Since Kamala Harris became the Democratic nominee for president, liberals have seen her as the next Shirley Chisholm. In this case, they are correct.

From virtually the moment that Democrats replaced Joe Biden with Kamala Harris at the top of the ticket, the media began to portray the Vice-President as Shirley Chisolm’s political heir.

In a somewhat shambolic essay published in the New Yorker a few days after Biden withdrew from the presidential campaign, the African American writer Jelani Cobb wrote:

In January, 1972, Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, appeared at a Baptist church in Brooklyn and announced her candidacy for President of the United States. Chisholm was a singular force in American politics of the time: her support for civil rights and legal abortion made her a pivotal connection between the interests of African Americans and the emerging, mostly white, reproductive-rights movement.

Three weeks later at the Democratic National Convention, the Reverend Al Sharpton told the audience:

Tonight we are going to realize Shirley Chisolm’s dream. Fifty-two years ago I was one of the youth directors in her campaign for president and 52 years after she was told to sit down I know she’s watching us tonight as a Black woman stands up to accept the nomination for President of the United States.

The constant references to Chisolm, however, are meant to do quite a bit more than merely celebrate yet another mile-marker in African Americans’ struggle for political equality. In referencing the late Congresswoman, writers, celebrities and pundits hope to delegitimize all opposition to Harris’ candidacy by intimating that it is based in the same racism and sexism–misogynoir is the popular term coined by social media–that capsized Chisolm’s presidential bid.

Continuing in the New Yorker, Cobb wrote of Chisolm:

But, despite her status as a trailblazer, her campaign—set against an entirely white, entirely male field of rivals for the Democratic Party’s nomination—was more often than not treated as a lark. The newly formed Congressional Black Caucus, of which she was a founder, did not endorse her. (Many members chose to support George McGovern, the eventual nominee.) The political calculations were clear: the nation would not support a Black woman, and the better play was to back a viable candidate who might eventually provide a return on the investment.

After noting that Harris did enjoy some advantages that Chisolm did not, particularly in fundraising, Cobb wrote:

But we have not entirely broken with hidebound, stagnant tradition. In 2008 and 2016, the Democrats offered up barrier-breaking nominees for the Presidency; the Party is batting .500 when it comes to actually electing such candidates. Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign inspired poetic musings about shaking off the moribund strictures of race, even as the first ripples of the eventual tide of racial backlash could be felt virtually from the outset. Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign was confronted with an unending assault of unfounded rumors, sexist insinuations, and conspiracy theories; Clinton spent far more time on defense than any successful candidate could. This year, we find ourselves yet again questioning the durability of outmoded presumptions about race and gender. It’s as if the nation has been running an experiment in which, at eight-year intervals, we test the impact of different kinds of identities in national elections.

What’s missing from Jelani’s comparison of Harris and Chisolm however is any acknowledgment that neither woman was especially progressive and in fact, stood firmly to the political right of the Democrats’ African American electoral base. Chisholm’s announcement speech at Brooklyn's Concord Baptist Church in January of 1972 anticipated Harris sharp disavowal of any race-specific policies that would benefit super-exploited African Americans. Said Chisholm in 1972:

I am not the candidate of Black America, although I am Black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women's movement of this country, although I am a woman, and I am equally proud of that. I am not the candidate of any political bosses or fat cats or special interests. I stand here now without endorsements from many big name politicians or celebrities or any other kind of prop.

I do not intend to offer to you the tired and glib clichés, which for too long have been an accepted part of our political life. I am the candidate of the people of America. And my presence before you now symbolizes a new era in American political history.

Chisolm did, in fact, augur a transition in U.S. politics although perhaps not in the way that she intended. The Black political class in 1972 was closely tied to the labor organizing and civil rights struggles of the postwar era, and as such, their policies were in virtual lockstep with African American workers who were in the vanguard of a nationwide mutiny.

When Chisolm tossed her name in the hat, employees were earning a larger share of national income–about 51 percent of GDP–than at practically any time in recorded history. Correspondingly, fewer Americans were living in poverty in 1972–about 1-in-10–than ever before, and the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans that same year took home their smallest share of national income, roughly 4 percent, than at any year in the history of the Republic. Couples married more and divorced less, and spent less of their income on housing, a kilowatt of electricity, or college tuition. Between 1970 and 1974, the number of African Americans enrolled in college increased by 56 percent, and white students by 15 percent.

Finding its voice following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the radical Black political tradition expanded its reach into virtually every sector of American society. In January 1970, St. Louis Cardinals’ center fielder Curt Flood sued Major League Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn for violating federal antitrust laws. At issue was the league’s reserve clause prohibiting players from filing for free agency once their contractual obligation to a team had expired. Flood, who had been traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1969, likened the clause to slavery, and attributed his decision to challenge baseball’s owners to the militancy in the streets, telling the players’ union’s executive board:

I think the change in Black consciousness in recent years has made me more sensitive to injustice in every area of my life.

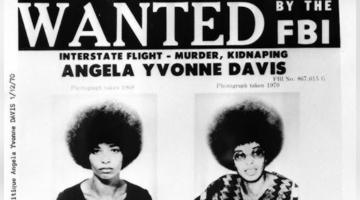

In contrast to Flood, Chisholm was not a revolutionary figure but a counterrevolutionary figure who was out-of-touch with Brooklyn’s large African American community. In a 1982 retrospective, the Washington Post wrote:

But she was on the opposite side of many women activists when, at the time the Small Business Administration was reauthorized, she opposed expansion of the definition of minorities to include women. Then she seemingly reversed her stand and led the fight for federal support of women's athletic programs. Last year Chisholm endorsed Mayor Edward Koch, while most other black elected officials charged him with personal bigotry and betrayal of his campaign promises. For her, she says, it was a pragmatic political move; her tone shows weariness from having to explain this alliance. She says she feels someone has to broker and bring accountability to the mayors who will gain new powers through the New Federalism. ‘I wanted to have my foot inside the door.’

She has been at odds with many of her black colleagues' personal goals and public stands. In the infant months of her first term, Chisholm opposed John Conyers for majority leader in favor of the late Hale Boggs. When Percy Sutton, then the highest-ranking elected black in New York politics, ran for New York mayor in 1977, she remained neutral. Her critics charge that she has stood outside elections where the minority and women candidates were trying to make the same historic steps she had made. They cite instances such as her not supporting former Rep. Bella Abzug (D-N.Y.) in one contest against Sen. Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.). Her local politics once caused New York's best-known black newspaper, The Amsterdam News, to editorialize on the "Chisholm problem."

New Deal liberalism continued to govern the country in 1972 and Chisolm was far to the left of Harris and the Congressional Black Caucus that endorses Israel’s horrific genocide in Gaza today. (The case can be made that Richard Nixon was to the left of most Democrats today, including Obama and the Clintons.) But you can trace the betrayals of today’s Black misleadership class to Chisolm’s overtures to white conservatives nearly 50 years ago. In 1977, just nine years after Martin Luther King was assassinated while protesting with striking black garbage workers, Atlanta’s first African American Mayor Maynard Jackson fired striking Black sanitation workers. Within a generation, Black elected officials across the country had become reliable votes in the Democrats’ efforts to militarize abroad and gentrify at home.

A key factor in the widening political divide is the theory known as intersectionality which posits that Black women are doubly discriminated against as a result of their race and gender. That is difficult to argue against but many critics contend that the notion has been widely misinterpreted to scapegoat African American men as the source of Black women’s subjugation. Many of Harris’ most visible supporters are gaslighting African American men’s legitimate political grievances against the Democratic party by characterizing as misogynistic any reluctance to vote for a Black woman.

The term “intersectionalism” had not been coined in 1972. Just two days after Chisolm announced her presidential campaign, the New York Times published a story entitled “Head of Operation Breadbasket Says He Opposes Mrs. Chisholm.” It read:

He said he would probably support a candidate running against her in the Congressional election this year.

Reverend Jones concluded on a prophetic note, summing up Chisolm in terms that aptly perform the political legacy not just of Kamala Harris, but Obama, Representative James Clyburn and a generation of African American politicians who have failed to deliver anything of value to their Black constituents.

“Mrs. Chisholm has played a significant symbolic role—more symbolic than substantial. The fundamental question is, ‘What has she done?’ I see no appreciable changes.”

Jon Jeter is a former foreign correspondent for the Washington Post, Jon Jeter is the author of Flat Broke in the Free Market: How Globalization Fleeced Working People and the co-author of A Day Late and a Dollar Short: Dark Days and Bright Nights in Obama's Postracial America. His work can be found on Patreon as well as Black Republic Media.