A 1930 speech by Black anarchist and labor organizer, Lucy Parsons, recalls the radical origins of May Day.

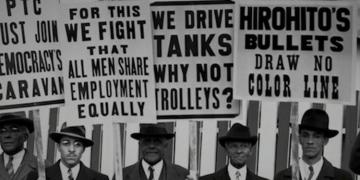

On May 1, 1930, as global capitalism convulsed and shuddered through an unprecedented crisis that appeared to presage its inevitable collapse, twenty-five-thousand workers braved police terror and sedition charges and gathered for a May Day rally at Chicago’s Union Park. The workers marched to City Hall, where a “committee of the unemployed,” presented demands for “work or wages” to the mayor and city council demands. They then strode to the Ashland Boulevard Auditorium for a mass meeting. The meeting opened with a spirited rendition of “The International,” the anthem of the international workers movement, before the audience heard a number of addresses – including one from a figure the chairperson described as “one of the old pioneers in the fight for the eight hour day,” Lucy E. Parsons.

Both the May Day demonstration’s location in Chicago and the inclusion of Parsons on the mass meeting’s stage were of historical and political significance. Not only were the origins of May Day in the events that occurred in Chicago forty-four years earlier, but Parsons herself was a participant. Labor unions had called for a general strike on May 1, 1886 to demand an eight-hour day. Across the United States, nearly half a million workers joined the strike. Chicago was the epicenter of the movement, with perhaps 100,000 workers and their supporters and allies taking to the streets. Two days later, police broke up a peaceful strike at the McCormick Harvesting Company, killing one worker and injuring many others.

On May 4, a rally at Haymarket Square was organized to support the McCormick workers and to protest the police. A bomb was thrown into the crowd and in the ensuing chaos, seven cops and four workers were killed, mainly by gunfire. While most people believed the police were responsible for the bombing and the shootings, the incident was used by the state to attack labor radicals. The Chicago police arrested and raided the homes and offices of suspected anarchists. Eight anarchists, including Lucy Parsons’ husband, Albert, who had spoken at the Haymarket rally, went on trial. All were found guilty of conspiracy and four, including Albert Parsons, were executed on 11 November 1887, hung in the gallows erected behind the Cook County Courthouse. The roots of May Day – or International Workers’ Day– are in the efforts to commemorate the 1886 general strike, the so-called Haymarket affair, and the death of Parsons and the other Haymarket martyrs.

Lucy Parsons did not play second fiddle to her husband. While she did not speak at the rally at the Haymarket, she was renowned as a speaker, as well as an activist and agitator, in her own right. A Black woman who did not explicitly engage in Black politics, Parsons contributed to anarchist journal The Alarm and was a founder of the labor union, Industrial Workers of the World. In her later years, Parsons aligned with the Communist Party, organizing and speaking on behalf of the Trade Union Unity League and the International Labor Defense. Yet she remained an anarchist, keeping the memory of Haymarket alive through her biography of Albert Parsons and the trial speeches of the other defendants.

Parsons’ May Day address in Chicago in 1930 radiates with Parsons’ undiminished revolutionary fervor and energy. Parsons recalls the radical history of the labor movement, its continual battle with police terror and capitalist repression, and the ongoing fights for the rights of workers across the globe. To commemorate May Day, we reprint Parsons’ address below.

“I’ll Be Damned if I Go Back to Work Under Those Conditions!”

Address by Lucy E. Parsons, May 1, 1930

I am greatly afraid, Comrades, that my voice will not reach to all of you, but believe me that my spirit will reach to the farthest corners of the room.

I have spoken in this hall before, and in other halls, and one wish I have always wished, that the architect who built a hall like this—with the acoustics that this hall has—would never build another one like it.

Now, I am going to bring you a message, that forty-four years ago today we had our first introduction on American soil of what was known as a great strike. It was the introduction of the eight-hour day in America. From twelve hours to eight hours was a great step, and I have the honor to be one of those who was so instrumental in my small and humble way in preparing for that immense strike.

I have been in the labor movement for many years, I have been in the labor movement since I was a mere girl like these kids I see today. When I saw these little girls with their bright eyes and forward-looking movements, and how bright and happy they were. I went back through all those years and pictured myself, and I said, after forty-four years I see these children who are going to come and take the place of those like myself who will some day, and very soon, of course, pass away. But these will carry on the great fight until the last battle has been fought and won.

I wish I had the strength. I wish I had the wisdom. I wish I was a fine enough speaker to depict to you Chicago forty-four years ago. In my humble way I will try to give you just an outline of it. We had been organizing the working class for nearly a year. Very quietly. They were so downtrodden in those days that the capitalists paid little attention to them, but when the first of May came, and this slogan went forward, “Throw down your arms, throw down your tools and come out,” why, I have never seen such a strike. It was a psychological moment. It was a spontaneous strike, and they came out by the thousands until the capitalist class claimed themselves there were forty thousand who stood out in the streets of Chicago, and when they tried to get them back to work, [replied] “I will be damned if I go back to work under such conditions.”

That was the spirit of that day. That was the dividing line between the long- and the short-hour movement in America. From that day on-there are unions in this city today who were organized then; the bakers union, and other unions. And they have never gone back to the old time. If it had not been for the organization that came into existence just on the heels of this—our leaders were put to death, and after they were put to death there came to the front an organization, a so-called labor organization, the A.F.L of L., the American Federation of Labor. What have they to produce? What have they to show for their forty-six years? They have gone together and scraped together the mechanics, two million in a population of thirty-eight million. They have two million under their banner. The others can go straight to hell for all they care, they are nothing but the common herd.

As I see this movement today, forty-four years from now will tell a different story. Forty-four years from now I believe such a thing will have disappeared. It will have disappeared from the face of the Earth, because I see in this movement today—I have seen many movements come and go. I belonged to all of those movements. I was a delegate that organized the Industrial Workers of the World. I carried a card in the old Socialist Party. And I am now today connected with the Communists [through the International Labor Defense]. So I have seen these movements come and go.

In human affairs, in life, it is just as the ebb and flow of nature. It is like the ebb and flow along the ocean’s way, along the shore of the seaside. Those waves come and play their part and go, but they all leave their imprint, until the ocean itself is worn away with time. And so no one needs to be discouraged because these waves of human forces to the radical movement come and go. They all leave their imprint. The radical imprint, they all leave something behind, and the next great movement like this one that comes, simply steps into the footsteps of those who have gone, and carry it further until the emancipation comes. It is a lesson of history. We do not accomplish all in one day, or one generation. It goes on to the other generations, and I believe, without flattering this organization, that they have the right hope. I can’t help but believe they will go on and on, and will not pass away like the other organizations, because I think they have the substantiality.

Now, I am not going to speak a great while. I want to tell you something about the Haymarket, and then probably I am about through. The movement of 1886, the eight-hour movement was a grand success. For a few days they had the capitalists on the run, you might say. They were taken completely by surprise. We had a great movement trial at that time, and I must, right here and now, I must put in a slight protest for the so-called anarchists in those days. I am an anarchist: I have no apology to make to a single man, woman or child, because I am an anarchist, because anarchism carries the very germ of liberty in its womb. So I do not want to hear that.

Now, we anarchists and others of us here, we carried on this strike. We carried on this movement, and on the third of May—I want to tell you now something you can carry home that will be substantial—on the third of May the McCormick Reaper Works people struck and came out to demand the reduction of hours of daily toil from twelve to ten. They did not even ask for eight hours. That was beyond their reckoning. And on that day the great monstrous meeting was being held, the police went down to that meeting, and they shot and clubbed those innocent people, and the next day the Haymarket meeting was called as a protest against the clubbing and shooting of those people on the day before.

It was a conspiracy of the capitalist class to break up the great movement that was sweeping everything before it. And so this Haymarket was nothing in the world but a conspiracy of the capitalist class to break up the movement of that time. It was a police riot. We were as quiet and peaceful as you sitting here today. But it had its effect. We have always believed it was a detective that threw that bomb in the Haymarket for the purpose of breaking up the eight-hour movement.

Now, beware such scoundrels in your midst. As you go on, they will put up some job like that on you. We know they are capable of doing any kind of work. We believe that bomb was thrown by some detective. The man who threw the bomb at the Haymarket was never known. I am not here to give you a speech on the Haymarket. It was only a great labor movement.

I want you to take it home that the men lying sleeping in the Waldheim Cemetery were simply martyrs to the labor movement. Those of you today who enjoy better conditions, we must enjoy better conditions after forty-four years. There is no such thing as standing still in the world, nowhere in nature, so there has to be some better—today the Communists are demanding six hours or seven hours, rather. Forty-four years from now, and a long time before that time, four hours and even less they will demand, until there isn’t one man or woman in the world who wants to work who cannot get it. That is the kind of movement of the future.

That will not be all. If that is the case, Capitalism will have gone by the board. I do not expect to live that long, but I do believe when I see young people and earnest people who will drop their work in times like this, when work is so scarce, come out in the mid-week and defy the capitalist classes, and come out in the sunlight, and show them as standing solid for shorter hours and better conditions, that that means earnest people and those are the kind of people we have got to have.

The Communist Party has hundreds and hundreds in prison cells. They are there, and before I am through I am going to ask you to send one mighty shout to them of encouragement, that we are supporting them. I will have that in a moment. Now, Comrades, go on with the movement, carry it on, carry it through, because the Comrade has said here, they call us Reds. I don’t know that that is very bad. I do not believe that is a very bad name. We are pretty red. I tell you I am a real Red. The scarlet flag [holding up scarlet cloth].

The workers’ flag, the scarlet flag, the workers’ flag, withal, has shrouded our dead, their lips grew pale and cold, its life bloodstained–their live blood stained its very fold. Then keep the scarlet banner high, beneath its folds we live or and die. We make the flight of ages. It is the flag, and that flag shall fly above the capitalist rampart of capitalism throughout the world, and no woman will be compelled to sell the hallowed name of virtue for a piece of bread. No child will be compelled to go in our factories. No man walking the earth asking for bread that can not get it. It will wave up above the ramparts of capitalism. Then hail the banner of the workers, the red flag throughout the world.

Today we march, we send our greeting upon the ocean's waves, we send them continent to continent, we send our friends across the ocean and all climes and countries: We are with you. Our hearts throb. The working class throughout the world, proclaim the doom of capitalism and wage-slavery.

I have asked the permission of the chair just a moment, I have said something to you about the Haymarket, I haven’t said much about it, and I have brought with me the speeches that were delivered by our comrades, my husband and his comrades, and I wish to say to you that that red flag, that they were shrouded in the red flag, and they lie in their last resting place enfolded in the red flag. But these are the speeches. When they were sentenced to death they were asked if they had anything to say why the sentence of death should not be passed upon them. They arose in the courtroom, and for three days they delivered these masterful speeches.

There has nothing been added of a fundamental nature to the labor movement in those forty-four years. You wonder how those men of that day could have such a grasp of the labor movement. For three days they said to the court, they said, “Honorable Judge”—my husband said, “Honorable Judge, we are not delivering these speeches either to you or to your class. When we are dead and gone, to which we believe we are doomed, this is our message to the world and the working class to know why we were put to death. All these years of my life I have been carrying this message to you, the working class.”

Should any of you wish to read these speeches, they have the cuts of the five martyrs. They are here in the hall. I thank you.