“Police can call you a gang member because they observed you with other gang members, who they declared gang members because they were with other gang members.”

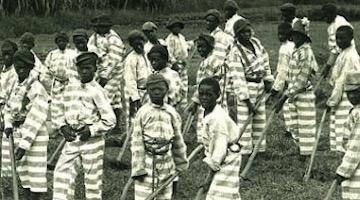

“The Gang database fuels the surveillance, and sometimes deadly policing, of poor Black and Latino communities.”

In August 2016, an administrator for Washington, D.C.’s, Metropolitan Police Department emailed a link to a news article to a colleague in the department’s Criminal Intelligence Branch. The article was about an audit of California’s statewide database of gang members; the database, the audit found, was riddled with civil rights violations and errors, including 42 instances in which the supposed gang member’s age when they were added was less than 1 year old. The article “raised a lot of interesting issues,” the administrator said.

The link was eventually forwarded to Daniel Hall, the intelligence branch’s top civilian analyst. Hall, a main developer of the MPD’s own gang database, laughed off the administrator’s concerns. “See this is why I built the gang database!! Im the savior of this unit!” he emailed a colleague. “As long as you don’t have any one year olds in there,” the colleague replied, adding a winking face emoticon.

“Haha no I created it after I went through all the records,” Hall said. “Im the reallllllll deallllll.”

Yet the gang database Hall helped build suffered from many of the same deficiencies as the California database. A spreadsheet of the MPD database shared internally the next month included a supposed gang member who was less than 1 year old, as well as 2, 3, 5, and 6-year-olds. The 2,575 names in the spreadsheet also included children as young as 14.

“A spreadsheet of the MPD database included a supposed gang member who was less than 1 year old, as well as 2, 3, 5, and 6-year-olds.”

The email chain and spreadsheet are part of a trove of over 70,000 emails and their attachments, sent and received by Hall between 2009 and 2017 and stolen from the MPD as part of a hack by a ransomware group known as Babuk, which claimed to have downloaded 250 gigabytes of data in total. The documents were published last month by Distributed Denial of Secrets, the transparency collective behind BlueLeaks and other recent high-profile document dumps, and made searchable by the Lucy Parsons Labs, a Chicago-based collaborative. The MPD acknowledged an “unauthorized access incident” in late April, and in mid-May, the department sought public help in identifying a man for his “reposting of MPD’s illegally accessed data on social media.” Neither the MPD nor Hall responded to The Intercept’s list of questions.

Other documents from the trove, reviewed by The Intercept, show how the MPD identifies supposed gang members by using hazy criteria typical of other gang databases in the United States and how the department pushes officers to frequently add names to the database. The emails also reveal that the MPD shares information from the database — including full spreadsheets of its contents — with outside agencies and larger regional gang databases and that the department uses it to inform its aggressive policing initiatives.

Gang databases across the country have come under heavy scrutiny in recent years amid revelations of widespread errors, racial profiling, the inclusion of children, their use in immigration enforcement, and other civil rights violations. Police departments, meanwhile, have been tight-lipped about how they develop and use gang databases, refusing to inform people if they’re included, let alone how they were added or how they might appeal their inclusion.

“The emails reveal that the MPD shares information from the database with outside agencies and larger regional gang databases.”

The MPD emails provide one of the least-filtered and most in-depth pictures yet of a local gang database’s operations and flaws — and how it fuels the surveillance, and sometimes deadly policing, of poor Black and Latino communities.

In a statement emailed to The Intercept, the Stop Police Terror Project DC, an organization that advocates for alternatives to policing, pointed to the case of Deon Kay, an 18-year-old whom an MPD officer chased down and fatally shot in September 2020 as he threw away a gun he was carrying. Part of the MPD’s justification for the pursuit was that Kay was a “validated gang member.”

“It’s clear that the entire goal of the gang database is to make it easier to harass and arrest Black people in D.C.,” the group said.

The NOD first established its internal gang database in 2009, giving a variety of officers the power to submit names to the intelligence branch to “validate” and add to the database. The database expanded substantially after February 2014, when the department moved it from an internal drive to a more user-friendly web-based program.

The criteria for “validation,” listed in a 2009 order from the then-police chief as well as hacked emails and attachments, are nebulous. Officers can add a gang member if they have a “reasonable suspicion” that the person checks two of seven boxes, including “associating” with validated gang members, being identified as a gang member by an “unproven informant,” and having been “arrested in a gang area for an offense that is part of the gang’s criminal enterprise.” Officers can forgo the two-criteria requirement if someone “credibly admits” to being in a gang — a workaround other departments have been shown to falsify or abuse — or if a “reliable informant” pegs them as a gang member. The MPD did not respond to The Intercept’s request for definitions of “unproven” and “reliable” informants.

“It’s clear that the entire goal of the gang database is to make it easier to harass and arrest Black people in D.C.”

The MPD also has a second, even looser category of person who can be entered into the gang database: the “gang associate,” whom officers can add if they have reasonable suspicion that they meet just one of the seven criteria.

The criteria represent an “ouroboros of systemic racism,” said the Stop Police Terror Project DC, referencing the ancient symbol of a circular serpent that perpetually devours its own tail. Police “can call you a gang member because [they] observed you with other gang members, who [they] declared gang members because they were with other gang members.”

Indeed, the MPD documents provide ample evidence that officers used social gatherings as a basis for identifying supposed gang members. In several emails, officers requested that new “crews” be added to the database, referring to them by seemingly made-up names, such as street intersections. “Hey dan can you add a crew on the gang database, just put it in as ‘[cross-streets] Crew,’” one officer wrote in July 2014. In the September 2016 spreadsheet of the gang database, around 20 of the more than 100 crew names listed were names of intersections, while more than 50 were names of other geographical landmarks — streets, neighborhoods, parks, and public housing and apartment complexes. These references were sometimes repetitive.

According to Babe Howell, a professor at the City University of New York School of Law and an expert on gang policing, the MPD’s choice to call the groups “crews” is especially telling. “We’re dealing with informal neighborhood peer groups,” she said. The police are “calling them ‘crews’ and certifying them as ‘gangs’ and making them persons of interest, and then … stopping them and arresting them. And there’s so much that’s dangerous about that.”

Federal law requires police to review gang database entries at least every five years, a process meant to help determine that “the subject continues to be reasonably suspected” of being in a gang. Yet the emails show that the MPD reconfirmed crew members based on exceedingly tenuous criteria and failed to delete database entries regarding crews that had already been disbanded.

“The police are “calling informal neighborhood peer groups ‘crews’ and certifying them as ‘gangs.’”

In October 2013, Hall compiled a list of gang database entries that were going to hit the five-year mark. In response, a captain instructed officersto keep the entries in the database simply “if they have been arrested in the gang area in the past 5 years.”

A year later, in September 2014, 13 members of another crew came up for their five-year revalidation. In an email, an officer explained that the crew needed to be removed from the gang database. “It is no longer a gang/crew. Members of it have gone to other crews and should be validated accordingly,” the officer explained. Six days later, Hall said the crew had been removed from the database. Yet eight days after that, the crew was listed among that week’s “arrests of validated crew members.” The crew was also included in the September 2016 spreadsheet of the gang database. And an email from September 2017 shows the supposedly defunct crew among a list of MPD-validated gangs.

At the same time, emails show MPD higher-ups pushing for more additions to the database. In December 2016, the Criminal Intelligence Branch started keeping track of how many gang members each officer submitted and sharing them with relevant officers and staff on a weekly basis. In response to one of the weekly updates, a lieutenant replied to the email chain to congratulate two officers who had validated double-digit gang members or associates that week (compared to other officers each validating three or less), as well as an officer who submitted several gang intelligence reports.

“For you back markers out there,” the lieutenant wrote, “let’s see if we can bring these numbers up.”

The MPD has used its gang database to fuel tough-on-crime policing initiatives. Since 2010, the MPD has conducted an annual “Summer Crime Prevention Initiative” to “eliminate violent crime” and “hold repeat offenders accountable” in crime-dense areas of the city. According to the hacked emails, the initiative has relied partly on gang database intelligence.

“Emails show MPD higher-ups pushing for more additions to the database.”

Each spring, the emails show, the MPD designated areas to receive the brunt of the increased police presence — almost exclusively in D.C.’s largely Black 5th, 6th, and 7th police districts — which the intelligence branch overlayed with maps of “crew areas.” The intelligence branch then compiled lists of “SCI POIs,” or Summer Crime Initiative persons of interest: people in the designated areas who are in the gang database and/or have criminal records. The lists were stored in the gang database portion of the department’s internal shared drives. As the MPD conducted its summer crackdown, it kept track of how many SCI POIs it was able to apprehend for any charge, violent or otherwise.

In 2015, the office of the chief of police also ordered the intelligence branch to compile lists of “about 10 criminally associated families” in each designated area, which were also kept in the gang database drive. (The quota was later upped to 15 families, prompting the intelligence branch to ask school police officers for leads.) The branch distributed initial lists, complete with mugshots, among officers in April and May of that year; all of the 30 families included were Black.

August 2017 documents show that of the 83 persons of interest arrested during that summer initiative, around half were arrested primarily for minor offenses like fare evasion, drug crimes, probation violations, bench warrants, and absconding from custody orders. Roughly one-third of the SCI POI arrests that year came from D.C.’s transit police, according to an email.

According to Howell, such aggressive gang policing creates a “self-fulfilling prophecy” — one in which, like stop-and-frisk policing, cops are given rein to “put a label” on young Black and brown people and then use that label as an excuse to “police the hell out of” them.

“It’s racism that has enough of a mythology behind it,” Howell said. Police “believe that the 14-year-old that they’re adding to that gang database — it’s only a matter of time until that kid is going to commit a violent crime.”

“The chief of police ordered the intelligence branch to compile lists of “about 10 criminally associated families” in each designated area.”

In addition to the MPD’s own initiatives, documents reveal that at least a dozen outside agencies and law enforcement information-sharing projects have used data from the MPD’s gang database in their own policing efforts, including the D.C. court supervision agency; the FBI; the Secret Service; the Marshals Service; Homeland Security Investigations; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; the Marine Corps; and a law enforcement agency collaboration known as the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area.

Through the MPD’s involvement in the Maryland Coordination and Analysis Center — one of the post-9/11 intelligence-sharing partnerships between local, state, and federal law enforcement known as fusion centers — the gang database spreadsheet was ultimately posted to an information-sharing system that is currently accessible to more than 9,400 law enforcement agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security, which houses Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Being added to the gang database can have serious immigration consequences. In 2017, for example, ICE detained an undocumented recipient of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, status in D.C. and accused him of being in a gang, which would nullify his DACA protections and allow the agency to deport him. But he was never part of a gang, according to his attorney, Julie Mao, deputy director of Just Futures Law, an immigrant rights law firm. Eventually, a judge released him from detention, and Mao filed a public records request to determine how her client got pegged as being involved with a gang. The request yielded an MPD gang validation form, which claimed that when he was a minor, he “self-admitted membership” in a well-known gang to a school police officer. (The Intercept reviewed a version of the form that Mao had redacted to conceal identifying information.)

These types of encounters have long made Black and brown youth in the city fearful of gang policing. “They say, ‘Oftentimes I’m just fearful of being out in public, remaining in one place and talking to people. I’m afraid to hug someone or shake someone’s hand,’” said Mao, who has sued the Chicago Police Department over its gang database practices and now represents immigrants in some of D.C.’s most aggressively policed communities. “Because in high-traffic areas, cops are often sitting all day in their cars, looking and surveilling.”

Membership in the gang database can also spell disaster for those involved in the criminal system. In D.C., gang-related charges come with up to 10 extra years of prison time and, potentially, incarceration at a higher-security facility. Law enforcement uses the threat of gang sentencing to its advantage, including as a coercive tool during interrogation. In November 2014, a detective with the U.S. Park Police emailed Hall to check if a robbery suspect was included the MPD database.

“Just trying to see if we’ll be able to try and get enhanced charge since they’re [sic] was a group of suspects but he’s the only one caught,” the detective wrote.

The suspect wasn’t in the database. “That would have been great to get that enhanced charge,” replied Hall, “that’s a nice tool at your disposal.”

Chris Gelardi is a New York City-based journalist.

This article previously appeared in The Intercept.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com