One year since the murder of community leader and poet Tchadenksy Jean Baptiste, his dedication and love for his nation and his people lives on.

Port-au-Prince is on fire. Not since Haiti rose from bondage to defeat the 60,000-strong army of Napoleon and all of the French empire’s reinforcements of tens of thousands of mercenaries has Haiti confronted such a dire moment. Paramilitary gangs armed to the teeth with U.S. weapons terrorize entire communities in Port-au-Prince and Latibonit.

Buried within the hellscape of hunger, overflowing garbage and sewage, with gun battles brewing on every korido (alleyway) and kwen (corner), there is resistans.[1] Who are the nameless, fearless warriors who keep fighting for another Haiti beyond paramilitary and foreign control? How can we highlight their stories of hope as the corporate media feeds us nothing but anti-Haitian and anti-Black stereotypes? How can we be in solidarity with the popular movement in Haiti during these critical weeks when the U.S. prepares its next invasion? At a historical moment when colonialism has sought to bury the Haitian people’s collective self-esteem, the smiles, the courage and the love still burst forth. Thank you Tchadensky! Mèsi Tchadenksy! Souri w ouvri wout pou Ayiti. Pwezi ou te viv e mouri pou peyi a. Byento ase Ayibobo.[2]

Last year, on Tuesday, March 21st, a sniper’s bullet from an Israeli-made Galil ripped through the flesh of 24-year-old Haitian community leader and writer Tchadenksy Jean Baptiste. The war in Port-au-Prince counts among its victims hundreds of thousands of children and families who have been burnt out of their homes, raped and murdered. In Sniper City, death squads battle each other, the organized and unorganized masses and the police for territory and power. The police are among the favorite targets of the mercenaries, with on average 15 officers murdered every month in the capital. Amidst the imperial maelstrom, despite the bullets, gangs and hunger, community and resistance leaders continue their work, steadfast and confident in their people, their ancestors and their spiritual way of life. Armed with his perennial smile and poetry, Tchad was one such example of a determined militan (member of the organized protest movement) who never ceased to believe in and fight for Haiti’s unfinished second revolution.

“Pa Gen Moun Pase Moun” (No one is better than anyone else)

To walk with Tchadensky in the korido yo (alleyways) of Belè, Fò Nasyonal and Port-au-Prince’s many sprawling, perilous slums was to walk shoulder to shoulder with revolutionary royalty. In neighborhoods where the battle for hegemony plays out between criminal, paramilitary organizations and the masses, every neighbor, every elder and youth knew him and looked up to him. He didn’t believe in eating alone. Children gathered around cement blocks or big boulders that served as makeshift tables eagerly waiting to see what their big brother had cooked up for them. His habit of always sharing his hot plate worried his mother who perennially wondered if her oldest son had eaten enough. The elders reminded younger generations that this collective approach flowed from lespri aysyen (the Haitian way or soul).

Squatting in front of a ripped poster of Jan Jak Dessalin, on a side alleyway off John Brown Avenue, the 24-year-old speaks to a group of Rasta youth: “We fight for everyone to be treated like the dignified human beings that they are.” He stopped mid breath and mid sentence and pleaded with his political family: “Why are we losing this battle? How do we take our neighborhoods back?” Despite fleeing from home to makeshift shacks and then sleeping in the streets, in stadiums, abandoned buildings and in public parks alongside hundreds of families displaced by the proxy death squads, Tchadensky never stopped reading and writing. He cited Soviet leader Mikhail Kalinin who taught that it was important to find time to read and write even if it was on the battlefield. Tedina, his life partner, remembered him as a prankster, a chef, a perfectionist, a scholar, an indefatigable fighter and lover of life.

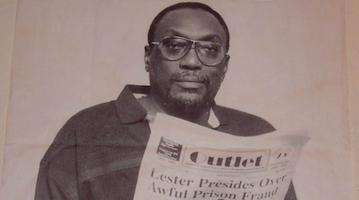

Tchadensky performs his first love, poetry.

“I don’t have time for hate. I only have time for love.”

A year after his death, the university where Tchadensky studied and performed has yet to come to terms with their loss. His close friend and colleague James Junior Jean Rolph offered his own eulogy, reminiscing that this youthful renaissance man did not “have a big head, constantly motivated his peers, worked and progressed without complaining and always had his head in the books.”

Tchadenksy, like so many in this city of 2.5 million, lived on the run. He remained a light in Port-au-Prince’s most infamous neighborhoods 一 Matisan, Delma 2, Kafou Fèy and Belè. These are the bidonvils (ghettos) that provide the canvas for the clips of unrestrained violence that circulate on Haitian whatsapp. Tchad and the movement rejected the sensationalism of the media. Internally within MOLEGHAF and other socialist organizations, they discouraged the sharing of what they saw as “Black Death Pornography.” Tchad and others cautioned against the sharing on Whatsapp of grizzly images of heads cut off, sexual violence against the most vulnerable, bodies tortured and massacres. After a deep breath, he patiently explained to a crowd that they and their self-esteem had been brutalized and traumatized enough. The insurgent’s responsibility was to re-instill hope and love in the masses. And this is what our protagonist did until he was again run out and his home, alongside thousands of others, was burnt down. How many poems, memories, dreams, libraries and futures have disappeared in the flames, smoke and ashes of imperialism? For some militan, what they most lamented after the loss of life, was the loss of memories. How many bookshelves of fresh literature and newly-written poems have been sacrificed at the altar of the U.S. government’s obsession with guns, violence and plunder?

Haiti’s top newspaper, Le Nouvelliste, published the poet’s last words “Running, Always Running” which has survived the author and the hybrid war[3]:

“Running, Always Running"

I am always on the run

Until I am out of breath

I am not an athlete

I am no type of sportsman

But I am always running

I am fleeing and hiding from stuff I did not do

After Lasalin

I am in Aviyasyon

I sprint through Dèlma 2

All I know how to do these days is run

Drenched in sweat

I am running out of breath

I’m not running

To get in better shape

Or to impress anyone with a 6-pack

I run because I am on the run

I have my backpack on

My baby is in my hands

I have blankets wrapped around me

I grab any last memories I can

I drop my passport in the fury

I search for a corner

A nook and cranny

To rest my weary head

My exhausted body

To think of the life I completely lost.

We all run

We run together

Our grandmothers

Little ones

Everyone

United

Running

Some of us are burnt

Others are on fire

All of us running

shoulder to shoulder with the trauma

To see who will cross the line of death first.

After Kanaran

I run through Divivye

Then Site Solèy

We are all running

Drenched in sweat

We are running out of breath

We search for a hiding spot

A refuge

Where we can maroon the bullets

So the stray bullets

Do not

Swallow us whole

On the path

where we are running”

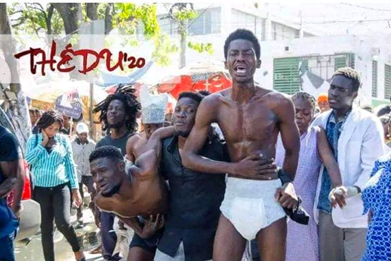

A march to remember the families massacred in 2019 in Lasalin who were stripped naked before being butchered.

David vs Goliath

And on a Tuesday, like any other, surrounded by one of his usual extended families, Tchadensky suddenly went quiet and crumbled underneath his own weight. The children saw the bleeding wound on the side of his stomach and screamed out “Amwey! Tchadenksy pran bal.” “Help! Tchandenksy was shot.” Amidst the shock, his comrades scrambled to gather the money necessary to pay a motorcycle to bring him to The Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) hospital.

According to Domini Resain, Coordinator of Mobilization for MOLEGHAF, (Movement for the Equality and Liberation of All Haitians), the student leader was organizing a community meal and a workshop for children displaced by the gang war when a sniper blasted a bullet from an IMI Galil into his abdomen. Everyone speculated: “the sniper who shot Tchad, was he a police officer, a paid assassin or a gang member from the G9 or G-Pèp paramilitaries who have know reconstituted themselves under the command of Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier as the Viv Ansanm alliance (Live Together)?” Domini intervened before a crowd who gathered to express their condolences: “Does it matter who killed Tchad? They are all the same. These are not stray bullets as they claim. They are state bullets. These are PHTK bullets. These are police bullets. These are Washington bullets.”

In the “Confessions of a Haitian kidnapper,” police officer Arnel Joseph unpacks the secret connections that exist between political and economic power elites, the Haitian National Police and the gangs. While the dominant narrative carried by telejòl (television or media reports carried by mouth or through rumors) stated that a stray bullet struck the popular leader, the militan were quick to point out that these were state bullets and Washington bullets.

As Peter Hallward’s classic book, Damming the Flood: Haiti and the Politics of Containment, on the rise and repression of the Lavalas movement shows, all of modern Haitian history is a contest for power between the desperately poor 99.9 percent and the fabulously opulent 0.1 percent of the Petyonvil mountain enclave. In this asymmetrical war, Tchad mobilized poems, smiles and flowers as his class enemies hired professional assassins for a cheap day’s pay. How many tens of thousands of Lavalas organizers and fighters from the broad social movement have been disappeared, exiled, imprisoned and assassinated?The oligarchy disappears the expression, art and leadership they deem to be an obstacle to their rule. If anything remains clear in Haiti, it is the fact that a handful of elite families hide behind their heavily-fortified castles and the carefully curated media they own and manage. There are more private security guards than public police in the most unequal country in the Western hemisphere. It was an entire system that murdered Thadensky, like so many others from his generation.

A smile as eternal and irresistible as one of Tchadensky’s poems

Washington Bullets and Resistans Ayisyen (Haitian Resistance)

The average life expectancy in France is over 82 years. The average life expectancy in The Dominican Republic is 73 years. In Haiti, it is 10 years less. For a revolutionary in Haiti, the statistic drops several more decades. Tchadenksy joined a growing list of community leaders liquidated under the rule of the PHTK, the Haitian Bald Headed Party, named so because their first dictator, Michel Martelly was bald. The party's rule is especially sinister because they hide behind their hired mercenaries, denying any involvement. Paramilitaries are more effective in Haiti, just as they were in Colombia, Argentina, El Salvador and other U.S. neocolonies because they are not accountable to anyone.

The modern makouts (thugs and assassins) are loyal to Izo, Kempès Sanon, Barbecue, Vitalhom or whoever the local warlord is. Three survivors of a kidnapping in Mon Kabrit, who do not want to be named, explained: “The young recruits didn’t have money to eat that day but they gripped AR15s and AK47s worth over $10,000 on the streets of Haiti. We know they are involved with the drug trade. How can they get such expensive weapons when most of us are hungry? When they divided the men from the women (the speaker looked down), the kidnappers screamed allegiance to their leader Lanmò San Jou (Death without a day announced). They asked us who we were loyal to…which political party or gang? Refusing the debate, we looked away. They hit us and reminded us that their president and the president of all of Haiti was their boss, the paramilitary gang leader, Lanmò San Jou.” This anecdote is telling and sheds light on the highly localized reality of gang bosses who preside over their own fiefdoms of looting, raping and destruction. This is the colonial Haiti run by guns for fire that Tchadensky resisted, and the one that ultimately consumed him and thousands of other innocents.

The notorious warlord and ally of Barbecue, Kempès seeks to burn Fort Nasyonal and Solino the ground.

Our protagonist never hesitated to denounce the powers that be, “the gangsters in ties” and foreign forces who fanned the flames of the fratricidal war. The griot articulates what so many know but cannot express or are deathly afraid to express – the chaos in Haiti has its origins faraway in the palaces and boardrooms of Washington D.C., New York, Miami, Ottawa, Montreal and Paris. While CNN, Fox and the New York Times deceitfully portray Haiti as isolated, the Caribbean nation of over 11.5 million has for centuries been integrated into the international capitalist machinery.[4] And if the maroon nation ever steps out of line, U.S. Marines are not far off to remind them of their place in the global pecking order. Washington now prefers mercenaries from Brazil, Kenya, Chile, Chad, Nepal or Benin to carry out their fourth invasion and occupation of Haiti in the past 100 years.

Regardless of the historical odds, there is an abundance of leaders and organizations who trained with Tchadensky and are fighting to elevate their homeland out of the neoliberal quagmire. They too are survivors of this hybrid war. Highly conscious of the ideological and media war against them, MOLEGHAF, the Black Panthers of Haiti, model another brand of leadership, honest, self-sacrificing and anti-imperialist.[5] For this reason, they have been targeted by state and paramilitary bullets. Many political demonstrations and protests in Haiti are in front of the U.S. embassy precisely because of this anti-imperialist awareness. Dahoud Andre, a spokesperson of KOMOKODA, the Committee to Mobilize Against Dictatorship in Haiti, and host of "Haiti Our Revolution Continues" on WBAI analyzed the ins-and-outs of the struggle today for Haiti’s definitive self-determination on Black Agenda Radio.

On the anniversary of the death of a Haitian Fred Hampton, take time to resist the mainstream clichés against Haiti and share the memories of our Haitian saints. The Gregory Saint-Hillaires, Jean Anil Louis Justes and Tchadenskys gave everything for everyone, while awaiting nothing for themselves in return, as they fought and fell in combat in order to guarantee all the homeland’s children an abundance of water, food, peace, liberty, dignity and joy.

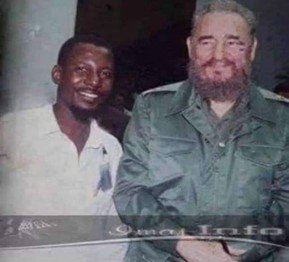

Professor Jean Anil Louis Juste, here with the eternal comandante of the Caribbean, was assassinated hours before the 2010 earthquake for being a free thinker and organizer against the PHTK dictatorship.

Fanmi Lavalas (Sali Piblik)

KRÒS Kowòdinasyon Rejyonal Òganizasyon Sidès yo

MOLEGHAF: Mouvman pou Libète Egalite sou Chimen Fratènize Tout Ayisyen

OTR: Òganizasyon Travayè Revolisyonè

Radyo Resistans

SOFA: Solidarite Fanm Ayisyen

Rasin Kanpèp

Konbit Òganizasyon Politik ak Sendikal yo

Tèt Kole Ti Peyizan

MPP Movman Peyizan Papay

Movman Popilè Revolusyonè (Sitè Soley)

Sèk Gramsci

Sèk Jean Annil Louis-Juste

KOMOKODA (Komite Mobilizasyon kont Diktati an Ayiti Committee to Mobilize Against Dictatorship in Haiti)

Jounal revolisyonè: La Voix des Travailleus Revolutionaire

Platfòm Ayisyen Pledwaye pou yon Devlopman Altènatif

SROD'H: Syndicat pour la Rénovation des Ouvriers d'Haïti

ROPA: Regwoupman Ouvriye Pwogresis Ayisyen

OFDOA :Oganizasyon Fanm Djanm Ouvriye Ayisyen

Altènativ Sosyalis

Fwon Popilè e Patriotik

JCH Jeunesse communiste haïtien

[1] All spellings are in the national language of Haiti, Kreyòl, not the colonial language, French.

[2] Translation: “Your smile opens up a new path for Haiti. Your poetry lived and died for Haiti. See you again soon comrade God bless!”

[3] For the original version of the poem in Kreyòl see the embedded link. With permission from Tchadensky’s family, I translated the poem into English.

[4] The Haitian state last conducted a census in 2003 under the leadership of Jean Bertrand Aristide so the population is probably much higher than 12,000,000.

[5] Partial List of Leftist, Anti-Imperialist Organizations in Haiti

Danny Shaw teaches Latin American and Caribbean Studies and Race, Ethnicity, Class and Gender at the City University of New York. He holds a Masters in International Affairs from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. He is fluent in Spanish, Haitian Kreyol, Portuguese and Cape Verdean Kreolu. A professor at Midwestern Marx Institute and author of "The Saints of Santo Domingo: Dominican Resistance in the Age of Neocolonialism," he works to keep young people out of the military and prison industrial complex.