Featured image: A Man Crying amid the Rubble of His House, Southern Lebanon, 1982- 1988. The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, The Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS) Collection

Dr. Charisse Burden-Stelly provides important context to “Moving Towards Life” which examines how the issue of Palestine changed the relationship between June Jordan and Audre Lorde.

At a rally in Detroit Michigan on Wednesday, August 7, 2024, Kamala Harris chided pro-Palestine protesters. As they chanted “Kamala, Kamala You can’t Hide! We Won’t Vote for Genocide!” the self-proclaimed “top cop” shot back, “You know what? If you want Donald Trump to win, then say that. Otherwise, I’m speaking.” This open contempt displayed by the presumptive presidential nominee for the Democratic Party came exactly two weeks after she met with Benjamin Netanyahu and reiterated the United States’ unwavering commitment to the right of the colonial entity (“Israel”) to exist, and by extension, to continue its war-intensified genocide of Palestinians. Harris’s actions demonstrate not only disregard for the Palestinian people but also deep contempt for the forces who actively oppose their annihilation.

The same day Harris condescended to Palestinian activists, a piece titled, “Moving Towards Life” was published in the LA Review of Books. It juxtaposed the positions of two Black feminists, June Joran and Audre Lorde, on the question of Palestinian liberation, and analyzed the fallout between the two given their opposing positions. For example, Jordan penned an open letter criticizing her close friend Adrienne Rich, who had taken on the position of a Zionist feminist after the start of the Israel-Lebanon War in 1982 and equated anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism. Lorde, Barbara Smith, and other Jewish and Black feminists blocked the publication of Jordan’s letter, claiming it assassinated Rich’s character, promoted division between Black and Jewish feminists, and demonstrated insensitivity to Jewish people. While in her letter Jordan took responsibility for the colonial entity’s violence and Palestinian suffering as a U.S. citizen and taxpayer who hadn’t done enough to stop the “holocaust and genocide,” Lorde et. al engaged in an identitarian defense of Rich and “the Jewish people” that was more concerned with Jordan’s tone and “insensitivity” than the colonial entity’s ongoing, war-intensified aggression against Palestinians.

Two concepts, intersectional imperialism and identity reductionism, are relevant to understanding Lorde and her feminist counterparts’ use of Black and Jewish identity to bludgeon Jordan’s righteous critique of the colonial entity. Intersectional imperialism describes the ways that U.S. imperialism is rationalized, legitimated, and continued by employing the language of intersectionality, appointing racialized and minoritized people to strategic positions, and foregrounding marginalized individuals as mouthpieces of empire. Identity reductionism relies upon reactionary and class-devoid appeals to intersectional identities and individualized “lived experience” to drown out structural and material analysis, historical and dialectical materialism, and political and ideological commitment as legitimate bases for understanding a particular phenomenon.

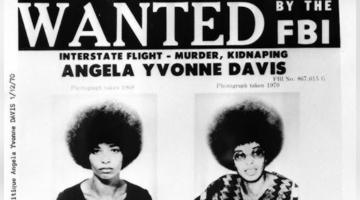

Not unlike our current moment, “Moving Towards Life” conveys Zionism’s interruption of solidarity and the pitfalls of supporting Palestinian liberation. Jordan’s pro-Palestine position hampered her career, even amongst fellow feminists of color, while Lorde’s relative acquiescence on the matter prior to 1989 ensured her international celebrity. Similarly, Kamala Harris is championed by a large swath of U.S. women and feminists even while her investment in genocide, in word and deed, is deeply unpopular with the global majority. Her stated support for U.S. women’s reproductive rights seems to take precedent over her genocidal foreign policy. Despite her tepid call for a ceasefire, the Biden administration released another tranche of funding for aggression against Palestinians—this time 3.5 billion dollars – to purchase US weapons and military equipment. Not even forty-eight hours later, the colonial entity committed one of its most heinous massacres since October 7, 2023, murdering and maiming hundreds of Palestinian women, children, and men at al-Tabi’in school and Mosque in the Al-Daraj neighborhood of Gaza City, a designated safe zone. Harris’s response to the carnage was to reaffirm the colonial entity’s right to “go after the terrorists that are Hamas” and to call for the release of (Israeli, and not Palestinian) hostages while meekly reproaching the number of “civilian casualties.”

An important takeaway from the Lorde-Jordan dispute is that it is never too late to take a principled position. Eventually, Rich, Lorde, and Smith became anti-Zionists and supported Palestinian resistance. They had Jordan as a model given her “uncompromising commitment and… willingness to lose friendships and opportunities by standing against the Israel lobby.” For those of us, then, who are unwavering in our support for complete Palestinian liberation by any and every means required, it is our historical task to win them to this position—and to the struggle against U.S. imperialism and Western domination more broadly. Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign is a pivotal time to remain steadfast in our position and to combat the Black misleadership class’s use of intersectional imperialism and identity reductionism to discipline silence, and hijack struggles for liberation and self-determination in the name of “protecting our freedoms, delivering justice, and expanding opportunity.”

Moving Towards Life

Marina Magloire

Exploring the correspondence of June Jordan and Audre Lorde, Marina Magloire assembles an archive of a Black feminist falling-out over Zionism.

Originally published in LARB.

IN FEBRUARY 2024, the Palestinian writer Mosab Abu Toha posted a picture on Instagram of a stack of books that his brother, Hamza, had rescued from the rubble of a recently bombed home in Gaza. At the top of the stack, amid broken slabs of concrete and severed iron bars, was a copy of The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (1997). It is fitting that Palestinians would be drawn to Lorde’s searing critiques of racism and imperialism. Lines like “So it is better to speak / remembering / we were never meant to survive,” from her poem “A Litany for Survival,” hold powerful resonance for Palestinian resistance to Israeli misinformation and censorship, for example. In her oft-quoted Oberlin commencement address in 1989, delivered three years before she died, Lorde addressed the plight of the Palestinian people directly: “Encouraging your congresspeople to press for a peaceful solution in the Middle East, and for recognition of the rights of the Palestinian people, is not altruism, it is survival.” However, many people do not know that Lorde’s critique of the Israeli occupation and her brief assertion of Palestinian rights in this speech were not a constant feature of her life and activism.

Lorde’s journey to a pro-Palestine stance was slow and halting. In Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), Lorde describes her youthful optimism about the creation of Israel: “[T]he state of Israel represented a newly born hope for human dignity.” That youthful optimism shouldn’t be surprising: in 1948, Lorde was only 14 and a student at Hunter College High School, where she was surrounded by young, eager, newly formed Zionists. It was, in fact, her friendships that shaped the way she thought about the issue for the rest of her life. By 1982, she was being pushed by a conflicting set of forces. Strongly on the Palestinian side was Lorde’s fellow poet June Jordan. Lorde and Jordan had a lot in common: both women were Black queer feminists born to West Indian immigrants in New York, and both were former professors in the City University of New York system. Both would eventually die of breast cancer. Until 1982, Jordan and Lorde were warm acquaintances, as well as colleagues and interlocutors; they shared political alignment on many issues relating to race and gender. But Jordan’s last written words to Lorde, after an extensive epistolary disagreement over Zionism, were “You have behaved in a wrong and cowardly fashion. That is your responsibility. May you […] live well with that.”

Jordan has recently been much-touted as an example of Black women’s solidarity with Palestine, as evidenced by lines from her 1982 poem “Moving Towards Home”: “I was born a Black woman / and now / I am become a Palestinian.” But the context of the fateful year that inspired Jordan’s writing of this poem—the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the Israeli-backed massacres at the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila—is seldom discussed, nor is the full scope of Jordan’s lifelong commitment to Palestinian liberation. Considering Jordan’s dedication, why was it Lorde’s book amid the rubble, and not hers?

Jordan is lesser known nationally and internationally than Lorde, and it seems to me that her decades of unwavering support for the Palestinian people is partly responsible. Jordan’s vocal anti-Zionism hamstrung her career for nearly a decade, resulting in death threats, a loss of writing opportunities, and social ostracization within multiracial feminist circles. Even in the time since her death, Jordan’s pro-Palestine stance has made her less co-optable into a neoliberal diversity narrative in which Palestinian liberation has been taboo for decades. Lorde is famous for the maxim “Your silence will not protect you,” but in this case, Lorde’s initial silence on Palestine did protect her career and her flourishing afterlife as a patron saint of the oppressed. Meanwhile, Jordan’s decades of writing and advocacy on behalf of the Palestinian people have been woefully underappreciated. Jordan once wrote, “I say we need a rising up, an Intifada, USA,” and for her, intifada was not a metaphor. Unlike Lorde, Jordan intended her writing to be a weapon, a public act in the service of Palestinian liberation. Despite their biographical similarities, Jordan and Lorde had differing practices of solidarity. How can we add nuance to the historical narrative of Black feminist solidarity with Palestine? After all, even 40 years later, US-based solidarity movements are still threatened by the same fault lines that felled Lorde and Jordan’s friendship.

In June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon and began a nine-week siege on the capital city of Beirut, targeting the regional Palestinian resistance movement. During this war and the ensuing carnage against Palestinian refugees led by Israeli-backed paramilitary groups, over 20,000 Palestinian refugees and Lebanese civilians were killed. In his 2020 book The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017, Rashid Khalidi argues that “because of American backing for Israel and tolerance of its actions […] the 1982 invasion must be seen as a joint Israeli-US military endeavor—their first war aimed specifically against the Palestinians.” Back in the United States, mainstream media publications like ABC, NBC News, Time magazine, and The New York Times reported for the first time with sympathy on the Palestinian struggle and displayed outrage at Israel’s atrocities. Amy Kaplan argues in Our American Israel: The Story of an Entangled Alliance (2018) that Israel, during this war, “had lost the claim to innocence that it had maintained during prior wars. Its messaging was no longer unassailable, and its worldview no longer smoothly nor automatically reflected that of the American news audience.” In August 1982, even Ronald Reagan called to admonish Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and wrote in his diary that “the symbol of [Begin’s] war was becoming a picture of a 7 month old baby with its arms blown off.”

This was perhaps a particularly callous moment for American women to express a commitment to Zionist feminism, but Jewish feminists in the US had been divided over support of Israel since its creation in 1948, and in the 1970s, the wider feminist community of the United States frequently engaged in heated debates about Zionism in feminist periodicals and at women’s studies conferences. Enter Adrienne Rich, preeminent Jewish lesbian poet and longtime advocate for the oppressed. Both Jordan and Lorde were dear friends of Rich, and both carried on a decades-long personal and professional correspondence with her (now housed in their respective archives). Today, Rich is known as an anti-Zionist poet—she was active in anti-Zionist Jewish organizations beginning in the mid-1980s, and in 2009 endorsed an academic and cultural boycott of Israel. But in the summer of 1982, she flirted briefly with the idea that perhaps it was possible to be both a feminist and a Zionist.

In an open letter published in the feminist journal Off Our Backs in July 1982, Rich joined six women who went by the collective moniker Di Vilde Chayes, Yiddish for “the wild beasts,” on an open letter titled “… What Does Zionism Mean?” All the signatories self-identified as “Jewish lesbian/feminists of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) background.” Despite their awareness of the “complexities” of Israel’s displacement of Palestinians, Rich and her cosignatories were unequivocal about Israel’s right to exist: “Zionism is one strategy against anti-Semitism and for Jewish survival. Anti-Zionism is Anti-Semitism” (underlined in the original). Perhaps most galling of all was their claim that anti-Zionism was also racist, “since it refuses to acknowledge that two-thirds of the Jews of Israel are people of color.” Aside from the fact that this statement was authored entirely by white American Jews, this concern for the plight of Jews of color still seems dubious—it reads more like a rhetorical tool designed to shut down debate from other people of color than a genuine bid for coalition-building.

Even after Israel’s war of aggression against Lebanon dominated the American news cycle that summer, Di Vilde Chayes doubled down on their commitment to Zionism, publishing a second letter in October 1982 in Off Our Backs and WomanNews. They continued to position themselves as “Zionists—committed to the existence of Israel—who are outraged at Israel’s attack on Beirut and are equally outraged at the worldwide anti-Semitism that has been unleashed since the invasion of Lebanon.” Irena Klepfisz, a signatory on both letters, later regretted the timing of the letters, which “made us seem indifferent to the brutal events” of the war. Much like their initial response, even Klepfisz’s remorse is colored by the desire to “seem” evenhanded while making false equivalencies between an unspecified antisemitism and the concrete reality of 20,000 Arabs massacred (a form of rhetorical bad faith that persists to this day.)

Jordan felt betrayed by these letters. She had been friends with Rich since 1976, and their personal correspondence depicts a deep intellectual comradeship in which the two poets exchanged work, ideas, and emotional support. Later, Jordan recalls being shocked by Rich’s letter, given that in all of their previous conversations Rich had never identified as a Zionist nor as Jewish. It would seem that Rich had fallen into a common trap of 1980s feminism, as identified by Jewish Marxist Jenny Bourne: “To be accounted for politically has, for Jewish feminists, meant if not a clear competition with black feminists, an attempt at least to jump on their bandwagon and mechanically equate their struggle against oppression.” It’s certainly easy to imagine Jordan questioning her intellectual bond with Rich at this point, particularly after Rich labeled the political stance of anti-Zionism as racist, all while staking a claim to racialization and Third World struggle that did not reflect her lived experience as a white American woman. The power differentials between Jordan and Rich—who was older, more famous, and white—might have further exacerbated the former’s sense that the latter’s support was predicated on Jordan’s Blackness being merely identitarian and not political.

“It should surprise no one that we, Black and Third World people everywhere, attach fundamental importance to the question of Palestine,” says Jordan in her response to Rich’s statement. Driven by her grief and outrage at the massacres at Sabra and Shatila in September 1982, in which thousands of Palestinians were murdered by militia groups over the course of two days, Jordan wrote an open letter called “On Israel and Lebanon: A Response to Adrienne Rich from One Black Woman,” dated October 10, 1982. Her address to Rich was both personal (she names Rich alone among the signatories of the two letters) but also pedagogical (it is an open letter to be published in WomanNews and thus intended for public consumption). Using the words “genocide” and “holocaust,” Jordan lays out the shocking array of war crimes committed by Israel over five months—phosphorous bombs, the destruction of civilian infrastructure, the massacre at Sabra and Shatila—and criticizes Rich’s failure to take responsibility for these things as the tangible outcomes of the Zionism she claims to espouse. This idea of responsibility runs through Jordan’s response like a live wire, culminating in this astonishing statement:

I claim responsibility for the Israeli crimes against humanity because I am an American and American monies made these atrocities possible. I claim responsibility for Sabra and Shatilah [sic] because, clearly, I have not done enough to halt heinous episodes of holocaust and genocide around the globe. I accept this responsibility and I work for the day when I may help to save any one other life, in fact.

Because Rich does not take responsibility, Jordan models it for her. This is perhaps the most important rhetorical turn in Jordan’s letter, though it goes unacknowledged in subsequent responses from other readers. Jordan recognizes that being part of an ethnonationalist state, whether born or chosen, carries the obligation to critique its violence. The fact that a Black woman born in this nation can make this statement, with far more humility than Rich’s selective, cherry-picked identification with Israeli statehood, is a testament to the transformative possibilities of Jordan’s identity politics.

Jordan’s open letter was never published, due to the intervention of a group of Black and Jewish feminists, including Lorde; it exists only (as far as I have seen) in the unpublished archive of Lorde’s correspondence. Based on her cover letter to the editors of WomanNews, Jordan had sent copies to other Black women writers whom she viewed as friends or interlocutors, including Alice Walker, Toni Cade Bambara, and Barbara Smith. Some of these women might have provided support for Jordan through phone calls or other ephemeral forms of communication, but there are no letters from any of them in Jordan’s correspondence archives from the fall of 1982. Far from supportive, Smith forwarded a copy to Lorde, who agreed to join Smith and eight other women in writing a letter to the editors of WomanNews to block the publication of Jordan’s response on the grounds that it “contributes to an atmosphere of increased polarization between Jewish and Black women.” (The copy in Lorde’s archive appears to be a Xerox of Smith’s direct copy from Jordan, which was headed by a handwritten message: “Dear Barbara wanted you and Cherríe [Moraga] to know this is happening. Best, j.j.”) Although they agreed with Jordan that “the Vilde Chayes’ two open letters reflect insufficient political concern for the fate of the Palestinian people,” the letter’s signatories thought that Jordan’s singling-out of Rich was tantamount to “character assassination.” They argue that Jordan demonstrates “insensitivity to Jews as a group” by questioning Rich’s self-identification as a Zionist and point out the fact that Di Vilde Chayes wrote their second letter before Sabra and Shatila (though it was published after) and thus cannot be accused of being indifferent to it. They lament the fact that Jordan “did not express her anger toward the group’s politics in a responsible way.” Overall, their reply seems more interested in chastising Jordan for her tone and timing than in engaging with the content of her four-page critique. (Jordan notes this in her response: “That you assume that I knew when Rich’s statements were written as against when they were published and that you thought that should matter as much or more than what her published statements said, in fact, are further facts about both of you that I find bizaare [sic] and disgusting.”)

In a blistering response to both Lorde and Smith, Jordan writes:

Do not call me an anti-Semite. Bridle your fucking arrogance and let a little reality into your mouths […] I will match both of you anytime anywhere on the subject of who is veriably [sic] unswerving in her activism against such evils as anti-Semitism (anti-Jews and anti-Palestinian and anti-Arab, per se) and in her activism to produce effective coalitional politics.

Indeed, in 1982 alone, Jordan’s multiple expressions of outrage against the war in Lebanon through poetry, prose, and public speaking engagements echo loudly against the silence and equivocations of the feminists who sought to suppress her open letter.

The record of this correspondence is collected in Lorde’s archive at Spelman College, in the folder containing her correspondence with June Jordan. There is no written correspondence, in Lorde’s archive or in Jordan’s, between the two women after 1982. Jordan and Rich, on the other hand, rekindled their friendship after a four-year gap and continued to be close until Jordan’s death in 2002. In an interview with Peter Erickson in 1994, Jordan detailed her falling-out and reconciliation with Rich. When both were participating in an anti-apartheid poetry reading in New York in 1986, Jordan approached Rich and said, “I completely and absolutely detest your views on Israel and I love you.”

Meanwhile, letters to Jordan from other writers, such as Rich, Smith, and Alexis De Veaux, would sometimes ask things like, tentatively, “Have you heard Audre is sick again?” but Jordan wrote no further letters to Lorde. Unlike with Rich, the Jordan-Lorde rift was not only a matter of Lorde’s views on Israel—it was also a deeply personal betrayal of one Black woman by another. “So much for dialog/support/any kind of community,” Jordan wrote in her letter to Lorde and Smith. And of course, the personal was political—Lorde’s failure to identify with the Palestinian struggle over her personal connections with white women had heartbreaking implications for a solidarity movement in which Jordan often found herself alone, willing to be the only voice of critique in American cultural spaces overrun by Zionists. In her essay “Life After Lebanon,” Jordan describes being surrounded and harassed by “large whitemen, two of them Israeli poets” at a poetry reading, and the intercession of three of her friends who got her out of the venue. She was acutely aware of the necessity of community support against the very real threats that Zionists could pose to the health, safety, and careers of vocal anti-Zionists. Lorde’s support could not only have made a difference for Jordan personally, but it could also have marked a small but important shift in the political landscape of Palestine solidarity in the United States, which has only recently begun to achieve more mainstream traction.

Perhaps Jordan was moved to give Lorde a phone call before her death, and because of the nature of the archive, their reunion was left unrecorded. Perhaps she said, “I completely and absolutely detest what white supremacy has done to us and I love you.” Or perhaps, as Alexis Pauline Gumbs notes, their reconciliation was in some ways too late—Jordan’s next written words to Lorde were posthumous, in an unpublished tribute written a year after Lorde’s death. Jordan acknowledges that, in spite of the divisions wedged between them by racist ideologies, she and Lorde were striving for a common goal: “At different points our lives diverged as did our chosen paths for struggle[.] But we did not ever fully disentangle from joined combat against hatred and the annihilation of all bigotry[.]” On her part, despite this divergence, Lorde kept the somewhat unflattering record of her falling-out with Jordan as part of her meticulously self-curated archive. Why do that if she had entirely let go of their friendship? I think Lorde continued to walk with Jordan long after their paths diverged.

In her poem “Intifada Incantation: Poem #8 for b.b.L.,” Jordan writes, “I COMMIT / TO FRICTION AND THE UNDERTAKING / OF THE PEARL.” These lines can be taken as a mantra for Jordan’s role in pressuring members of her community to identify with and assume responsibility for the plight of the Palestinian people. Perhaps we can even infer that Rich’s eventual anti-Zionism, and probably Lorde’s, was generated by the friction of Jordan’s uncompromising commitment, and by the example of her willingness to lose friendships and opportunities by standing up to the Israel lobby. Jordan’s Black feminism was predicated on refusing the empty privileges afforded by life within what she called “the Big House” of the United States, where Black people have the unique opportunity to “throw salt or arsenic in [the] soup.” Jordan’s conflicts were meant to be (and were) galvanizing, an attempt to encourage her sistren to use their positionality to sabotage the US war machine.

Jordan was a deeply sophisticated internationalist thinker with a materialist understanding of solidarity. Like a searchlight, her poetry and essays swing from South Africa to Nicaragua to Cuba to Hawaii to Iraq, often in support of their movements for liberation and self-determination. Palestine fits naturally into the broad range of her anti-imperialist sympathies. Poems like “Moving Towards Home,” “Apologies to All the People in Lebanon,” and “Intifada Incantation,” and the essays “Life After Lebanon” and “Eyewitness in Lebanon,” demonstrate the long arc of a 20-year commitment to anti-imperialist struggles in Southwest Asia and the Middle East. These works are masterpieces of her ability to convert shame into political action—to move through the shame of complicity as an American taxpayer toward the responsibility of being among “Some of Us [Who] Have Not Died.” In later poems and essays, she never stopped fighting against the occupation of Palestine and against anti-Muslim and anti-Arab sentiment in the United States and Israel. After September 11, Jordan was in the final throes of her battle with cancer, but she still took the time to denounce the racism and Islamophobia animating the war on terror. Her friend, the Lebanese poet Etel Adnan, once wrote to her with wry approval: “They never forgive you for thinking that Arabs are human beings.”

What makes Jordan’s solidarity so enduring is that Jordan was not just concerned with the violence leveled against the Palestinian people but was also deeply inspired by the Palestinian resistance. This was quite radical in 1982, as Amy Kaplan argues—despite increased sympathy for Palestinian war victims, “the focus of the American media quickly shifted from the suffering of Palestinians to the anguish of the Israelis,” as American Zionists began to reframe the war as an aberration and a stain on the ultimately noble project of Israeli statehood.” Even today, a politics centered in Palestinian life, rather than in a redemption of Jewish morals, has proved sticky and divisive. Debates around the use of phrases like “intifada” and “from the river to the sea” have shown the limits of public sympathy for Palestinians as a people with demands for statehood rather than as passive victims.

Jordan was notable in her rejection of this framework, particularly in the way she used the word “intifada” in many of her poems and essays. “Intifada Incantation” is framed as an emphatic love poem written in all capital letters—the famous first line is “I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED / GENOCIDE TO STOP.” But the work isn’t just about two people. It takes the Palestinian people and their resistance as the starting point for love, home, and any semblance of life for a global community of the oppressed. It bears noting that the forces committing genocide in Palestine and Lebanon are the same forces that interrupted the communitarian love between Jordan and her Black feminist peers in the United States. Jordan’s poetic reclamations try to remind the reader of the true meaning of intifada, whose root word in Arabic means “to shake off.” What must we shake off in order to make way for the flourishing of love?

In Jordan’s handwritten notes for her 1990 essay, “Intifada, U.S.A.,” the word “INTIFADA” is repeated, like a spell, like a chorus to a song yet to be written. When Jordan visited Lebanon in 1996, we clearly see her commitment to intifada as a practice. During this trip, she took many photographs at the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, the sites of the atrocities she had raged against 14 years prior. Her photos and notes linger on the signs of life stubbornly creeping back into the landscape of the camps: clotheslines strung between blasted buildings, a young man ducking behind bullet-pocked stairs, women planting flowers. Like Lorde, we find Jordan amid the rubble, but in the latter’s case, it is her material presence: her sneakered feet, her hands clasping a camera, her yellow legal pad dutifully documenting the martyrs and those who survived. She was not content to merely lament Palestinian death from afar; she wanted to sit in the living room they created atop the ruins: “I watched a woman setting out a jasmine plant that would probably manage the atmosphere and, possibly, flourish.” Jordan’s model of solidarity is as arduous as the slow growth of this embattled jasmine, and it goes far beyond the cessation of genocide. If, as Jordan has it, “the issue of the Palestinian people is the issue of the value of human life,” Jordan teaches us to move towards life.

Featured image: A Man Crying amid the Rubble of His House, Southern Lebanon, 1982- 1988. The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, The Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS) Collection (0002.02.0058), palarchive.org. Accessed August 6, 2024.

Marina Magloire is an Atlanta-based scholar and the author of We Pursue Our Magic: A Spiritual History of Black Feminism (2023).

Dr. Charisse Burden-Stelly is an Associate Professor of African American Studies at Wayne State University.