“In a slaveholding society such as ours, even after the formal institution of chattel slavery has ended, each and every legal principle ultimately expresses the foundational antagonism between non-black and black.”

When Siwatu-Salama Ra was sentenced to two years in prison for brandishing an unloaded, legally registered gun, in a jurisdiction with a “stand your ground” statute, the state of black self-defense suffered another damaging, albeit predictable, blow. Ra used her gun to get a neighbor who was attacking her and her family to back down. The neighbor had rammed her car into Ra’s car, in which sat Ra’s two-year-old child, and then attempted to run over Ra and her mother. Writing about the case recently, Patrise Cullors noted:

“Michigan has a specific law,popularly known as the Stand Your Ground law to protect people who act by using a firearm to defend themselves from another person who they believe is going to cause unlawful harm to them if there is ‘an honest and reasonable belief that force is imminent.’ However, instead of the law working for Siwatu, it was used against her.”

What is the legal context in which Ra sought to defend herself and her family? And what about the right to self-defense against police violence?

In 1900, the Supreme Court in Bad Elk v. United Statesfound that Bad Elk was within his rights when he shot the police officer that was attempting to arrest him because the attempted arrest was unlawful. Under such circumstances, where a law enforcement officer attempts an arrest without probable cause, Bad Elk explains that the defendant cannot be charged with “resisting arrest” or “assaulting an officer,” and any injury or death to the officer cannot be “murder” or “attempted murder.”[i] Additional court decisions before and since Bad Elkaffirm this basic principle of self-defense, even against the police.

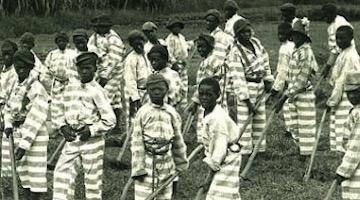

“The same year that the Court found John Bad Elk had the right to self-defense against unlawful arrest, there were 106 black lynch victims.”

The same Supreme Court that decided Bad Elk in 1900, however, had only four years prior come up with its landmark “separate but equal” doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson.[ii] What, then, does “separate but equal” mean for the matter of self-defense? The same year that the Court found John Bad Elk had the right to self-defense against unlawful arrest, there were 106 black lynch victims, or an average of two lynchings per week.[iii] The Court’s reasoning in Plessy is well-known: government may make civil and political equality, but it cannot compel social equality. In this the Court was echoing the earlier Dred Scott v. Sandfordcase in which it stated that Scott had no juridical standing because he had no political standing: his degradation was not the result of law or jurisprudence, and hence it was not a matter for the courts. Rather, the Court said, Scott was degraded simply because he was black.

The Court’s reiteration of the right to self-defense against unlawful arrest for non-blacks in the Bad Elkcase is thus elaborated within the penumbra of Dred Scottand Plessy. Black self-defense before the law falls within the basic principles that black people have “no rights which the white man is bound to respect” (Dred Scott) and that black and non-black societies are “separate but equal” (Plessy). A full review of the law on self-defense would need to re-evaluate Fourth Amendment case law in light of these principles. In other words, it would need to be done in real terms—meaning, within the context of the racial hierarchy in which law arises and to which it refers.

For instance, while most of the major cases through which the courts have steadily circumscribed the Fourth Amendment’s protections in the face of police powers have directly occurred at the expense of black defendants, I would suggest that white people today doretain the right to self-defense specified in Bad Elkand numerous other cases.[iv] The recent appearance of “stand your ground” laws, which are simply enhanced reiterations of Bad Elk, the successful use of these “stand your ground” laws by non-black defendants, and the ability of white people to legislate and practicetheirarmed self-defense in the form of open-carry laws, so-called “free speech” militias and the like, also needs to be considered in this overall appraisal of self-defense law.

“Black self-defense before the law falls within the basic principles that black people have “no rights which the white man is bound to respect” (Dred Scott) and that black and non-black societies are “separate but equal” (Plessy).

Finally, the efficacy of non-black self-defense before the law is dependent upon the presence of a black threat, actual or imagined. In a slaveholding society such as ours, even after the formal institution of chattel slavery has ended, each and every legal principle ultimately expresses this foundational antagonism between non-black and black, between the freedom of self-possessing human subjects and the un-freedom of objectified beings construed as black and dangerous. Ultimately, this is why black people are disqualified from exercising self-defense, because they cannot personify danger and risk, and at the same time, possess the capacity to ward off the very threat that they embody. “Stand your ground” statutes, therefore, do not cover black people who use firearms to defend themselves against actual bodily harm, as in Ra’s case or in Marissa Alexander’s case before her.

What would it mean for black people if the law recognized their ability to defend themselves against imminent threats, or to resist unlawful arrest, even to kill an officer who attempts to restrict their free movement unconstitutionally? With the Korryn Gaines case, we got a glimpse of the converse—of what it looks like when a black person stares down the law’s phobic response to black self-possession. Gaines was killed by Baltimore County police officers on August 1, 2016 when they attempted to serve a warrant for her arrest on a minor traffic violation and she attempted to defend her home with a shotgun. The standoff at her home was precipitated by a series of harrowing experiences at the hands of police, where Gaines and her child were assaulted, she was beaten, held in isolation for two days with no water, may have had a miscarriage as a result, and was charged with assaulting an officer and resisting arrest—all as a result of a traffic stop for an offense punishable only by a ticket. As Gaines put it afterwards, she realized that she was “a hostage from the very beginning of the traffic stop.”[v] Not even the presence of the SWAT unit, nor the presence of the legally purchased and registered shotgun that Gaines used to defend her home, justify her death.[vi]

After Gaines was killed, the website Blavity.compublished a roundup of eleven highly publicized incidents from the last couple years where police were able to disarm white people without killing them. This includes the 177 bikers involved in the Twin Peaks shootout in Waco, Texas, in 2015;[vii]the man who killed three people and wounded nine in an attack on a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs in 2015;[viii]and Dylan Roof, who killed nine people at the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, SC in 2015 (not only did the police not shoot Roof, but they bought him a meal at Burger King after arresting him on their way to the police station).[ix] Most recently, we have the example of the Toronto police officer who arrested the man suspected of driving a van onto a crowded Toronto sidewalk, killing 10 people on April 23, 2018. This officer did not feel it was necessary to shoot the van suspect, even after the man warned the officer that he was armed, pointed his weapon at the officer, and implored the officer “kill me, kill me.”[x] Mind you, none of these white gunmen were acting in self-defense, and yet the police treated them with the respect that the right to self-defense presupposes. In short, we have ample evidence that neither Second or Fourth Amendment protections apply to black people. Although black self-defense may be prohibited legally, it must continue to be practiced in black thought.

Tryon P. Woods teaches Crime & Justice Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth and Black Studies at Providence College. He is the co-editor of On Marronage: Ethical Confrontations with Antiblackness (Africa World Press) and Conceptual Aphasia in Black: Displacing Racial Formation (Lexington), co-author of the forthcoming Ex Aqua: The Black Mediterranean and the Excavation of Black Power (Manchester UP), and author of the forthcoming Blackhood Against the Police Power: Punishment and Disavowal in the “Post-Racial” Era (Michigan State UP).

[i] Bad Elk v. United States 177 U.S. 529 (1900).

[ii] Plessy v. Ferguson 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

[iii] Lynchings by Year and Race Table, available at http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/shipp/lynchingyear.html; accessed October 10, 2017.

[iv] Terry v. Ohio392 U.S. 1 (1968); Florida v. Bostick501 U.S. 409 (1991); Whren, et al. v. United States517 U.S. 806 (1996); Illinois v. Wardlow528 U.S. 119 (2000).

[v] Breanna Edwards, “Everything We Know About Korryn Gaines,” The Root, August 2, 2016, http://www.theroot.com/everything-we-know-about-korryn-gaines-1790856303.

[vi] See the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland statement following Gaines’ killing: https://www.facebook.com/ACLUMD/photos/a.457364618765.254729.20188298765/10154381158403766/?type=3&theater.

[vii] Holly Yan and Jeremy Grisham, “48 More Bikers Indicted in Deadly Shootout at Waco, TX Restaurant,” CNN.com, March 24, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/03/24/us/waco-more-bikers-indicted/.

[viii] Bill Chappell, “Planned Parenthood Shooting Suspect Robert Lewis Dear to Appear in Court,” National Public Radio, November 28, 2105, http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/11/28/457674369/planned-parenthood-shooting-police-name-suspect-procession-for-fallen-officer.

[ix] Jason Silverstein, “Cops Bought Dylan Roof Burger King After His Calm Arrest: Report,” New York Daily News, June 23, 2015, http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/dylann-roof-burger-king-cops-meal-article-1.2267615.

[x] https://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2018/apr/24/toronto-police-officer-single-handedly-arrests-van-driver-suspect-video.