A Maasai man on tribal-managed lands. HEMIS / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Carbon and biodiversity offsets are the latest imperialist weapons used against African people and their nations. Self-determination is the key to ecological health for the continent.

“Unless the Third World has the right to develop, the ecological problem cannot be solved on a just basis in the First World.” - Max Ajl, A People’s Green New Deal

This commentary provides an overview of carbon and biodiversity offsets as an expansion of global capitalism under the western environmental agenda marshalled against development in Africa. I draw from my essay, Imperialism is the Arsonist of our Forests: Towards an African Climate Agenda, published in The Republic, where I expand on this issue and propose a pathway towards an African climate agenda that is predicated on our right to meaningful development.

Neoliberal environmental agenda and ‘ecological imperialism’

The exuberance of carbon and biodiversity offsets reached its pinnacle in Africa with several governments signing deals to concede vast sections of their primary forests to global carbon markets. Essentially, carbon and biodiversity offsets are premised on the flawed logic that forests, rangelands, mangroves and other important ecosystems of the world peripheries can serve as carbon sinks and neutralise the ecological effects of the unsustainable economic growth of the imperial core. The 2022 Land Gap Report estimates that the total area of land needed to meet climate pledges is almost 1.2 billion hectares globally. Consequently, protected areas whereby governments evict local communities to set aside land for conservation, are being incorporated into global markets where US, EU and Asian based corporations can extract and trade carbon and/or biodiversity credits to ‘offset’ their environmental destruction. They represent the new brand of capitalist solutions to the ecological problem that capitalism birthed, while Africa’s right to development is, yet again, postponed by the neoliberal environmental agenda. The late Zimbabwean land reform activist, Sam Moyo, captured this well, noting:

“Ecological imperialism and the effects of ‘North’ driven climate-change agenda are increasingly marshaled against agrarian development from below. The introduction of ‘carbon trading’ measures through aid, which seek to reserve more African land and biodiversity for external forces, tend to further displace peasant socio-economic processes.”

Agrarian, pastoralist, and riverine communities whose livelihoods ecological knowledge and indigenous technology have maintained the resilience and biodiversity of these ecosystems, have long been assaulted by the neoliberal environmental agenda. For these communities, the foregone social, cultural and economic values of protected areas including food security, water for irrigation and hydroelectricity cannot be overstated and defy any calculation. The Global South accounts for two-third of almost 17 percent of the world territorial cover of protected areas. African countries such as the Republic of the Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia, and Guinea have each set aside between 35 to 42 per cent of their national territories for biodiversity conservation, compared to 13 per cent in the United States. The devastating impacts of protected areas on local communities are well documented including massive displacements from their ancestral lands. It has been estimated that 136 million people worldwide have been displaced from only half of the current protected areas. Today, the ascendency of carbon and biodiversity offsets is causing the further dispossession of African rural communities under the north-driven climate agenda.

The state of carbon and biodiversity offsets in Africa

In 2023 alone, several African countries signed contracts to concede vast sections of their primary forests to UAE, Europe and US-based corporations to extract and trade carbon credits. These deals cover land masses of 20 per cent of Zimbabwe, 10 per cent of Liberia, 10 per cent of Zambia, and 10 per cent of Tanzania and more contracts are expected to come from other countries. In Kenya, the government signed a controversial deal conceding millions of hectares of the Mau forest leading to the forced evictions of the Ogiek community. In Senegal, large-scale reforestation projects covering 25 per cent of the mangrove forests of the Saloum Delta, one of the largest wetlands in West Africa, are slated to turn into carbon deals financed by oil giant, Shell.

This string of contracts came after Gabon set a precedent at One Forest Summit in December 2022 to make carbon credits available under the United Nations Framework on Climate Change. The summit was co-hosted by the French government. In August 2023, the country completed the first debt-for-nature swap in continental Africa covering 25 percent of its territory earmarked as protected. The deal was arranged by Bank of America and the International Development Finance Corporation which is the corporate arm of the World Bank working with private companies. Furthermore, The African Climate Summit (ACS) hosted in Nairobi in September 2023 by Kenyan President, William Ruto, under the tutelage of European governments and international institutions, was a bold endorsement of the north-driven neoliberal environmental agenda. But for local communities, carbon and biodiversity offsets and other nature-based solutions cut at the heart of their struggle for resource sovereignty and development.

Carbon and biodiversity offsets impacts on local communities

Numerous reports emerged in the last year documenting the devastating impacts of offset projects on these communities. The Oakland Institute presents several case studies of offset deals by investment firms in East Africa, including Sydney-based New Forest with a portfolio of 1.27 million hectares of land, causing violent evictions and dissemination of livelihoods. Similarly, an investigation by Propublica exposes the devastating impacts of a biodiversity offset project in northwest Guinea, funded by the International Finance Corporation. According to the report, the expansion as well as the offset project has enabled the devastation of villages and helped a mining company justify the death of endangered chimpanzees in the area.

Despite the damning evidence of their impacts, African governments and environmental organisations present offset deals as a mechanism to generate revenues for local communities. Yet so far, the economic benefits of offset schemes to local communities remain elusive. I’m currently exploring this issue in Senegal, where some communities in the Saloum Delta have been able to generate income by supplying propagules for the mangrove reforestation campaign organised by Wetlands International, the French Development Agency and carbon credit broker, WeForest. However, local officials shared with me concerns that this income is used to obtain the buy-in of impoverished communities. There is also great uncertainty about their capacity to generate revenues or access resources after the deal is signed between the government and the carbon buyer.

At a moment of emerging political and economic interests against the backdrop of a rapidly changing natural environment, it is also crucial to grasp how the Western climate agenda functions within these shifting global structures. Thus, it’s important to ask, beyond local impacts, how do carbon and biodiversity offsets shape global economic configurations?

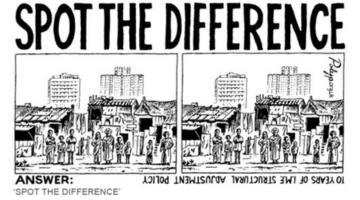

The effects of offset deals beyond local impacts

It may be too early to know for sure how offset deals will impact local and global economic structures in the long run. But the record from over three decades of ICDPs can help us gauge their possible trajectories. Carbon and biodiversity offsets schemes have existed in various forms since the late 1980s through a host of integrated conservation and development programs (ICDP) advanced by Western environmental agencies and implemented mostly in the Global South. ICDPs are market-based approaches allegedly designed to channel economic benefits for community development while preserving the natural environment. But for the most part, ICDPs seek to fundamentally change the social structures of resource-dependent communities of the peripheries without challenging, but rather strengthening, the global economic structures that are the main drivers of our ecological problem.

ICDPs include tourism-based conservation projects, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) and Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES). In reality, except for PES which works directly with farmers and landowners, most ICDP schemes demand that local communities cede control of their land and resources in exchange for employment and vital public services for communities already living under the weight of state-sanctioned deprivation. Nigerian environmental researcher, Adeniyi Asiyanbi, has demonstrated how REDD+ facilitates a regime of forest militarization that curtails local resource access while driving elite accumulation in timber forestry. Similarly, my research among many other studies, shows that in most of Africa, tourism-driven conservation programmes, give greater advantage to private tour operators, while undermining local resource use practices and entrepreneurial activities, thereby exacerbating structural inequities.

I have written before in The Republic, imperialists and their African allies invoke environmental discourses to galvanise the dispossession of African lands, opening them to new markets and extractive concessions for US, European and Asian corporations. Furthermore, the body of work of Senegalese agrarian economist and feminist, Rama Salla Dieng, demonstrates how land dispossession deepens class and patriarchal structures in African rural societies while reshaping agrarian labour relations between the world’s capitalist core and its peripheries. Today, as Sian Sullivan maintains, carbon and biodiversity offsets market, as with any new frontier, enables the penetration of finance capital into an expanding array of environmental conservation niches. This process sets in motion the primitive accumulation of land and the elimination of endogenous socio-economic systems to support the reproduction of global capitalism.

Agrarian movements offer a path toward development in an ecologically just world

The imperialist capitalist project is at its offensive on all fronts in Africa today. The solutions to the climate and ecological crisis, imposed by the international climate agenda are neocolonial and capitalist ones that exacerbate unequal global development patterns. There is an urgent need for an African environmental agenda that prioritises the sovereignty and meaningful development of African nations. African agrarian systems offer important lessons towards an economic and ecological just world.

The 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reports that the continent still holds a quarter of the world’s biodiversity hotspots and some of the most ecologically intact communities. Empirical evidence shows that the resilience of these landscapes is the outcome of agrarian systems that are life-sustaining for the human and non-human world. In his seminal 2013 book, From Agriculture to Agricology: Towards a Global Circular Economy, Ugandan scholar, Dani W. Nabudere, documents how African agrarian systems contribute directly to food production, livelihoods and cultural sustenance while preserving biodiversity, forests, soil organic matter, rangelands, and other ecosystems critical for averting the climate crisis. Similarly, my research in the Transboundary Biosphere Reserve of the Senegal River Delta, adds to the body of evidence that building rather than replacing socio-economic processes of pre-existing agrarian systems yields better conservation and development outcomes. Therefore, agrarian societies play a key role in transitioning to endogenous socio-economic systems as essential to averting the ecological and climate crisis.

There is another strong case to be made for why African agrarian movements should be central to climate actions and biodiversity conservation. Industrial agriculture is not only one of the largest carbon emitters and causes of biodiversity loss. Its global political and economic infrastructure also fuels the ongoing dispossession of African lands, eliminating the endogenous agrarian systems. The Oakland Institute reports that in 2009, Africa accounted for 70 per cent of the 56 million hectares worth of large-scale farmland deals. By 2016, an estimated 42.4 million hectares of land had come under contract, one-third of which involved land formerly used by smallholders. This trend is expected to intensify with the high volatility of food prices in Global North countries.

Fortunately, agrarian organisations on the continent such as the Kenyan Peasant League and African Centre for Biodiversity are fighting for food sovereignty as central to slowing the expansion of industrial agriculture that is accelerating the biodiversity and climate crisis. We must also pay attention to and support grassroots agrarian organisations like the Yèlimi founded by Blandine Sankara in Burkina Faso, and DyTAES in Senegal, who present pathways towards a more just climate and ecological future that is predicated on Africa’s right to meaningful development.

Aby L. Sène is assistant professor in parks and conservation area management at Clemson University.