"This episode of Black Republic Media is the second in a series entitled, Murder Inc: The White Settler Republic as Homicidal Maniac. In this episode, Violence is Their Religion: How Murder Gives the White Settler Purpose, we break the silence surrounding the 400-year-old serial killer known as settler colonialism in the hopes of lessening the Devil’s power over us, by giving him, at long last, a name."

Originally published in Black Republic Media.

Twenty-four years ago, I moved to Johannesburg to head the Washington Post’s Southern Africa Bureau. The Post’s home office was located in the city’s tony northern suburbs, which was reserved for whites during apartheid. Voters of all races went to the polls for the first time in 1994– five years before I arrived–to abolish white minority rule.

But you cannot undo in half a decade a white settler crime spree that has terrorized Black people the world over for half a millenium, as I discovered the hard way while jogging through my suburban Johannesburg neighborhood one spring afternoon.

Suddenly, as I ran past a row of gated, walled-off rambler-styled homes, I heard barking ; I turned sharply to my right and saw a dog–maybe a labrador retriever– clearly with bad intentions, running towards me.

I froze, remembering that someone had once told me that dogs return our energy. But this dog apparently had not gotten the memo, crossing the busy four- lane thoroughfare into traffic, and continuing to bear down on me.

Finally, in desperation, I turned to my left, spied a six-foot- tall- security wall, and leapt. The dog continued barking at me for what seemed an eternity before the electric gate across the street opened, and he ambled home. When the path was clear, I rappelled down the wall, and continued on my way.

A few days later I went jogging again, but as I approached Cujo’s home, I spotted a white couple jogging towards me. When I asked if they had encountered a dog in the vicinity of my canine tormentor, they responded “no,” and I sped off, relieved.

Not two blocks later, the same dog was nipping at my heels. I hadn’t heard him bark, and by the time I spotted him he was in a full trot. There was no time to do anything but run. I took off, zig-zagging through the neighborhood for another two blocks. Finally, as he closed in for the attack, I leapt again onto a security wall, slicing a gash in my calf so deep that the scar remains visible to this day.

I recounted the incident months later to some South African friends, both Black and white, and they explained to me that this reflected one of the more perverse legacies of apartheid, which was created in 1948 to address white South Africans concerns that they being replaced by the African majority.

Whites often trained dogs to protect homes and businesses by attacking Blacks, and only blacks. In other words, that dog who twice chased me up a wall had a Pavlovian response to my dark skin and reflexively chose violence to eliminate the threat; yet the same dog had spotted the white couple in the same spot and engaged in the same activity only a few minutes earlier, and he didn’t even budge.

One anecdote sums it up: there existed during apartheid a company that employed just a single Black employee, whose job description included running the length of the property every so often to ensure that the guard dogs would chase after him.

And here is the piece de resistance, as I was told; once a dog is trained to attack a specific racial category, he cannot be reprogrammed or retrained to “unsee” what he once saw in the menacing Black body. And if the choice was between putting down a pet, or some innocent kafir getting bit, well, you already know the value that white folks attach to their dogs.

I was reminded of my ordeal with the mad dogs of South Africa while watching the video of a white, former U.S. marine strangling to death an African American man, Jordan Neely, on the F train in New York City. A 30-year-old homeless man, Neely, by all accounts, was loud and “aggressive” in voicing his frustration to the other passengers on the subway but hardly posed an imminent threat. I am familiar with that F train and during my time in New York, it was not uncommon for the homeless to board at the stop in the SOHO neighborhood to dance, sing, or just plead for handouts. Occasionally, influenced either by alcohol or simply the frustration of living hand-to-mouth, a homeless man might be belligerent, or loud, or particularly persistent.

But I never, ever ever, saw a homeless person threaten a passenger on the train, let alone assault one.

So the first question is why did the white man, reportedly an ex-U.S. marine, see fit to choke Neely–by all outward appearances a slightly-built man–for 15 minutes causing his death?

And that is really the central question of American life, isn’t it? Why does the white settler–or the chicken-and-butter-biscuit-eating Negroes in his employ–brutalize one African American after another for the most trivial reasons? Our streets run red with the blood of so many Black bodies that it becomes a blur, like melting corpses piled high atop a funeral pyre.

Last month, there was the 85-year-old white man in Kansas City who shot a Black Kansas City teenager, Ralph Yarl, in the head, simply for knocking on his door; the month before that was Irv Otieno, who died of asphyxiation after seven Virginia sheriff’s deputies and three hospital orderlies knelt on his chest for 12 minutes; in January, it was the five Black Memphis police officers who gleefully beat Tryee Nichols to death in January, in their morbid reenactment of the five, white, Los Angeles police officers who wailed on Rodney King 31 years ago.

On and on it goes, from Emmet Till to Botham Jean, Fred Hampton to Michael Brown, Little Bobby Hutton to Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner to George Floyd to Sandra Bland.

The technological changes are stunning, and the race of the lynchers may differ from one circumstance to the next but the race of the victim (Black) the motivation (white supremacy) and the result (death or grievous injury) remains the same as it ever was, which raises a second, and perhaps far more profound question:

Can America’s racist white killers be rehabilitated any more than South Africa’s racist dogs?

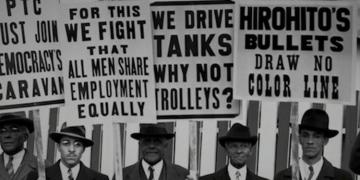

Something the late African American scholar Otis Madison was fond of saying certainly suggests that the European settler in the U.S. is brainwashed, similar to the South African attack dogs: “The purpose of racism, ”Madison asserted, “is to control the behavior of white people, not black people. For blacks, guns and tanks are sufficient.”

Madison’s implication is that racism is nothing more than a particular narrative–albeit one that is antithetical to truth, bereft of all logic, and a disfigurement of our humanity –intended to produce a kneejerk response in white folks similar to the dog that chased me outside Johannesburg more than 20 years ago. In that context, anti-Black violence can best be understood as a tactic deployed by the ruling class to discourage Black resistance, and maintain the status quo by pitting their whites employees against their Black employees.

What better way to distract the knavish mob and prevent it from storming the Bastille than by exhorting the unwashed to fight among themselves?

You needn’t be a revolutionary to see that the United States is going to hell in a handbasket. And while it’s true that statistics–from household debt to the minimum wage to inflation to rising global temperatures to the alarming number of hate crimes or deaths in police custody–help explain Americans’ dystopia, our collective dark night of the soul is, at base, a crisis of storytelling which is the predicate for Neely’s lynching aboard a Gotham subway last week.

Think about it for a second: the stories we most remember–whether in the Godfather franchise or the New York Times magazine, your cousin’s eulogy for your favorite uncle or the novel you just could not put down–has a beginning, a middle and an end, is peopled with colorful characters, and uses language as a sculptor would a hammer, smashing rock-hard myths to reveal us as we truly are, in ways that are often surprising and even unsettling. The best stories, in other words, are authentic, gritty, true-to-life, like the Blues, or Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger in In the Heat of the Night.

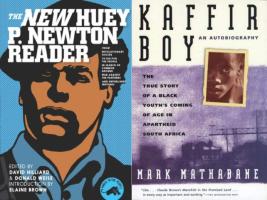

Malcolm X, you may recall, began his career with the Nation of Islam as a journalist, pioneering Muhammad Speaks; similarly, Ida B. Wells was a storyteller, as was Fannie Lou Hamer, Kwame Ture, Paul Robeson, Marvin Gaye, Biggie, Richard Pryor, Fidel Castro, Steve Biko, Dave Chappelle, and every icon of African and diasporic liberation movements who articulated, in plain proletarian English, our freedom dreams, unbound by the contemptuous white gaze.

In opening her son’s casket, Mamie Till was a raconteur of the first order; it was her grief, and grace that inspired Bernardine Dohrn to join white revolutionary Leftists who collaborated with the radical Black Power movement of the 1960s and 70s.

The stories that we most often tell each other today, both through our news and entertainment media, and the Academy, conceal rather than reveal, and don’t surprise us so much as anesthetize us with pat, bloodless, poetless narratives that fail to account for the despair, or the anger, or the evil that stalks us. Narratives that valorize the European settler and his colonial institutions cannot solve problems that they, in fact, create, by centering “whiteness,” and subjugating the darker peoples of the earth.

The source of white people’s authority over Black people, Toni Morrison once said, is their power to narrate the world. It is, by and large, the European settlers’ monopolization of the American story, their custodianship of our historical memory, that is the germ of Black suffering, Black dispossession and Black death such as that suffered by the young Mr. Otieno, or Tyree Nichols, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, Amadou Diallo, Tamir Rice, Laquan McDonald, and on an on it goes here in America’s killing fields.

More than 30 years ago I was a City Hall reporter for the Detroit Free Press. At one city council meeting, a Department of Public Works engineer updated the council members on a longstanding problem. Since the 1950s, the affluent, mostly white suburb of Grosse Pointe had leased sewage lines from the city of Detroit. Heavy rains, however, caused the pipes to overflow, and saturated the backyards on Detroit’s east side with the shit and piss from Grosse Point.

The city’s engineer was droning on and on about what was being done to address the problem which had, at that point, been ongoing for nearly 40 years. Suddenly, a councilman named Gil Hill–who you may remember as Eddie Murphy’s profane supervisor in the Beverly Hills Cop franchise–exploded:

“Man, just get it done! Can you imagine how fast they would’ve fixed the problem if the shit was flowing the other way?”

You could’ve heard the proverbial gnat pissing on cotton in Georgia as everyone in the room contemplated the wife of some Grosse Pointe auto executive–that is to say “white”– scraping Black people’s shit off their house slippers after tiptoeing through the backyard tulips one spring morning; in that scenario, everyone understood that white people awash in Black people’s shit is the equivalent of a five-alarm fire.

In his classic book, The Open Veins of Latin America, Eduardo Galleano quotes indigenous, Bolivian rebels who acknowledged their failure to confront the European settler narrative that had enslaved them:

“We have maintained a silence closely resembling stupidity.”

A former foreign correspondent for the Washington Post, Jon Jeter is the author of Flat Broke in the Free Market: How Globalization Fleeced Working People and the co-author of A Day Late and a Dollar Short: Dark Days and Bright Nights in Obama's Postracial America. His work can be found on Patreon as well as Black Republic Media.