Somaliland President Muse Biho Abdi and his delegation met various officials, including Sen. Chris Van Hollen, in Washington in March 2022. This was one of many meetings between officials from the US, EU, and secessionist Somaliland. (Photo:US State Dept)

As Somaliland forces continue to fire on Somali nationalists in Laasaanood and the surrounding region, Sool, Sanaag and Cayn, US/EU/NATO officials held a joint call with secessionist Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi.

On April 17, a group of 15 international partners—Belgium, Canada, Denmark, European Union, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Turkey, United Kingdom, and the US—issued a statement about their conversation with Somaliland secessionists waging war against Somali nationalists in the Somali city of Laascaanood and the surrounding region, Sool, Sanaag and Cayn.

The diplomats plodded through the usual platitudes, calling for a cessation of hostilities and urging both sides to sit down and talk but, most fundamentally, reinforcing the West’s de facto recognition of secessionist Somaliland, encouraging the further fracturing of Somalia and disrespecting the nation’s sovereignty.

Why were they engaging in direct conversation with secessionists? The report resembled those of Antony Blinken regarding his meetings with the seditious Tigray People’s Liberation Front, meetings which disrespected Ethiopian sovereignty. Somaliland aspires to be the Taiwan of Africa, and Western officials can’t do enough to encourage it.

Their statement ended with this startling sentence:

“Partners were disappointed that H.E. [His Excellency] the President did not commit to a withdrawal of Somaliland forces centered around Laascaanood.”

One might at first think that they were referring to Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, but no, the “H.E. the President” they’re disappointed in is Muse Bihi Abdi, the “President” of Somaliland, one of Somalia’s seven federated states.

The Somali president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, hasn’t objected to being left out of the conversation. His only response to the conflict has been to mumble that both sides should talk and try to work it out, even as hundreds of people die and as many as 100,000 may have been displaced.

Somalia has a flag and a UN seat but hasn’t had much else since the collapse of the Siad Barre government that existed from 1969 to 1991. The Islamic Courts established welcome stability between 2000 and 2007, but a 2006 US-backed invasion by Ethiopia overthrew the courts, inspired extremism, and gave rise to Al Shabaab, the terrorist organization that has plagued the nation and served as the excuse for US drone bombing and military presence ever since.

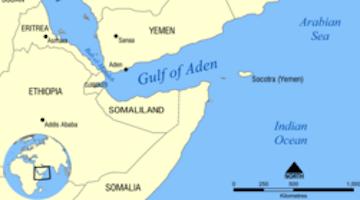

The Somali coast is as geostrategic as any in the world, along the Gulf of Aden, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean, and it may have the richest untapped oil reserves in the world, so whatever the US’s actual concerns with Al Shabaab are, US military presence in Somalia is about more than Al Shabaab. The navies of multiple world powers swarm all over these waters, where roughly 12% of the world’s trade passes through the Suez Canal, and roughly 50% of its oil passes through the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz.

President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has no objection to drones bombing the Somali landscape, frequently hitting innocent nomads, farmers, and the livestock that often represents an entire family’s wealth. Nor does he object to the increasing US troop presence, or expansion of the US air base, Baledogle Airfield, command center for US drone operations in Somalia and training center for the Danab Brigade, a US trained, commanded, and paid special operations force.

He has no problem with ATMIS, formerly AMISOM, the UN Peacekeeping operation that has failed to keep the peace since its inception in 2007.

According to Somali scholar and Horn of Africa Institute founder Abdiwahab Sheikh Abdisamad, “President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud is a foreign project and has no vision and mission for the country. He has no political philosophy to defend. He is simply there to enrich himself.”

Farmaajo tried to build a sovereign military to defend a sovereign Somalia

Somalia’s last president, the hugely popular Mohammed Abdullahi Mohammed, aka Farmaajo, was quite a different story. He was trying hard, within extreme circumstances, to negotiate the exit of US and other foreign troops and build a sovereign Somali military capable of defending a sovereign Somalia.

So Farmaajo had to go. The last thing the US and its EU/NATO allies want to see is a strong, sovereign Somalia exercising control over its own vast oil resources and its geostrategic coast, and even—shudder—forming a regional trade, cultural, and security alliance with its neighbors Ethiopia and Eritrea.

With staggering hypocrisy, the US used the IMF to batter Somalia into holding a corrupt, clan-based election in 2022, when Farmaajo and the nationalist, aka unionist, movement was struggling for universal suffrage, a one-person-one-vote election. Farmaajo was out, and Hassan Sheikh Mohamud was back into the office he had misused from 2012 to 2017.

It often seems against all odds that Somalis will ever have a functioning nation again, but Somali unionists are determined, and they don’t have to struggle with the ethnic divisions that have to be overcome in so many African nations because colonial boundaries were drawn without regard to whether the people inside them shared language, culture, or religion.

“Somalis speak one language, share one culture, and practice one religion,” says Somali American organizer Abdirahman Warsame, “and Somalia will become a nation again.”

Ann Garrison is a Black Agenda Report Contributing Editor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. She can be reached at ann(at)anngarrison.com.