In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Habiba Ibrahim. Ibrahim is Associate Professor of English at the University of Washington. Her book is Black Age: Oceanic Lifespans and the Time of Black Life.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Habiba Ibrahim: The current climate raises questions about what it means to be Black and situated in this particular moment in time. Is this progress? Are we regressing, or is there no clear schema to describe the direction of time’s unfolding at present? The conflicts and challenges of any given moment has the potential to reveal some new evidence of things not seen; Black Age is one exploration of how new insight emerges through the events of disorienting times.

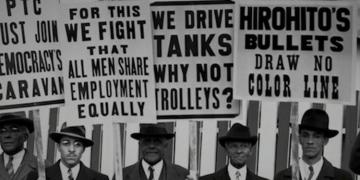

It began with an awareness of something familiar. After George Zimmerman killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2012, a common observation abounded: in dominant culture, Black children are often not perceived to be children. They are routinely seen as adultlike and subject to the punitive treatment of adults, but never granted the privileges of adulthood. The killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice made the social and political significance of age conspicuous. Somehow, at the location of Black embodiment, “age” is unrecognizable, invisible, malleable, or insignificant. Throughout the 2010s—an extended moment of crisis for Black lives and U.S. democracy in general—the conspicuousness of age broke through the surface of what we already know about anti-Black racism: age is a key factor of the Black body’s racialization. In the Western modern world, blackness is what I call “untimely,” and this untimeliness is expressed through and as “age.” Through the various phases of transatlantic slavery, blackness had been dispossessed of time on various scales, from bodies to histories. Blackness, having been violently emptied of normative meanings of time, could appear to be any age at all—or to lack age entirely.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

There are ramifications for how we understand anti-Blackness and responses to it in the present moment. Black children and adults across genders have suffered the abuses of being made untimely. When Black embodiment is the screen for fantasies and fears of the dominant culture, “age” becomes a technology of domination. Children are adultified, adults are infantilized, and both transformations justify abuses of various kinds, like pushing children out of schools and into carceral spaces, and presuming that adults are professionally unfit or socially incompetent. Although specific forms of abuse may transform overtime, abuse of untimely Black bodies in general stems from a long history of how blackness has been constituted through the processes and reasoning of racial capitalism. However, resistance is also a part of this long history. Untimeliness is not just the outcome of abuse but also a site of social reclamation. (Just consider: “Black don’t crack.”) Black age is a lens through which to examine how embodied time is the scene of constant struggle.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

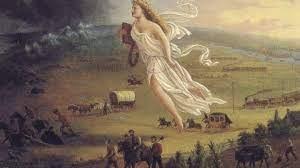

My hope is that Black Age breaks the ideological associations we make between “development” and “hierarchy.” These associations seem so natural because Western modern ways of knowing have baked them into nature itself. Developmental time—evolutionary, biological, civilizational, historical time, the time that leads to the apex of Man—is hierarchical. In it, some people reach the highest level of human existence while others, the supposedly least developed, the “primitive,” are relegated to the lowest rungs of subhuman or nonhuman existence. The ideological binding together of developmental time and hierarchical social relations serve the needs of racial capitalism, and it is commonplace to observe that colonial conquest entailed subordinating the colonialized to the status of children, since proper adulthood existed elsewhere, in metropoles. Similarly, the so-called infantilization of enslaved adults has social resonance long after slavery, as when Black men are inappropriately referred to as “boys” and Black adults across genders are denied the honorifics of seniority.

Time never stands still. De-naturalizing the link between developmental time and hierarchy enables us to see how this link was historically constituted, how it functions throughout time, and how ideology transforms as culture transforms. “Patriarchal adulthood” is the term I apply to the subject who makes a claim to all manners of developmental superiority in relation to others. This occurs in a variety of social and institutional contexts: in liberation movements, electoral politics, and the university, to name a few examples. In an ideological sense, “adults” and “children” are relational positions that reveal something about how power is claimed, conferred, or denied at any given moment.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

Black feminist literary and cultural critics of the 1980s and ‘90s developed groundbreaking vocabularies and paradigms that continue to influence our thinking. I’m interested in the conditions under which they did their work at the time—when continental “theory” loomed large and absorbed much of the air. Black feminist scholars thought theoretically with the use of other cultural and intellectual tools. Or, as Hortense Spillers has done, they used poststructuralist devices to build a doorway that led to an entirely unthought-of vestibule from which to comprehend the making of the “New World.” In our own time, we know that the academy governs the work of knowledge production with value judgments based on scholarly trends and disciplinary laws. 40 years ago, Black feminist reading practices blossomed while Black women’s literary work found larger audiences, both in the academy and the mainstream. So what might it have felt like to be at the vanguard of Black literary studies and yet to receive the message that one’s scholarly methods and interests were not sufficiently “scholarly”? Did being disciplined in the academy this way—being both ahead of the curve in terms of field development and yet supposedly behind in the grand “race for theory”—lead to a peculiar sense of time? In my book, I consider these questions in terms of age.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

What if we imagine an untimely world in which sociality is based on non-exclusionary, non-hierarchical ethics of relation? Adulthood would be disentangled from patriarchy, and “maturity” would find its new definition in the value of mutual protection. The expansion of protection is at the heart of this book’s liberating potential. For all of us to be deemed worthy of it, we would have to dismantle the ideological trappings of innocence and its counterpart, developmental superiority; both have a history of being racially and socially exclusionary. To quote Audre Lorde as I do in the book, in an untimely world we would commit to “patterns for relating across our human differences as equals” (“Age, Race, Class, and Sex”). No more and no less.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.