This week’s featured author is Orisanmi Burton. His book is Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

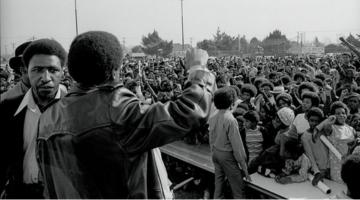

Orisanmi Burton: Although Tip of the Spear covers events that occurred a half century ago, the book is terribly relevant to the present. Resonant examples from recent US history include the urban rebellions in Ferguson, Baltimore, and elsewhere between 2014 and 2015; the National Prison Strikes of 2016 and 2018, which emerged in part, to commemorate the radical prison movement of the 1970s; the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline; the George Floyd rebellions in 2020; the Movement to Stop Cop City, and much more.

In each case, Black and Indigenous people organized multifaceted rebellions against organized abandonment, settler colonialism, racist state terror, and environmental catastrophe. In each case, they faced the wrath of the repressive apparatus of the state in the form of counterinsurgency tactics honed in global laboratories of empire. These examples clearly show the carceral apparatus being used as a political instrument that is weaponized against popular struggles for human rights, democracy, and capacious notions of social transformation. All this is unfolding within the context of the global upsurge in authoritarianism and fascism, which the protagonists of my book were warning us about in the 1960s and 1970s.

Tip of the Spear shows that our current political and social climate is in part the result of decades of carceral repression against Black radical movements, repression that coincided with the flourishing of organized white supremacy that was ignored and, in many instances, nurtured by the state.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

The first half of the book will provide readers with a greater understanding and appreciation for the depth and complexity of the US prison movement of the 1970s, and how the so-called dregs of society – the economically dispossessed, the formally un-educated, the Wretched of the Earth, those deemed surplus – developed a revolutionary consciousness, formed organizations, and engaged in a collective struggle, a counter-war that secured several tactical victories in the face of determined opposition. I want to make their strategies and tactics, as well as the contradictions they were working through visible; because movements of today are facing many of the same challenges and many of the same contradictions, even though the context is different.

Any successful social movement will need to have a sophisticated understanding of repression. The second half of Tip of the Spear offers a systematic account of the state’s response to the Long Attica Revolt, and to the prison movement more broadly, a response that took the form of a domestic counterinsurgency. While technologies of state repression have developed significantly since the period covered in the book, the basic method has remained the same. While it’s not especially complicated, it can be very effective. The basic premise is the same as it was in ancient Rome: “Divide and Conquer.” Administrators of counterinsurgency respond to radical and revolutionary movements by striving to calibrate terror-inducing violence with seductive and solicitous reforms. The goal is to incorporate the assimilable elements of the movement into reformist state projects, while simultaneously isolating the unassimilable elements – rendering them easier to “neutralize.” This strategy is used again, and again, and again, and I went through great pains to show it happening so that hopefully it will be easier to recognize and counter.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

Part of my argument is that our collective understanding of the prison movements of the 1970s has been incarcerated and domesticated, which is to say that when analyzing these movements, the tendency has been to narratively police and confine the aspirations of the movement’s protagonists to demands for improvements to prison conditions and to truncate the internationalism inherent in many of their struggles.

I show that this is not accident. That it is by design. A key part of the counter-abolitionist movement was to incarcerate radical, revolutionary and abolitionist ways of knowing, modes of analysis, and forms of organization. A central aspiration of this book is to decarcerate this criminalized knowledge. This is critical since much of the language and many of the conceptual tools we use to analyze historical movement, I argue, grow out of the counterinsurgency arrayed against that very movement, a counterinsurgency that unfolded on narrative, psychological, and cognitive terrains. In order to research and write this book from the perspective of the revolutionaries who led the struggle, I had to un-learn carceral and colonial ways of thinking about the world, about the human, about politics, about time, about violence . . . Perhaps reading the book will help others do the same.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

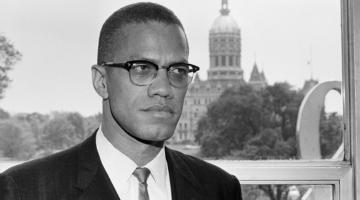

One of the primary goals of the book is to elaborate Black radical theories that emerged from the most repressive institution in US society and to show these theories in action, to show their unfolding as praxis amid a concrete confrontation. I’m thinking with and through the works of revolutionary and anti-theorists situated in the Third World: Mao, Che, Fanon, Nkrumah, Césaire, Wynter, Cabral, Freire, and Eduardo Mondlane. The protagonists of my narrative were reading these thinkers and struggling to put their ideas into practice. The book features appearances from intellectuals we know of or should know of: Queen Mother Audley Moore, Malcolm X, Safiya Bukhari, Assata Shakur, Dhoruba bin-Wahad, Jalil Muntaqim, Kuwasi Balagoon, among others. But it also features obscure, unknown, and anonymous thinkers and theorists whose intellectual production was nothing short of remarkable. In this way, the book is an attempt to elaborate what imprisoned intellectual Stevie Wilson, building on scholar Cedric Robinson, calls the “imprisoned Black Radical Tradition.” It is my effort excavate and present the invaluable archive of hidden, criminalized, and incarcerated knowledge.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

I think Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War by Vincent Brown is a really important text. Brown analyzed slave revolt as a “species of warfare” and performed meticulous historical research to bring the strategies, tactics, and consciousness of enslaved people to life. The notion that slavery was never actually abolished, which we find asserted by W.E.B. DuBois in Black Reconstruction, among many other sources, suggests then, that to be Black is to be ensnared in a centuries-long war. This is highly relevant to my main argument which is that the prison is a domain of war.

The other book I would recommend is Damien Sojoyner’s Against the Carceral Archive: The Art of Black Liberatory Practice. The book invites us to think about the prison as a paradigmatic site of white Western knowledge production. For Sojoyner, the brick-and-mortar prison that incarcerates human bodies is but one expression of a much larger and more diffuse carceral archive. Sojoyner traces the other expressions of this carceral war on alternative ways of knowing and thinking. He also examines organic practices of Black radical organization that contest and exceed this regime. The book is highly theoretical but also grounded in Sojoyner’s deep ties to the communities he’s studying, as well as his research and activism in the Southern California Library, a community archive based in the heart of Black South Los Angeles.

Like Tip of the Spear, these texts raise questions of epistemology, history, war, violence, captivity, and methodology. These are critical themes that any serious engagement with Black radicalism will have to contend with.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.