As part of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum, we interview scholars about a recent article they’ve written for either an academic journal or popular publication. We ask these scholars to discuss their article, as well as some of the books that have most influenced them.

This week’s featured scholar is Taija Mars McDougall. McDougall is a PhD candidate in Culture and Theory at the University of California, Irvine. Their article is “Left Out: Notes on Absence, Nothingness and the Black Prisoner Theorist.”

In your article, you refer to George Jackson as a “disavowed theoretician.” What are some of the anti-Black structures, processes, and logics that lead to this disavowal?

Jackson clearly articulates his desire to be a revolutionary communist man and I think the disavowal derives from there. On the one hand, are those for whom the liberal American project is simply a thus far imperfect experiment and that it can be made perfect. These are the ones who would reject the violence but accept Jackson as a smiling, but misguided leftist. On the other hand, are those who respond perhaps unconsciously to the pessimism in Jackson’s work. He tells his addressee that he is haunted by the image of someone standing on the same spot in the same prison two hundred years in the future. This potential failure both of the struggle-as-struggle, but also in getting any serious struggle off the ground is baked directly into his theorizing. Because for blackness as a liberal humanist project to work, liberation has to be not only possible in this world, but has to have happened already in history. Jackson is telling us it has yet to happen and when it does, we could lose and what we have to do to get there will be violent, damaging, and horrible. In the first instance Jackson recognizes in both Soledad Brother and Blood in My Eye that the only way out is through revolutionary rupture, through violence, bringing the US to its knees. He says this clearly, openly and without apology. He does not see a crafty opponent in a game, a misguided or tragic political project or a degraded dreamworld in the United States of America. He sees an enemy and the recognition of a genuine enemy flies in the face of every vestige of every liberal bromide that we who struggle have come to accept. So, the antiblack logic that is leading to these disavowals is in the realm of strategy and political ontology. The liberal tells the black that we are already free because the project is self-perfecting and violence is beyond the pale. The leftist tells the black that we can only but win. So with his desire to be a revolutionary man, a communist man—and importantly not a black man or an African man—this disavowal of his theorizing takes shape. He becomes a solely historical figure, whose work, while read, is read as half history and half manual, rather than as theory of blackness, theory of captivity, theory of war, theory of pessimism, and so on.

How does this “uncitablity of the Black prisoner as theorist” manifest itself in community organizing spaces? I’m thinking specifically of how elite academics and celebrity activists tend to be the sought-after spokespeople and theoreticians for abolitionist movements.

The black is, for me, the dirty secret of organizing. While scholars and big-named activists suck all the air out of organizing, the black, whose needs are not going to be met by the compromise, half-measure or comprador behavior, the black prisoner as theorist, is the ultimate tool. I’m deliberately muddying the distinction because while actually incarcerated blacks are particular, any black person in the struggle can find confirmation of slave status amongst even those most committed and radical of communists and anarchists. It is through us that so much of what is not articulable about the horror of capital is thought, orienting party, formation and org directions, while leaving racial slavery and our actual selves to be devoured by so-called comrades before the police are even called. While we think about ourselves and our predicament as slaves, as workers, as trans- or cis-gendered guys, gals, and non-binary pals, this thinking is a place of replenishment and affirmation for those around us. It always comes from us, and its force is never for us. Our actual thoughts and theories are taken, and we are left behind. Compounding this is the celebrity activist as spokesperson, who can and does leave the imprisoned black by the wayside, their thinking about themselves becoming the stuff of theory for those who go to owned houses, form nonprofits, write books and get distinguished positions in the same places trained to design weapons, carceral technologies, and task forces to launder the violence of the state.

You talk about how the way forward isn’t to fill in the absence with a citation, but to sit with the absence and to sit with the nothingness. Why is this process of sitting with the problem so important in Black study?

When I first started to discuss this missing citation in Anti-Oedipus, I was told to contact the still living translators, University of Minnesota Press, Brian Massumi to ask about it. I checked even the most recent editions of the text to confirm that it was still there and so I had this creeping doubt that the gap was some intentional performance and was supposed to be in the bibliography. But I refused to contact anyone about it and frankly I don’t want to. As soon as that gap is filled, the violence of its appearance is obscured and whatever its ultimate meaning is lost. I really envision whatever theorizing I do from the moment I found it in 2017 as flowing from this void, what I have called an expression of black portraiture—A Portrait of the Black as Critical Theorist. On this low frequency, there is a subtending logic that made it the case that he appears as this strange nothingness in that text and in Gilles Deleuze’s others. It conjures the violence of slavery with the stroke of an inserted blank line and for me, I have to sit with this blank and what it conjures. I saw, here and in so many other places, the violence and its capaciousness, its power, its pulsing desire for everything. I refuse to walk away. Sitting with what has happened, not because we are stunned or frozen, but because the problem is vast and formidable. It is cunning, clever, in our own hearts and minds necessitaing that we think about it deeply and that we don’t stray from it to make ourselves feel better through denial or disavowal. We look the monster in the face, do as Jackson did by recognizing it as our enemy, a paper tiger to be sure, but a paper tiger that cuts, rips tears, bites, speaks, calls out to us in the night saying we can fly if we just jump out the window into its open mouth. For me, this is the core of black study, to really contend with what has been done to us, what ending it would mean and how we live with ourselves together both at the end of the world and after. Sitting in nothingness is something like working-through, in a psychoanalytic sense.

Many BAR readers know George Jackson as a fierce Marxist-Leninist. How did Marxist-Leninism inform his theoretical work? As a Black Studies scholar, what do you see as some of the most important contributions and/or limitations of Marxist- Leninism for Black liberation?

What an incredible set of victories the various Marxist-Leninist parties won through the twentieth century! Seizing whole nations and territories from the capitalist beasts and beginning afresh. And Jackson was, like I am and like many of us are, mesmerized by these victories and their aftermath. One story always gets to me from Black Boleshevik when Harry Haywood recounts the eulogy of a black woman, Jane Golden, in Moscow, illuminating this little moment where political struggle, the winning of a new world, had brought black Americans and colonized people to be trained in the Soviet Union. The eulogy is such a beautiful and devastating moment in that book. I encourage people to read it. But the book itself, like Jackson’s proto-Afropessimism, carries with it not just doubt, but contends with the power of antiblackness. And that is ultimately where Marxism Leninism, anarchism and further developments from there ultimately fail for black struggle. The seductiveness and automaticity of antiblackness is woven into the very fabric of these groups, even when there are these new and very beautiful victories. White chauvinism, as the MLs would call it, powers these groups and refusal to actually attend to it beyond lip-service, causes disintegration of coalitions constantly. Seizing the structure of the state, taking seriously what it means to administer a world, this is key and it is a fairy tale to be believe this wouldn’t be necessary for black struggle, even if the truth of its concept is to seize hold of repetition and set fire over and over. However, the limitation comes from the inherent rejection of working-through antiblackness, which allows nonblack ‘comrades’ to address black comrades as the slaves the former group know them to be and then alibi themselves through taking up more org labor. Refusing to take seriously the raw power and community-forming function of antiblackness and its rituals—it was a black woman’s eulogy where we get this glimpse of a new Soviet world, after all—is the limit of all these left ideologies.

A lot of organizers, artists, and academics can often point to books that helped radicalize them. Are there any books that radicalized you? How so?

There are of course books that have changed me, but they are only explanations for, or acknowledgements that I am not alone or special in, whatever instances of violence I’ve faced, which is what has actually done any sort of radicalizing in me. Assata, an Autobiography and Soledad Brother are the first and foremost as my MA thesis was concerning these two and I was attempting at that time to work out the limits to Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. But I am, if nothing a lover of the classics: Jared Sexton’s Amalgamation Schemes, Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, Frank Wilderson’s Red, White & Black, and the all-powerful Scenes of Subjection by Saidiya Hartman. My good friend, Leah Kaplan, reminds me regularly that we are all a footnote in Hartman’s book, and I take this very seriously because she’s absolutely correct. So much of our work is unspooling what Scenes of Subjection—and Lose Your Mother—has articulated. The last set that have helped—and here I must be unforgivably academic, so apologies—are Marx’s Capital, Lacan’s Seminar XVII: The Other Side of Psychoanalysis, Althusser’s For Marx, Kristeva’s The Power of Horror, Lyotard’s Evil Book and The Differend and of course Anti-Oedipus. I list all these books because there is so much in them, from Hartman to Lyotard, that their readings are interminable and re-reading, again and again, is part of my reading practice; these are books I read and re-read not to memorize but to find new secrets. The last thing that I must mention, giving it pride of place, is a very short letter by a black communist who was killed by ISIS in Syria. Avaşin Tekoşin Güneş (Ivana Hoffmann) wrote a letter to her comrades. It is from Jackson and for her that I work.

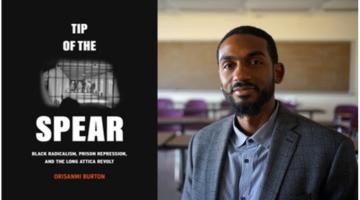

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these works in your future scholarship?

My scholarship tries to get at the infrastructural and the implicative in everything I read. I want to understand its mechanics and then to what those mechanics are in service. What I’m trying to say, I read for counter-purpose and read the same things over and over. (I’m forever impressed at the speed with which some of my peers read!) The books that I have read published in the last years that I recommend to BAR readers thus have this counter-purpose in mind and will be used in this way. The first book is a tie: Ontological Terror by Calvin Warren and Reckoning with Slavery by Jennifer L. Morgan despite my own political posture being opposed to the infrastructures of both books. These books, even with my disagreements, have opened important vistas for Afropessimism and for my own work. The second book I recommend is outside of the realm of Black Studies, but I still think BAR readers should engage with monetary theory and the ways that money operates in the world. Money: 5000 Years of Debt and Power by Michel Aglietta is a great read, accessible, theoretical and vast. It presents some significant resonances that I am working-through in my dissertation, titled Blackness, Terminable and Interminable. This book has helped immensely as I have begun to theorize the black slave as not a commodity, but as money. As ever, there are gaps and absences to address and critique, but I still recommend it highly. Elsewise, I am looking forward to books on the horizon from Denise Da Silva, Selamawit D. Terrefe, Axelle Karera, and Patrice D. Douglass, whose work has already been so crucial to my own.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.