer the younger black scholars these encouragements which money cannot buy. But that is another article!)

Then came the assassination of our brother in April, 1968, and many of you stepped up the pace of your action a hundred-fold. Wherever you were gathered on the northern campuses, whatever your numbers you demanded more faculty, more courses, more black students than ever before. “Freedom, Now!” Became “Blackness, Now!” So you rapped with articulate vigor, boycotted, threatened all kinds of things, took over meetings, classes and buildings — and generally raised hell.

Meanwhile, we watched from the South. We applauded. We laughed at trembling white administrators who seemed ready to offer you everything you demanded — sometimes before the words were dry on leaflets. Occasionally we joined in the action on your behalf, and strengthened our own students in their resolve to their own southern thing.

As a matter of fact, when an increasingly large number of us were wafted through the skies to visit your campuses as consultants and lecturers and to become objects of tempting salary offers, some of our egos were momentarily bolstered (or our minds momentarily deranged) beyond description. Our black academic forefathers [sic] had never known such high adventure, we thought.

Now, for a variety of reasons, a blessed but painful clarity has begun to break into our euphoric white visions. We realize now that this situation is clearly neither a matter for laughter nor for self-gratification. Rather it seems evident that we were — and are— being tempted to sell out the black colleges of the South. And it appears no less evident that many of you were—and are—unwittingly acting as agents in the process, being used by persons who are not unwitting at all.

What we see in the new black light is that we are being called upon by the northern administrators (though your voices are often the ones on the phones) to give our energies, our course outlines, and finally our full-time talents to these institutions. So, for instance, programs in Afro-American sStudies begin to spring up from Ithaca to Berkeley, and we are invited to help staff them all. Again it also appears that northern-based financial sources are more ready to fund Afro-American Studies in rural Ohio and upstate New York than in the heart of the black South. This means, of course, that it is possible for the northern schools in the post-assassination period to offer salaries sometimes fifty to one hundred percent higher than the black schools — to say nothing of space, time, atmosphere and assistance for research and publishing.

Not only is this happening to us as faculty persons, but we watch as you count your numbers on the campuses. We hear you demanding more black company, especially from among the ranks of the brilliant brothers and sisters on the block, and it becomes clear what this means for us. It means that recruiters (now often black) from the North move more fully than ever before into the traditional southern territories of the black schools and offer fabulous scholarships and other financial aid to the best black students available. (They also offer, of course, the prestige of the names to a still prestige-conscious black community.) When college-bound brothers and sisters weigh these offers against those of the black schools (often late-moving black schools) it is understandably hard for them — for you to resist. Thus the southern colleges face increased deracination on every level.

By now it should be clear that this southern exposure provides a different perspective. Therefore, it is not a matter of our begrudging you the blackness you so sorely need in those bastions of whiteness. Rather it is a matter of letting you know how it looks to us. For instance, as the white administrators of the North (and South) explain their newly discovered love for black students and faculty, and their sudden conversion to black studies, we who are the objects of that bulldozing love had to hear more than the words which are spoken. We think our southern position allows us to hear essentially these sentiments form the keepers of the embattled educational establishments:

“We are determined to get our black multi-tokens up here,” They say. “If we don’t do it quickly we’ll lose money, status and perhaps some of our nicest buildings. Therefore, we have learned well our lessons from the black communities hero, and we are determined to get students, courses and faculty members by any means necessary. If that involves the destruction of the black schools of the South, so be it. We never thought very much of them anyway. We’ve got the money and prestige to buy everything, even loud-talking, gun-toting militants.”

Indeed, just as this letter to you was being completed, to black students from Northwestern came into my office at Spelman. I had met them during one of my visits up North two years before, and now they were in Atlanta returning the visit — and recruiting black students for Northwestern. Just as I was presenting to them some of the central concerns of my letter, the phone rang and the long distance operator introduced the voices of an old acquaintance — a dean at a prestigious white institution in Pennsylvania.

He said he wanted to know if there was any directory of black scholars available, or if I had a list I could give him because his Afro-American student organization was demanding black faculty representation in every department of the college. He had already seen a piece of writing in which I had decried the raping [sic] of black schools, but he was calling anyway, he said.

I told him that I was quite serious in my published position and therefore had no intention of giving him such a list when we needed in the black schools every excellent black scholar we could find. At that point, he produced a fascinating and revealing response, one worth reporting. HE said, “You realize, of course, that there are many persons in the north schools who have serious questions about whether those institutions should continue— at least as black schools; and that is one of the reasons why they have no hesitation about attempting to draw from them whatever faculty they can.” The conversation came to a more or less abrupt halt after that, and I reported it to my friends from Northwestern for the same purpose that I report it to you: to ask whether you have pondered the implications of such attitudes as you make your moves.

Of course, when we consider the past performances of the colonizing world, the attitude of the white administration should not startle us. The “Metropolitan” areas have had no more qualms about sapping the human, creative resources of their colonies in a later period than they did about claiming the physical resources in an earlier, more blatant time. Nor should “good intentions” becloud the issue; for if they do exist anywhere, they do not in any way lessen the impact of the attitudes which make the so-called “brain-drain” possible. Whatever has suited the purpose of the colonizers has been defined as good and necessary, whether it takes place between Brussels and Leopoldville or between New Haven and Atlanta.

Nor does it matter that the term has sometimes been “assimilation” and at other times it has been “integrations.” Ultimately it spells destruction of the heart of the colonized people if it is not stopped. Ultimately it is reminiscent of Harold Cruse’s lament for the cultural (now followed by the physical) destruction of the heart of Harlem. Finally, when we remember the historical attitudes of white northern institutions towards the black schools of the South, we are not surprised. For the current action fits well their pattern of basic unconcern about the needs of black life.

What does surprise and trouble us is the way in which many of you brothers and sisters on the northern campuses are participating fully in the patterns of our command destruction. I say “common destruction” out of a conviction that whatever diminishes the life and vitality of any significant black institutions (especially those which have been rooted in our history and which are now being pushed to an encounter with our essential blackness) is a destroyer of us all. So this letter comes as an urgent fraternal message, raising what is for us a crucial set of concerns.

Assuming that we are no longer committed to the individualistic ethos of America, nor to integration as it has so far been defined, and assuming that one of our major goals is the building of new levels of solidarity within the black community, I wish to raise the following questions for serious discussion:

1. As you assess the total struggle and your own particular situations in the North, in what ways may those of us who teach on southern campuses be of greatest help to you? How much of our energies should be spent in consulting and lecturing in the North at your request when there is so much business to take care of down here?

2. Many of you have been involved in attempts to recruit us to teach full-time on northern campuses, urging us to take the 3-to5- year appointments which we have been offered. How do you reconcile this position with the needs of the thousands of black students in the South? (Though I have no inclination to play the numbers game, it is important to consider the fact that the black student group usually numbers less than 100 on most northern campuses, and 400 is an unusually large figure — though it often represents a minuscule percentage of the total student body. On theater hand, you ask us to leave campuses with black student populations ranging from 500 to more than 5,000).

3. If we really intend to make the search for the Black University more than good rapping material for a hundred conferences, then where can we take the best concrete first steps — on a white campus or a traditionally “Negro” one? Especially when we consider the service the black university must render to its immediate community, is it contradictory in the extreme to consider such nation-building service coming from “black universities” in overwhelmingly white institutions?

4. One former professor at a well-known “Negro” University recently announced to the world that he will do his black thing from now on at a predominantly white school. He made this decision, he said, because back school eventually will be more likely to imitate a good thing if it happens in a white context first. Without using such words, other black faculty persons have evidently taken a similar point of view. How does that way of producing blackness fit into our rhetoric concerning the needs of the community? Is it really more imitation that must have now?

5. Considering our sadly limited resources, can there be more than a few really excellent programs or institutes in Afro-American Studies in this country? Is it possible that the recent announcements of the creation of at least two dozen research programs will lead to even more dispersion of our black talents, rather than to the consolidation we so badly need for this period? If only a few such black research and teaching centers can live with significant integrity, where should they be developed? Indeed, where will they find nature during a period of prolonged struggle?

6. To move to an even more directly personal level, have any of you considered the possibility that it might make more sense to bring 50 black students to a black-oriented professor in the South than to take him away from his campus? In other words, have you questioned your own locations seriously in the light of our need to gather ourselves together?

7. Have you given serious thought to your own sense of vocation? The building of The Black University, whether it be realized in one or a dozen locations, demands totally committed teachers, organizers and administrators who have moved beyond jiving to real work. What about you? (Perhaps you don’t know that black students in the South, on the “negro” campuses, are also calling for more black faculty. When will we find them?)

These are, as I said, questions for discussion. Though they may sound rhetorical and loaded at points, they are not meant to stifle debate. IF they seem unfairly weighted they simply bear all the freight of my own fullest concerns for our future in this strange land.

Even as I raise the questions, though, I am well aware of the fact that many of you have currently excellent reasons for staying on the northern campuses where you are So, as we develop those discussions which must question and reexamine both the southern and northern black academic positions, I wish to add a few concrete suggestions for action, action with may make it possible for use to serve—rather than destroy-each other where we are now.

1. On the recruiting of black faculty for northern school: If this must be done during these days when the supply of well-equipped, black conscious brothers and sisters is so limited, then why not work for the establishment of special visiting professorships rather than outright raiding of black schools? Under such an arrangement faculty from the South could be invited for one year, we could teach one course in our specialty each quarter or semester and be available for many kinds of counseling. There would also be freedom from the many ordinary academic pressures of our southern campuses, and time (as well as secretarial and research assistance) could be made available for more research, writing and publication. At the same time we could not be wrenched away from the southern schools on an indefinite basis. In a sense, this would be no more than a token presence, of course, but it represents a temporary measure which might have some mutual benefit while we discuss the questions above and while we seek to increase the supply of brothers and sisters who can do the job.

2. On the recruiting of black students: there are obviously hundreds of thousands of black students outside of the colleges who ought to be involved in some meaningful experience of higher education. Since your institutions have obtained funds from many sources for some of this task, why not make at least part of that money available in more creative ways? For instance, a consortium of one or more white and one or more black schools could be created solely for the purposes of recruiting black students. Through some pooling of funds (mostly yours in the North), black students could then be approached with this offer: Here are the funds you need to go through college. You can use the money to attend (for example) Morehouse, Dillard, Cornell or the University of Illinois. If you choose a black school we ask only that you agree to spend one of your years on the predominantly white campus, strengthening your brothers there. If you choose an overwhelmingly white school, you will have the privilege of going “home” for a year. In this way black students could take the money from white schools and use it anyway they choose. Besides, under the new conditions now prevailing in both black and white institutions, the exchange could not help but be fruitful.

3. The issue of finances is a crucial one, especially as it relates to the future of black colleges. Some institutions would obviously serve the cause best if they merged with other schools to create new strengths and expanded facilities. But even those which remained needed to be enlarged and endowed in ways that black schools have not known up to now. Why, for instance, should it not be possible for prestigious northern school to use their prestige to help obtain special research grants for certain work which can be done all only by black scholars/ Or why should you more affluent northern institutions no be pressed to make other significant financial contributions to the life of these schools they now so blithely seek to rape [sic]? The United Negro College Fund might be one general depository. Others can be found. Perhaps an autonomous but well funded black educational foundation ought to be established, with its single mission the financing of creative ventures in black education. (This would not exempt the existing white foundations, of course; it would simply mean that this black institution would be able to give all of its time and energies to the task.) So far it has been relatively easy to get white institutions to perform certain kinds of money-rpdocuting acts on behalf of black education on their own campuses. Perhaps the time has come to press them to use part of their budgets, even sections of their endowment funds, to help establish such a foundation, or otherwise to make long-term substantial investments in the black academic institutions. These would, of course, constitute no more than preliminary steps towards restitutions (Certainly it is no accident that such proposals, fit the pattern of what the former colonizing nations must do to be of significant assistance to the areas they crippled.)

4. Finally, it is apparent in the current rush to blackness on the part of white institutions that there simply is not the beginning of an adequate supply of persons trained in Afro-American studies. It is imperative for us— and for you— that we move urgently to fill that gap in ways other than the stripping of the southern black campuses.

The various Institutes and Ph.D programs in this field which have appeared over the past year are obviously meant to meet the need (as well as to satisfy you and to keep you off certain backs) but I would argue that most of them can’t and will not do the job. (Indeed some of them may die as soon as you stop blowing.) On the other hand, it is only logical that black institutions in the black community, if properly funded, organized and led, could probably do the best job of creating new scholars in the field of Afro-American studies. This seems especially likely in those places where traditions, libraries and faculties seem at least adequate even now, and where students are pressing sometimes reluctant “others” towards blackness.

In Atlanta, that has been our basic assumption, and a group of us have moved towards the creation of such an Institute for Afro-American Studies. We think black students throughout the nation should know this, and should ponder its possible meaning for your own presents and futures.

As some of you know, there are in the Atlantt University Center six “Negro” institutions in various stages of their search for blackness. On the faculties are more than 30 persons whose training, experience and teaching in the field of Afro-American life and culture are at least significant. The Slaughter Collection of Negro Literature, the Georgia State Archive and the newly begun Martin Luther King Memorial Library (a documentation center for the Movement) combine to present unusual library and archival resources on black experience. Apart from such tangibles, we are also beneficiaries of the spirit of the great pioneering work in black studies done in Atlanta by such persons as W.E.B. Du Bois, E. Franklin Frazier, Rayford Logan, E.S. Brathwaite, Ira DeA. Reid and many others.

It is against this background of past and present resources that we are now in the process of creating an Institute for Afro-American Studies under the umbrella of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Center. Research, teaching, celebration and action are to be the central driving forces — all focused on the life and times of the peoples of African descent. I mention the Institute here because it will need many things which you can help provide. It will need millions of dollars, the best staff from every part of the African diaspora, students who are ready to take care of business, and it must have continuous exposure throughout the black community. The schools you attend could help raise funds for this Institute. For they will need our products (both human and informational) if they are to retransformed into viable situations. Some of you will ultimately compromise the staff and student body. The plans you now have for Afro-American studies in white settings must be reexamined and challenged by Atlanta.

In short, I am proposing that you help this Institute become the major black educational creation of this generation. You have a kind of leverage in the white world which must not be dissipated in minor, ambiguous victories. More importantly, you have a power which must not be turned against meaningful black institutions. The challenge to help create such an institute, to break down the many brittle assumptions of conventional American education, to move consistently towards our intellectual roots in the struggle for liberation—this is, I think, a challenge. More appropriate to your power.

As you ponder these matters, I trust you will remember that my questions and proposals are meant to be only some of the ingredients in a dialogue which must take place among us. The letter is written in the spirit of ecumenical concern as we move towards a new humanity. The words are my own, but the concerns are shared by many other persons on the southern campuses. We look forward to appropriate responses from North, East and West.

In the struggle,

Vincent Harding

Spelman College, Atlanta, Georgia

Vincent Harding, “New Creation or Familiar Death? An Open Letter to Black Students in the North,” Negro Digest (March 1969).