A 1971 interview with the late Charlene Mitchell reminds us of both the need for Black radical struggle against capitalism, militarism, and racism, and the contradictions of inter-racial organizing around US foreign and domestic terror.

Although the late Charlene Alexander Mitchell (June 8, 1930 – December 14, 2022) is among the most important radicals of the twentieth century, she is also among its least celebrated. The celebrity, fame, and notoriety that rained on many other Black radicals does not seem to have touched Mitchell and she has not been associated with a theoretical tendency or school of thought that bears her name. We do not speak of “Mitchellism,” and we do not have a backpack full of the glossy words or catchy phrases that she claims to have coined. While Mitchell left a modest bibliography of published works, she was an organizer, not a writer, and her true legacy is in the archive of her activism and political campaigns: in the campaigns to defend the Black Panther Party and the Wilmington Ten and to free Angela Davis, in her work as Secretary of the Youth Commission of the Communist Party of Southern California and directing the the Che-Lumumba Club in Los Angeles, and in her leadership of the National Alliance Against Racism and Political Repression (NAARPR) and the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. Notably, when Mitchell ran for the presidency of the United States in 1968 (the first Black women to do so) as the nominee for the Communist Party, it was for reasons of political strategy, not the narcissism of personality.

The textual record we do have of Mitchell is unfailingly luminous. In speeches, essays, editorials, and interviews, Mitchell has a political, theoretical, and moral clarity that is too often missing in the present. Mitchell is able to not only map the complexity and contradictions of the political world, but to clearly articulate a strategic path through those complexities and contradictions. Her unflinching, unwavering, and unrevised Marxism certainly helps in this regard. Read, for instance, the 1971 interview Mitchell gave in Cuba to Tricontinental, the Havana-based theoretical organ of the Executive Secretary of the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, or OSPAAAL. In the interview, Mitchell analyzes both the potential and limitations of Black-white alliance in the south, the importance of local anti-racist organizing to have an internationalist, anti-imperialist dimension, the dynamics of race as they cut across the demands of class, and the fact that while the Black struggle may be unique among Third World liberatory movements, it is not exceptional. And yet, Mitchell argues, Black liberation is foundational to any anti-capitalist project.

Charlene Mitchell’s interview with Tricontinental is reproduced below. It deserves serious study.

A Voice from the Monster

Charlene Mitchell

When in October of 1970, the forces of repression came down on the young black communist Angela Davis, a nationwide campaign to support her was already under way. It was organized, in part, by Charlene Mitchell who only a few months earlier, had been one of the organizing sparks for the emergency conference held in Chicago to defend the Black Panther Party’s existence against police attempts to liquidate it at gunpoint. Six months before that–as the Communist Party’s candidate for President of the United States–she had waged a spirited campaign to raise voter consciousness of a racist repression already well under way.

As is generally true for black Americans, struggle is a way of life for Charlene Mitchell. And hers has been political ever since her early participation in the antifascist and youth movements in Chicago, where she grew up and where she joined the Communist Party in 1948, at the age of 16. She moved to California and continued her activities in the mass freedom and youth movements, becoming Secretary of the Youth Commission of the Communist Party of Southern California. Since 1957, she has been a member of the National Committee of the CPUSA, and is a member also of the Party’s political committee of its Defense Commission, and secretary of its Commission on Black Liberation, among other posts.

On her first visit to Cuba, Charlene Mitchell outlined the recent history and the perspectives of the sharpening struggle within the United States–which we herewith present for our readers.

Could you trace the development of militant black political organizing in the United States over the past few years? What has been its ideology and its goals?

Up until very recently the black movement has had a very strong nonviolent character–best represented by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in its early days, and by Martin Luther King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). It sought, by pacifist demonstrations and verbal persuasion, to extend democratic rights to black people, mainly by registering them so they could vote in southern states. As you know, there were all kinds of violent reactions on the part of southern white officials and police, as well as ordinary citizens, culminating in the murder of Viola Liuzzo, wife of a Detroit trade unionist, who had come South for the Selma demonstration and to help the organizers. Following these events, the southern movement began to disperse and regoroup and SNCC began a very hardcore southern organizing drive in places like Mississippi and Lowndes County, Alabama. It helped to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party which, at the Democratic Party Convention held in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1964 (the year Johnson ran for office following Kennedy’s assassination) challenged the National Democratic Party to seat their black democratic representatives instead of the white racists who were representing the state of Mississippi at that convention. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party challenge was totally rejected by the National Democratic Party, which clearly had no intention of replacing Dixiecrats with blacks. SNCC then tried organizing a whole county–Lowndes County, Alabama–for the purpose of having the black residents of that county control its politics. It was here that the symbol of the black panther was first used.

Now, in all these drives, white youth had played an important role–namely that of giving advice to the black liberation movement rather than accepting leadership from it. They were young people, for the most part with good intentions, who found that they could not go into the Delta, could not go into the heart of the plantation areas to organize poor blacks–party because they were not used to the hardships of living in the South, and partly because they didn’t speak the language of the people, didn’t really understand their problems. So they wound up in administrative posts, giving advice to the black students and youth who went out into the field to do the work.

It was at that time that the leadership and the thinking in SNCC changed and Stokely Carmichael became its director. He raised the question–in my opinion correctly–of black people working among black people and made the simple proposition that if blacks were going to be organized, the organizing had to be done by blacks; and that if white people were serious about challenging America’s racist concepts, their challenge was to organize white people against racism. That only in this way could there be real unity, a unity established by blacks and whites working for the same ends in areas where each was best equipped to work.

Unfortunately, white youth did not know how to organize in the white community. In the main, they did not belong to the working class, but rather were from the liberal middle class with its democratic-humanitarian assumptions. For them, organizing white people should have meant going into the racist heart of America–and that, of course, became a very difficult thing to do.

It must not be forgotten that the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) came out of just such a liberal background, the offspring of social-democratic organizational parentage. At its founding, SDS had taken the position that it would have nothing to do with the communists and would allow no communists in its leadership. This placed it squarely within the acceptable framework of a “plague on both your houses.” That is to say, it condemned United States aggression in Vietnam at the same time that it condemned what it considered to be the undemocratic nature of communism. With respect to the Vietnam war, the position was, therefore, not pro-Vietnam but neutralist.

This position became more and more difficult to maintain as the United States increased its aggressive momentum and the anti-imperialist nature of the fight against that aggression became more evident. But at the beginning of youth’s involvement in the peace movement, they saw the fight as a democratic, humane, moral fight, in very much the same way that they saw the fight against racism within the United States as a democratic, humane, moral fight. Partly because of this liberal ideology and partly because of developments within the black movement, the white youth movement gave and has continued to give most of its attention to the war in Vietnam, while the black youth movement has placed most of its emphasis on the fight to organize and liberate black people within the United States.

This presented certain problems for both groups. The black liberation movement was correct in seeing racist oppression as the Achilles heel of American imperialism at home. But within the movement there were some blacks in leadership positions who were not revolutionary at all; were not interested in changing the capitalist system; who even tried to equate Black Power with black capitalism in an opportunistic effort to make capitalism work for them. And this segment was harmful to the black liberation movement. The more whites tended to concentrate solely on the war in Vietnam, the farther apart the two movements grew, until, by the time of the rebellions in Watts, Newark, Detroit, the white movement didn’t know what to do and the black radical movement felt itself isolated, without allies.

Has there been any left political activity that has recognized this problem and attempted to do something about it?

By 1967, there was a political attempt to begin an independent approach toward electoral politics, with the Communist Party assuming much of the initiative in attempts to forge some kind of left unity among those people directly concerned with the results of racism, those people active in the peace and student movements, and those organized elements within the working class who were critical of the pro-establishment labor leadership. This grouping organized what was called the New Politics Convention held in Chicago in 1967. But the Convention got off on the wrong footing when it developed its program, selected its leadership, organized its participants and then, when the plans were complete, invited the blacks in to take part. Many of us within the Communist Party became aware of this but it was already too late to reverse the situation.

The blacks had been denied leadership within this Convention and, because they had not been consulted, it was necessary for them to form a caucus within the Convention. The black caucus became, for the next period of time, a political way of life and an institutionalized procedure by which blacks could make their presence felt. (Unfortunately, too many whites have become comfortable with this situation.)

Within this Convention, ours became the only force capable of providing leadership. Black communists met with the black caucus, but we also met with our comrades–black and white–in the Communist Party caucus. We tried to reach conclusions that would enable that Convention to pull together around a progressive electoral campaign for 1967 and 1968, and it was pretty much agreed that the Communist Party saved what it was possible to save out of that Convention.

There were comparatively few organized workers at that Convention. This is important only in the sense that the Convention saw the beginning of the black caucus concept which, from then on, meant that black people would not meet with white people without first meeting among themselves and forming a highly centralized monolithic black position, and appointing their own leadership to state that position to whites. Because of lack of trust of the white lefts [sic] and liberals and the failure of whites to struggle against their racism, it became literally impossible to have any real black-white unity on how to confront the main enemy: capitalism.

The outcome of that Convention was the agreement that there would be an attempt to mount a third party ticket. Some saw this as a necessity in opposing the policies of the Democratic and Republican parties and representing the black liberation movement and the white progressive and radical movement in the 1968 presidential elections. Some saw it as a vehicle for essential community organizing, designed to raise political consciousness more than to win votes. And many of those who agreed to the first, minimized the importance of the second–and vice versa. This, along with many other problems, made it impossible for the New Politics Convention to carry out its own decision to run a national third party ticket.

So the Freedom and Peace Party ran one slate of candidates, headed by Dick Gregory for President. Peace and Freedom chose Eldridge Cleaver. Here were two presidential candidates, both of whom were black and neither of whom was able to get on the ballot in every state.

In California, the Peace and Freedom Party was on the ballot as a result of a number of things: the young people, along with others, had worked very hard to collect signatures and had found its efforts rewarded, in the midst of the signature campaign, by George Wallace’s successful signature campaign to guarantee himself a place on the California ballot. Therefore, many well intentioned people who never really intended to vote for Peace and Freedom party candidates, who never agreed with its program, registered themselves as party members in order to guarantee the far left along with the far right a place on a ballot.

It was at this time that the Communist Party decided it was absolutely necessary to run its own candidates for President and Vice-President: first, because there had been a failure to unite the left and progressive movements to the extent that a third party ticket could become a reality; and secondly, because it was the first time in 28 years that the Communist Party, because of the legal situation, was able to run a national candidate. We also felt it was necessary to present a real alternative to the questions of racism and war. And so, at our special convention, I was selected as the presidential candidate and Mike Zagarell as the vice-presidential candidate. We put forward a program of unity within which we raised questions that face the working class and the people of the United States generally. We attempted to point out why capitalism could not solve those problems and why a radical alternative was, therefore, necessary. With the concept of unity in mind, we approached both Eldridge Cleaver and Dick Gregory and agreed that we would see all three campaigns as complementary, and that there would be no attacks made by any of these candidates against each other but rather that they would all, in one way or another, serve to register the people’s feelings against the war and against racism.

Because the Communist Party was on the ballot in only two states–Washington and Minnesota–we took the position that people should vote for Eldridge Cleaver wherever he was on the ballot, and for Dick Gregory wherever he was on the ballot, because ours was not simply a campaign for votes, but to raise issues and the consciousness of the American people.

How would you describe the relationship of the Communist Party to other segments of the radical movement in the United States today?

Because of the repressive years, the Communist Party was decimated and we were unable to recruit any substantial numbers of new members. And over that period, a liberal anticommunism, as well as the repressive governmental actions, developed among many sectors. And along with it, there developed the ideology of nonpolitics–in the case of SDS the concept of participatory democracy. What this meant was that you need have no politics, no ideology, no leadership. Everybody did exactly as he pleased. It was sheer anarchy. But as people became more and more involved in the struggle, they began to see that somewhere you had to have an ideology. By 1968, many of them had decided they would become Communists–with a small c–not members of the “old’ Communist Party. They still sought to maintain an unguided revolutionary approach, relying on slogans as the motivating force; a quotation from Che or Fidel or Mao, or any of the worldwide revolutionary leaders, would become today’s slogan to move the masses. But MarxismLeninism as a scientific guide still had–and has–little meaning for them.

The Black Panther Party, on the other hand, although rooted among young black people who, for the most part, had not been in the workforce, came from a different background and heritage. Some were students like their white counterparts. Many had been in jail and, although not completely lumpen, were not really part of society. They considered themselves to be the heart of the movement, and the working class to be part of the middle class. If you had a job you were already suspect, especially if you were a member of organized labor. But by the time Huey Newton was arrested, he had begun very systematically to see the necessity for a revolutionary ideology. And it was within that context that the Black Panther Party began to move more and more to the left and to consider MarxismLeninism as its science, to be put into practice by organizing black people. And as they realized that the struggle is a class struggle, they began to find ways of having alliances with whites–alliances which our comrades have, of course, facilitated.

How do you view the relationship between oppression of blacks and oppression of other Third World minorities in the United States?

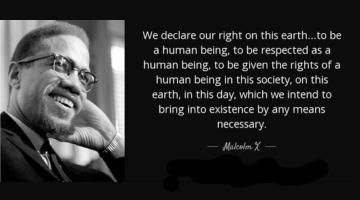

The struggle against oppression is a common struggle to get rid of the oppressor, but historically, because of the oppression that comes from slavery, and the fact of an entire people being the victims of capitalist oppression, it is different for blacks. It is different because blacks are the largest minority in the United sTates and the touchstone of capitalism’s ability to rule. A whole people are oppressed, regardless of their class, because they cannot be integrated into any level of the society that oppresses them and because they are overwhelmingly–95%–members of the working class. Blacks in the United States must be viewed as the central force around which the struggle against capitalism must move and the force that capitalism uses to keep the working class divided.

Other minorities–Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, Indians, Asians–are of course oppressed, discriminated against, denied equal rights and opportunities. But none of these groups is as large in numbers as are black Americans, more as generally dispersed throughout the country. Chicanos are chiefly confined to the Southwest, Northern California and a few in Chicago. Asians are in California and New York and are chiefly confined to the service industries–restaurants, laundries, etc.–rather than being integrated into the working class. Mexicans are chiefly in the Southwest and California. Puerto Ricans have generally come from Puerto Rico because of the conditions of poverty and colonialism under which they lived there. They have citizens’ rights in the United States but consider their real home to be Puerto Rico and their real fight to be the fight for Puerto Rico’s independence. And most of them are located along the Eastern seaboard. Black people on the other hand, live in every major urban area and, in the South, are part of the rural as well as the urban population. If the oppression of black people is removed, oppression of all other people will also be removed. Any victory for blacks affects other minorities, but it cannot be said that a token victory for other Third World minorities necessarily affects blacks as well.

This is the difference. But this is not to minimize the oppression of the other Third World minorities. It is simply to state the situation realistically–and the reality is a growing consciousness of the importance of Third World unity in the fight against oppression by capitalism.

Is there a growing realization that the struggle against imperialism abroad and racism at home are part of the same struggle against the capitalist system?

This realization is growing but it still has a long way to go. When Nixon made his speech on November 3, just prior to the big antiwar demonstrations scheduled for November 15, 1969, he announced the Vietnamization withdrawal plan. Because the peace movement in the main is a student movement and a youth movement, it is by definition young and inexperienced. Its slogans may be anti-imperialist and its anti-imperialist consciousness is growing. But Nixon’s announced Vietnamization plan caught the peace movement completely off balance. They tended to accept the concept of Vietnamization–and you can readily see the role that racism plays in this–to believe that, as long as United States soldiers were not doing the killing, it was all right for Vietnamese to kill Vietnamese. Even the moral character of the peace movement was forgotten in the eagerness to accept and “end” to the war.

At the same time, it became clear that the peace movement had not concerned itself with the repression of black people within the United States. Because it was at this time that the conspiracy trial was taking place in Chicago and Bobby Seale after being gagged and bound in court for weeks, was severed from that trial. There was not the same kind of demonstration by the peace movement against what happened to Bobby Seale as there had been against the war itself. And there was even a slowness on the part of his codefendants to react to this open act of racism in a Federal Court. There have been murders of hosts of black people, without any demonstrations opposing them. And even with the murder of the two Black Panther leaders in Chicago, when it became very obvious there was a conspiracy on the part of the Federal Government–executive, judicial, and administrative–that all these bodies had come together to smash the Black Panther Party, even then there were not the same kinds of mobilizations and demonstrations as had occurred during the period of the peace marches.

You may recall that more than two years ago, there was a killing by the National Guard in Orangeburg, South Carolina, of nine black students. They were shot in the back while demonstrating on campus. And there were no demonstrations.

When Nixon invaded Cambodia, the peace movement was totally unprepared. Had it really been as consciously anti-imperialist as some of us had thought, it would have started to move with the bombings of the so-called Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, it would have see that Laotian people were already living in caves, it would have been aware of the significance of Sihanouk’s plea to the Vietnamese to move out of Cambodia because of his fears of what the US was planning to do if they stayed. Had there been a real anti-imperialist consciousness in the peace movement, there would have been an awareness that a United States attempt at Vietnamization was not just to get troops out of Vietnam, but to regain control of all of Asia. But if you have an anti-imperialist consciousness based on morality rather than a fundamental understanding of the role of United States imperialism, then you are unprepared to stop a Nixon from invading Cambodia. And this is what happened to the peace movement.

The students who began to demonstrate against the involvement of the United States in Cambodia, seldom carried signs connecting it with Vietnam. This was true at Kent, for instance. So you see the spontaneous character of the protest, and the fact that the struggle against imperialism is not automatically connected with the right of people to have their national liberation.

So when the students were killed at Kent, the people’s movement was again taken by surprise. They did not connect the repression against blacks with the policy of moving the country more and more to the right. And so they did not assume that students who demonstrated against the invasion of Cambodia would be shot down by reactionary repressive bodies. And even much later, at demonstrations in Washington, the Kent students still did not understand the link between the killing of members of the Black Panther Party and the killing of their four student colleagues. The role of the left in linking these two questions, therefore, becomes extremely important.

In fact, I would say that the link has not been properly made for the international movement either. There was less publicity in the United States given to the killing of the black students in Augusta and Jackson, Mississippi, than to the killing of white students at Kent and the world press followed suit. So black killings have not received proper treatment in the press of the world movement. We in the United States have to be very critical of these differences because they affect our movement. And it is my opinion that the world movement, as well, is not cognizant of the tremendous importance to the world revolutionary movement of the black liberation struggle. They see national liberation in Africa, Asia, Latin America–but not in the United States. The world movement too must become aware that the struggle of black people for national liberation in the United States is absolutely necessary for the defeat of US imperialism.

How do you view the working class in the present struggle in the United States?

The United States working class is the most backward working class in the capitalist world. There is no real reason for it to be that backward, except for the fact that, according to Lenin’s Imperialism, a segment of the working class of an imperialist country can be bought off by that imperialism, and can collaborate with imperialism. They see their interests as being more involved with imperialism than with their own class. Such people have become the top leaders of the United States working class. They are class collaborationists. Many of the skilled workers have been able to raise their standard of living far beyond the majority of workers, because they enjoy the fruits of US imperialism. Capitalism is to their benefit. As a result, they have played the role, not of raising the class consciousness, but of delaying that process.

The working class, then, has tended to be extremely militant around its fight for wages, but has not had the same militancy even about working conditions. Because black workers had, in the main, been kept at a relatively low wage, black workers at the present time tend to be more militant. They realize that they can no longer move into this preferential treatment that many other members of the working class enjoy; that their wages tend to be depressed; that the gap between the wages of black workers and white workers is widening to the temporary benefit–and I want to underline the word temporary–of the white workers. What happens, for example in the automobile industry, is that black workers have the jobs at the point of production where exploitation is the greatest. But of course there is also a natural development of capitalism. Black workers are now becoming more concentrated in automobile industries. And these industries are very necessary for the maximum profit. So that, in order to build an automobile you have an assembly line of frame builders. An automobile, of course, can never be complete without a frame. In many factories in Detroit, black workers are the majority of frame builders, and it is impossible now for a plant to operate if the black workers of that plant should go on strike.

And because black workers see the political ramifications of this, they tend to challenge those who collaborate with the ruling class, and their consciousness as workers is considerably raised. But it requires the efforts of the whole working class, black and white, united in opposition to the bosses, to raise the total level of consciousness to any large degree. In many industries, rank and file caucuses are now developing with certain advanced forces in their ranks, forces outside the leadership, outside the categories of paid functionaries. These are black and white. There are also black caucuses within the trade union movement. And they are now in the process of challenging the do-nothing approach of George Meany’s AFL-CIO leadership, and the rest of the hierarchy of labor leaders.

In recent times the struggles of the peoples of the Third World and the struggle of the student movement, particularly in the most developed countries, have led some theoreticians to the conclusion that the working class is no longer playing a vanguard role in the struggle for the construction of a new society. The question is whether your analysis of the situation of the working class in the United States today implies this conclusion or whether you simply consider that the American working class is now passing through a stage which might be overcome in the future.

First of all, to imply that the working class is not carrying out its vanguard role is not the same as saying that it does not have that role to play. I don’t feel that the student movement will ever carry through a revolution, for practical reasons if for no others. For example, the students in New York University went on strike against the war in Cambodia. The bosses were able to organize a number of construction workers to oppose the students, and these workers beat the students up. Now, the working class, if not organized against the ruling class, can become a force for reaction and can be made a fascist working class. This is particularly true in an advanced country, a developed country. The working class, if organized, will and can lead the rest of the population. This does not mean that the consciousness of the student movement against oppression does not play an important role in raising the consciousness of the working class; but the working class must assume its role as vanguard. Otherwise, in my opinion, there can be no successful revolution in the United States.

This is proven by those leaders of the black liberation movement who are copied by the bourgeoisie, and become bourgeois themselves. Their role is not to organize masses to resist the advances of capitalism, but to extend the benefits of capitalism to a very minute segment of the black bourgeoisie, still keeping the working class in the position of greater and greater exploitation. And in this case, the exploitation is by blacks as well as whites.

To what extent may the resumption of its vanguard role by the American working class be related to the armed struggle for national liberation which is being waged in the Third World at present–specifically in Africa, Asia and Latin America?

To the extent that this rank and file that I spoke of challenges the politics of the leadership of the trade union movement, and to the extent that it begins to recognize the US as truly an imperialist country, and to realize that it has an affinity with the whole of the working class throughout the world, it will assume its vanguard role. This level of understanding is still in its infancy. Most workers are still concerned with their immediate conditions in the United States.

For example, when the postal workers went on strike, although it was a most militant strike, they were afraid of linking their conditions with the war in Vietnam because they felt that would weaken their bargaining power. So that there is still a hesitancy on the part of the working class to link the struggles of the working class with the world movement or the movement for national liberation.

There has been some attempt to organize the workers to oppose the war in Vietnam. Little by little, it is taking place but it is still very very minor. For example, one of the ways in which this can be achieved is in construction. One of the first things that Nixon did before his Vietnamization speech was to announce a cut back in housing construction in the United States. Naturally, the working class sees that there is a connection between the war and between what is possible in a peace-time economy. But at the same time, unlike other countries, the United States economy just booms during a war, because of the exploitation of other peoples. So there is, again, a temporary benefit. But because that benefit is so temporary, the workers begin to feel it in a number of ways. In the main, in taxation, lack of housing, lack of medical care.

In New York City, to take an important example, reform is no longer possible. You can no longer build enough hospitals, enough housing, enough schools without at the same time ending the war. But if you end the war, there will be more unemployment. In other words, if there are houses, people can’t afford them. So the situation in New York can no longer be viewed as a situation in which limited reforms will work. Radical changes have to take place. And unless there are radical changes, the city will continue losing its ability to take care of its population.

For the working class to assume this vanguard role, means placing the blame for the plight of the people of the United States squarely on capitalism, and identifying its own struggle with that of other peoples.

In reference to the struggles of peoples of the Third World, how does the Communist Party view these armed struggles developing in the continents of Africa. Asia and Latin America against imperialist domination?

Many understood the correct policies of peaceful coexistence between different social systems to mean also coexistence between oppressor and oppressed. This lack of ideological clarity led in some instances to a de facto suggestion that the national liberation movements should not necessarily utilize armed struggle to achieve their freedom. And In addition to that, this incorrect understanding of the theory made it possible to underestimate the importance of the national liberation struggles throughout the Third World, which are absolutely necessary to the defeat of imperialism. I think the world communist movement, including our own Communist Party, has begun to correct its understanding of the theory of peaceful coexistence, I think the Communist Party in the United States understands that the forces for national liberation have the right and the necessity to struggle with arms–and that their continuing struggle has, in itself, increased our understanding of that necessity. The repercussions of that on our own party policy raise new questions as to what our international responsibility is, and how we explain it to our own working class. Within this context, any opportunism on the part of our Party serves to hold back the understanding of our own working class. So that the whole question of armed struggle becomes not only important for an international understanding, but for the raising of consciousness in our own country.

Referring again to the black movement and to the slogan “Black Power," which was used by the most radical organizations, such as the Black Panther Party, who were then accused of splitting the movement with this slogan of “Black Power” and their continuous exhortations to violence for the achievement of their human rights, did the slogan in fact tend to divide rather than unite the black movement?

The cry for "Black Power" did two things: it raised the level of consciousness of black people because it meant, in the first place, that unity of black people was an absolute prerequisite for winning any meaningful changes. But it also meant that all black people had to be organized, and in that sense it was extremely important.

The resistance to the slogan of “Black Power" came from these forces in the general student and liberal movement who felt that black people were asking for too much too fast. Rather than agreeing that the slogan was splitting, I would say that it showed that, even within the progressive movement, whites were not ready to grapple with their own racism. And that they were really afraid to attempt to organize whites, and that they really gave in to the capitalists on the whole question of racism.

The charge of violence has also been made by such people, particularly against the Black Panther Party. Now with respect to the Black Panther Party, the position that any thinking radical would take is that, in the United States, self-defense is a constitutional right, and to deny self-defense to black people is ridiculous. But you cannot very well defend yourself without guns. And in the beginning, the Black Panther Party made the gun the organizing issue and the manifestation of militancy. So instead of having an ideology on which to base a demonstration, or instead of going out to organize around a specific need of black people, they spent a great deal of time talking about the necessity to arm. But in my opinion there were never any appeals for violence on the part of the Black Panther Party. Stokely Carmichael did, however, make such appeals, specifically around the time of the upsurge in Washington, DC. But even this was never really an appeal to take to the streets in armed warfare.

The resolution of the Communist Party in 1969 took the position that black people have not only the right but the duty to defend themselves, their homes and their property by whatever means, including arms; but that the best defense is the organization of masses of black people, specifically the working class, in efforts to resist the advances and the repressive measures of capitalism. And that the role of white–the white working class and especially the Communist Party– is to be at the side of black people in whatever method of struggle.

No appeals to violence as the answer to the problems of oppressed

people can organize these people. It is necessary to arouse the total black community to make their voices and demands known, to indicate forcefully that they will not tolerate the repression and murder of the Black Panther Party and its leadership, or any other leaders of organizations opposed to racist oppression and genocide under US capitalism.

While we view the struggle for black liberation as an absolute necessity for the defeat of US imperialism, we do not see that struggle as one to be conducted by black people alone. Race warfare is not only not the answer but is an empty, defeatist gesture. It means suicide for masses of blacks and temporary victory for capitalism.

A Voice from the Monster: Charlene Mitchell in Tricontinental (Theoretical organ of the Executive Secretary of the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America), No. 23 (March-April 1971), pages 121-. This issue of Tricontinental is available via The Freedom Archives, “a non-profit educational archive located in Berkeley, California dedicated to the preservation and dissemination of historical audio, video, and print materials documenting progressive movements and culture from the 1960s to the 1990s.”