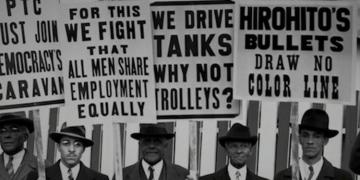

The author examines how ordinary workers in multiracial societies simultaneously challenged racism and their bosses.

“Black workers proved powerful enough to close down South Africa’s gateway to the global economy.”

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Peter Cole. Cole is Professor of History at Western Illinois University and a Research Associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute (SWOP), University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. His book is Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Peter Cole: It may seem that life in America and the world are crazy now—and they are—but it’s not the first time. Much of my book explores earlier, chaotic times when dockworkers, organized in unions and outside of them, acted as the tip of the spear in the fight for radical social change. For instance, in late 1972, the all-black dockers, mostly Zulus along with some Pondos, downed tools and walked off the waterfront in Durban, the busiest port in South Africa and all of sub-Saharan Africa. Though desperately poor, their strike wasn’t solely for wage hikes. Black workers, organized, proved powerful enough to close down South Africa’s gateway to the global economy! Ipso facto, that also was an attack on the entire apartheid system. And everyone knew it. Six weeks later, other black workers struck, launching the Durban Strikes of 1973. 100,000 black and Indian workers striking shook white supremacists to their core.

Similarly, in 1949 in San Francisco, the busiest port on America’s West Coast, longshoremen belonged to Local 10, the largest and most important branch of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU). The ILWU was one of the “left-led” unions born in the fires of the 1930s that came out of World War II fighting for civil rights but whipsawed in a nation gripped by a Red Scare. In that moment, Local 10’s membership—largely white—voted to not expel their most inexperienced members despite a slowing economy. That is, Local 10’s members voted to work less (which is to say, suffer more), together, rather than kick out the thousand or so African Americans who had entered the local when work was flush during the war.

In these two examples, and many others, my book examines how ordinary workers in multiracial societies simultaneously challenged racism and their bosses.How could they not? They lived in countries dominated by racial capitalism, as we still do. These issues are as relevant now, as then.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

Well, even though my book is a few hundred pages and heavily researched, the title gives the game away: Dockworkers have power. That’s it. Now, I wouldn’t say dockworkers are the only workers who have power but I am mindful that they—and others working throughout the transportation industry—do have a particular power as they stand at a choke point of global capitalism.

Lou Goldblatt, Harry Bridges’ right-hand man in the ILWU for forty years, said as much in one interview: “The shipping industry has a feature that should never be underestimated—the economic power of the longshoremen is fantastic compared to most workers; the amount of economic leverage they have.”

Many would extend Goldblatt’s claim to all shipping, to rail and truck, to what is called the logistics industry or supply-chain. I agree with that. In other words, activists—in every country, worldwide—should be doing as much as they can to build where we already possess some strength. When your group supports a local union effort, they’ll support yours, too.

“The economic power of the longshoremen is fantastic compared to most workers.”

I think that the example of Local 10’s decades of anti-apartheid activismis another good example of how community activists can learn from and coordinate with unions to advance social justice. In 1984 (and a few times previously), Local 10 members refused to unload cargo from South Africa to protest apartheid. Thousands of people from the community, including union school teachers, rallied in solidarity. A few months later, University of California-Berkeley students stepped up their efforts to get the UC system to divest from South Africa. My favorite photo from the Cal protests is of the ILWU banner, “an injury to one is an injury to all” amidst a sea of student protesters.

These examples are lessons, obviously, but they’re also inspirational. We need victories, however small, because no one joins a revolution that hasn’t happened yet. It’s too risky and uncertain. One needs to build a movement, from the ground up, with incremental gains, growing labor and other social movements. That way, we’re ready for when the bigger opportunities appear. And they will.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

In the Time of Trump, there has been plenty of bashing of so-called white working-class men and women. As if, thanks to some poor and working-class white folks in rural Michigan, we’re all stuck with Trump. I can’t deny that there are some racist white people in the working class—any is too many. But we need to fix our gaze, firmly, on those with the real power—the ruling class, the rich and corporations! Truthfully, the average Trump voter earns more than the national median income. Sure, some Trump voters are white working-class people. I know, I live in rural west-central Illinois where the closest “big” city is St. Louis, a 3-hour drive. That said, the narrative blaming these white folks is as elitist as it is divisive. I think it far wiser to focus on those with power—elite white men, like Trump himself!

And, guess what, some working-class white folks are anti-racist. Some belong to the ILWU and not just in Local 10. The ILWU takes principled stands against racism. Local 10, in particular, walks at the forefront of the struggle against white supremacy, historically and during the last twenty years. For instance, in 1999, Local 10, led by rank-and-file white militants Jack Heyman and Howard Keylor, convinced the coastwide Longshore Caucus to “stop work” to protest the racist persecution of black journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal. As a result, they shut down the entire West Coast for an entire 8-hour day shift! That day, Local 10 members also led a march of 25,000 strong in San Francisco. On May Day in 2015, Local 10 stopped work for a shift to protest racist police brutality—in the Bay Area and across the country in North Charleston, South Carolina. In August 2017, they were at the center of Bay Area-wide counter-protestswhen white nationalists declared they intended to rally in San Francisco. Are these actions somewhat exceptional? No doubt. But the point is that abandoning the entire white working-class to Trump is hardly a wise strategy.Organizing multiracial unions, my book suggests, is quite possible and should not be abandoned by those who style themselves as leftists.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

Well, the first was a certifiable “working-class hero,” to use John Lennon’s phrase, Herb Mills. Hands down, the best part of researching my book was getting to meet some amazing Bay Area dockworkers. One of those was Herb. After WWII, Mills was working at the legendary Ford River Rouge factory, outside Detroit, having dropped out of high school, when some Communist fellow workers encouraged him to go to college. He ended up graduating Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Michigan, went into the Army, entered a PhD program at Berkeley on the GI Bill, helped form the graduate student organization called SLATE that led the anti-McCarthyite protests at the HUAC hearing in San Francisco, dropped out of grad school when he got into Local 10, later got permission to leave the waterfront to finish his dissertation (from Irvine), graduated and went right back into the union! Almost immediately, he was elected to Local 10 office and helped lead the longest strike in US maritime history (in 1971-72). All the while he wrote insightful essays analyzing his union and industry. He just passed away a few months ago. Herb Mills, presente!

I’ve also taken inspiration from the Syrian intellectual, Yassin Al Haj Saleh, “the conscience of the Syrian revolution.” I even got to cook him his first veggie stir-fry with tofu (in some spicy Turkish biber salçasi). My partner and I were living in Istanbul during our sabbaticals in the winter of 2015-16. I was writing my book in a flat with a view of the Bosphorus, containerships passing by, while she conducted interviews for her incredible oral history of the revolution. She introduced me to Yassin. Meeting someone who has risked his life—and been tortured in prison—and still is willing to stand up against injustice. Well, it puts everything in perspective.

I never met Steve Bikoand he doesn’t play much of a role in my book, but if there was an amazing leader in Durban in the early 1970s, it was the “father” of the Black Consciousness Movement. I just wish he had lined up with some dockers.

Closer to home, I remain deeply impressed by scholar-activists, one foot in both worlds, who work with people across generational divides to boot. Folks like Barbara Ransby and Martha Biondi, Keisha Blain and Marcus Rediker.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

I appreciate this question as a lover of science fiction. While these days we can’t get enough of the dystopias, my love of scifi is because I continue to believe another, better world is possible. I choose hope because the alternative, to me, is a nihilistic road to nowhere. That’s why I, like so many others, love Star Trek in its many iterations.

So, too, my book (now there’s a segue)! Unions have become so weak, in the United States and other countries, that many Americans don’t even know someone in a union. Let alone that many unionists fought against white supremacy and for socialism. When the ILWU was born out of the fires of 1934’s legendary Big Strike, which briefly morphed into the San Francisco General Strike, the longshoremen proceeded to undertake some truly radical initiatives.

For decades, centuries, dockworkers had suffered from an incredibly abusive hiring system, the shape-up; it was ripe with exploitation, bosses played favorites and demanded bribes. Once the workers built a strong union, they eliminated this oppressive system and instituted another one, both democratic and egalitarian. When shippers needed workers, they called the union hall. Job dispatchers, members of the union and elected annually by their fellow workers, distributed jobs via a “low man out system.” The worker who had worked the least in the previous quarter year received first chance at a job when showing up at the hall. The last shall be first—but in action. You might call that Christianity. You might call that Socialism. Not only is another world possible, humans have given us glimpses of it already.

I should say that I’ve been told that I sometimes romanticize my subjects. I don’t mean to. The people I study had plenty of warts. But I’m quite comfortable with researching and writing about subjects that I share some sympathies with and respect of because life’s too short. I try to write what some call a “useable past.” Howard Zinn said, “You can’t be neutral on a moving train.” True that.

Roberto Sirvent is Professor of Political and Social Ethics at Hope International University in Fullerton, CA. He also serves as the Outreach and Mentoring Coordinator for thePolitical Theology Network. He is co-author, with fellow BAR contributor Danny Haiphong, of the new book, American Exceptionalism and American Innocence: A People’s History of Fake News—From the Revolutionary War to the War on Terror.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com