At the 1972 event, Walter Rodney proclaimed that “black unity must be international because we live on every continent, through no choice of our own.”

Editors, Black Agenda Review

“We are saying ‘yes’ to the struggle in Africa today … And we are saying ‘yes’ to people like the Soledad Brothers and the martyrs of Attica.”

“We are saying ‘yes’ to the struggle in Africa today … And we are saying ‘yes’ to people like the Soledad Brothers and the martyrs of Attica.”

African Liberation Day (ALD) has its origins in the early days of independent Africa. Delegates at the First Conference of Independent African States, convened by Dr. Kwame Nkrumah and held in Accra, in 1958, called for an “African Freedom Day,” to be held on April 15, to honor those who had contributed to the anti-colonial struggle. With the founding of the Organization of African Unity in 1963 in Addis Ababa, African Freedom Day became African Liberation Day. Commemorated on May 25th, the purpose of ALD is to draw attention to and support the ongoing Pan-African struggle against colonialism, imperialism, and white supremacy.

It was not until the 1970s that ALD began to be commemorated in North America. This first was prompted by the Pan-African Secretariat of Guyana’s call in 1970 for the celebration of ALD in the Americas. As a result, there were ALD actions in Georgetown, Guyana and small gatherings in the US and Canada.

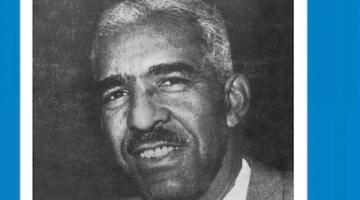

Two years later, ALD events were organized through the efforts of Owusu Sadaukai (Howard Fuller), the founder and president of Malcolm X Liberation University in Greensboro, North Carolina. In 1971, Sadauki had spent forty-five days in Mozambique. He met with leaders of the liberation fronts in southern Africa and was told of the importance of Africans in the diaspora to the success of the struggles on the continent. Upon his return to the United States, Sadaukai formed the African Liberation Day Coordinating Committee (ALDCC) with former SNCC member Cleveland Sellers. A broad based, non-sectarian organization, the ALDCC included some fifty members including Ralph David Abernathy, Angela Davis, John Conyers, Jr. Charles Diggs, H. Rap Brown, Jesse Jackson, Imamu Baraka, Nathan Hare, and Huey P. Newton. By 1972, Sadaukai was making connections across the US, Canada, and the Caribbean to promote the formation of local African Liberation Support Committees for a day of protest on May 27 -- a month after Kwame Nkrumah succumbed to cancer in Romania.

“A broad based, non-sectrian organization, the ALDCC included some fifty members”

Support for the ALDCC’s ALD activities was widespread. Interest in ALD was buoyed by a disgust with US imperial policy and anger at US corporate financing of the apartheid regimes, combined with an emerging pan-African consciousness in North America that included support for the armed struggle of the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and the Cape Verde Islands (PAIGC), and the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA). Indeed, while Black students and Black labor were demonstrating US complicity in colonialism in Africa, the Congressional Black Caucus sponsored a bill compelling US corporations to liquidate their holdings in South Africa while paying reparations to the African people. For its part, the ALDCC organized conferences on the U.S. and South Africa in Washington in March 1972 and joined rallies at the Portuguese embassy in DC to protest the bombing of Tanzania.

On May 27, ALD protests were held in Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Toronto, and Antigua and Barbuda. The largest of these demonstrations occurred in Washington. Between 20,000 and 25,000 people marched from Malcolm X Park and down Embassy Row, stopping at the Portuguese Embassy, the Rhodesian Information Center, the South African Embassy, and the US State Department, before staging a rally at the Washington Monument -- which was renamed Lumumba Square. Speakers included Sadaukai, Walter Fauntroy, George Wiley, Imamu Baraka, Don L. Lee (Haki R. Madhubuti), and Cleveland Sellers, who read a message from Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture). In Toronto, ALD protests were organized by Horace Campbell and Rosie Douglas. Between five and eight-thousand people met at Christie Pits (which was renamed Henson-Garvey Park) to hear Douglas, Julian Bond, and John Conyers. In San Francisco, between five and ten thousand people marched through the Fillmore District to Raymond Kimball park where they heard speeches from Bobby Seale, Walter Rodney, David Sibeku, and Gary, Indiana mayor Richard Hatcher. Significantly, promotion for ALD was largely done through Black community newspapers and Black radio.

The euphoria and the radical pan-African sensibilities of ALD ’72 soon deteriorated because of differences in ideology and strategy among individuals and organizations. It would seem that Sadaukai’s ALDCC began to abandon its commitments to Pan-Africanism, to African liberation, and to Africa as the primary focus of African Liberation Day. The All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP) eventually accused ALDCC members of opportunism, claiming that they took advantage of Pan-Africanism when it was expedient to do so even though they had no real commitment to Pan-Africanist principles and politics. Over the coming years, the A-APRP would fight to bring “African Liberation Day Back to Africa.”

“Promotion for ALD was largely done through Black community newspapers and Black radio. “

An editorial in Black Unity, a publication of the Bed-Stuy community organization The East, discussed the “confusion and conflict” over ALD in 1974. The editorial described a “southern strategy” deployed by an alliance of Black nationalists and white socialists to exclude Pan-African organizations from ALD. As a result, the editorial argued, the ALD demonstration in Washington, DC was little more than a “wine drinkin refer smokin picnic,” while the subsequent march appeared to be led by the police. For Black Unity, ALD had become an embarrassment to anyone truly interested in African liberation and it was critical that ALD should be reclaimed by the Pan-Africanists.

As an example of what this Pan-African reclamation would look like, Black Unity reprinted Walter Rodney’s 1972 ALD address in San Francisco. Titled “The Meaning of African Liberation Day,” Rodney’s speech provides a timely reminder of what ALD is, and why it remains important.

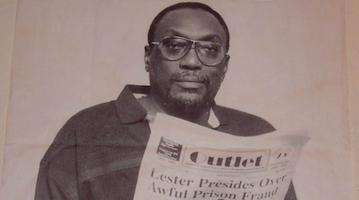

The Meaning of African Liberation Day: A Speech Delivered May 27, 1972 in San Francisco, California by Dr. Walter Rodney

I was born in a place that used to be called British Guyana. I happened to have been educated in Jamaica, to have lived among Black people in England and on the Continent. I have met brothers and sisters who say that their mother-tongue is, quote-un-quote, “French, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese,” as well as English which we speak. And because of this, we have a problem of identification: we do not know who we are! And that is why this gathering is of great symbolic importance, because it is an act of identification.

We are saying that we identify with the African people of the African continent. We are saying that we are an African people. And when we make this identification, we have no illusions about the fact that this is a very revolutionary initiative; it is a rejection of every other form of identification which the white society has asked us to accept.

Let me draw your attention to something which white universities and white libraries practice; and this is a university community; numerous universities lie around this land (Bay Area): go into their libraries and check the Library of Congress cards under Europe or European, you will find all entries listed concerning the Continent of Europe; you will also find entries listed about Europeans in East Africa; Europeans in Asia and Australia.

Look under the Chinese, you will find entries listed not only for Mainland China, but for Chinese in Malaysia, and for Chinese North America, but look under Africa and Africans — the only entry under Africans relates to the Continent itself — there are not entries under Africans overseas — there is no such category. Africans who have been raped from the Continent mysteriously disappear and become “Negroes”!

“We are saying that we are an African people.”

So when we reject the very term “negro,” it is not playing with words; negro is a conception — when we reject the term negro it is a rejection of a whole historical interpretation because (get it very clear) negro is a thing! a negro is not a person!

Historically, when we were taken as slaves, we were dehumanized, we were converted from people into things! In the literature of slavery, a slave is referred to, an African is referred to as apiece. The Portuguese will say, “We have thousands of pieces, hundreds of pieces” — those are Africans to whom they referred.

We were brought to this section of the world and we were auctioned; and auction is something reserved for antique furniture. We were brought to this section of the world and in Washington and in Virginia and in Maryland (my God, in Maryland a cracker was shot the other day); in places like that, we were bred as slaves, they were slave breeding grounds. Now breeding of that sort is reserved for stud animals, so the negro was a thing — at best and animate object in the category of cattle, horses and sheep. So when we break with that and say we are an African people, that is a revolutionary identification.

“Negro is a thing! A negro is not a person!”

I do not say to understand who we are is the be all and end all — on the contrary, it is merely a very short step forward in the struggle, because freedom is a long road — freedom is the road which the Vietnamese people travel on the Ho Chi Minh trail; each man and woman carrying 60 pounds weight. Freedom is the long road which the Brothers from Angola, in which the Movement of the Popular Liberation of Angola, that is the road which they take week after week, crossing Eastern Angola, indeed, crossing Zambia, crossing the plains, crossing the flooded rivers, crossing the swamps, to engage with the enemy — that is the road of freedom.

Freedom is the road which carried in Guinea (Bissau), along the creeks and the rivers, the Brothers take the canoes to engage the enemy. Therefore, I am not saying that the identification is all — it is a process of struggle — and when we support Africa today, let no one have the impression that we are supporting a passive people. Because the news media has either been silent or deliberately mis-informative as is their want. They have not told you the level which the struggle has reached in Southern Africa. They have not told you the amount of territory which has been liberated from the Portuguese in Angola, Guinea (Bissau), and Mozambique.

“Let no one have the impression that we are supporting a passive people.”

They have not told you that in 1970 there was a massive campaign by the Portuguese, a campaign to end all campaigns in Mozambique. It was designed to eliminate the liberated zones. It had a massive array of armaments, 50,000 troops, American advisers; they went to the United States and had one of their generals trained on the assumption that the United States are the world experts on counter-guerilla warfare. But even if I had to fight the counter-guerilla war, I would be reluctant to ask the advice of the Americans, because they are only experts in losing! It turned out that they lost that struggle — the people of the Mozambique today have a greater liberated area, have produced an intensification, not only of their military program, but of their socio-economic and political program.

The same applies in Angola, the same in Guinea (Bissau). And, furthermore, when we look at Southern Africa, although it is true that there are certain areas when the armed struggle, the highest level of struggle, has not yet been reached, we must not, for a movement deprecate the energies, the courage, and the activities of our Brothers and Sisters in that part of the world.

Let me say a brief word about South Africa. The people of South Africa are not cheap as some would have you believe. The people of South Africa have a long history of struggle, longer than in many other parts of the African continent. In the period after the first World War, there was in South Africa the strongest Black trade union on the Continent and in most parts of the world. The trade union known as the I.C.U., led by an African giant, Clement Sdale, was one of the greatest trade unions of its time. It failed! Why did it fail? Let me tell you a secret, it failed because it was betrayed by the white working class of South Africa.

“In the period after the first World War, there was in South Africa the strongest Black trade union on the Continent.”

Nevertheless, the struggle continues in South Africa. What happens in Southwest Africa (Namibia)? Few people know of Namibia. Namibia is the diamond mine of the world, that is where the Oppenheimers, the Goldfingers, the later Englehart, that is where the Rockefellers draft gem diamonds and industrial diamonds out of the ground by the tons every year.

And in Namibia, the people have had to face the brutality of the Germans in the last part of the 19th century and in the present century. Germany learned to practice fascism in Africa before it practiced it in Germany. It was against the heroic people of Namibia that the Germans unleashed a policy of genocide. Nevertheless, enough of the people, and this is a constant wonder — that we have managed to survive — to survive and to multiply — which amazed them (white people).

The people of Namibia last year staged a tremendous strike against the mining companies — out of the blue — no one expected it — the people of Namibia said to the mining companies, the white race’s international monopoly capitalist — they said, “We are still here! We are still here! And we will strike when the hour comes.” And this is true throughout Southern Africa.

In Zimbabwe, the whites thought they had a good thing going; they have banned Z.A.N.U., they banned Z.A.P.U. They have some in prison, the rest are exiled. They brought in the South African police and military. They have the support of the British government, they have the support of international monopoly capital, and they said, “We are going to stage a mock referendum which will draw the wool over the eyes of the world because we have intimidated the African sufficiently that we will get them to accept our domination by means of a referendum,” and then they attempted to count this referendum, they sent the British commission, and what happened? The people of Zimbabwe came out unarmed, unarmed mind you, to face the guns and they said, “no! no!” in a very loud voice; it was heard everywhere, it was unmistakable that they would not accept white minority rule in Zimbabwe.

“The people of Zimbabwe came out unarmed to face the guns and they said, ‘no! no!”’

And when you talk about struggle, furthermore, again it is to be remembered that there are governments in Africa today, who are putting their integrity, putting their existence out on the limb in order to support the struggle in South Africa. Governments like Tanzania, Zambia, Guinea, Algeria, and even the U.A.R., although it is fighting a war against the Zionists, they all have the time and resources to devote to the struggle of African unity and African liberation.

These are things to bear in mind when we say we are giving our support, because the world is full of many people who are claiming their rights but doing nothing else about it. We will support those who are claiming their rights and backing it up with what is necessary to demand and grasp one’s rights.

There is another illusion which must be squashed, and that is that when we support Africa, we are supporting a foreign entity, we are escaping from the struggle here, but the support of Africa is merely an extension from the struggle here.

The struggle is universal because the system of oppression is universal.

The struggle is international — and black unity must be international because we are the world’s most authentic international people. We live on every continent, through no choice of our own. But when the enemy has created a system of production and a system of exploitation which rests upon our physical presence in the Americas, in Europe, and in Africa, we will use that dispersed presence to mount a tremendous international campaign to liquidate the struggle that has reduced us to the position which we are in now.

“There are governments in Africa today who are putting their existence out on the limb in order to support the struggle in South Africa.”

Let me move toward a conclusion, Brothers and Sister, a conclusion which asks you to bear in mind what this gathering symbolizes. It symbolizes a “no” to Nixon, a “no” to the murderous policies in Vietnam, a “no” to the United States companies which are investing and exploiting on the African continent; a “no” to N.A.T.O. which provides Portugal with the wherewithal to bomb and blast our African Brother who are struggling for their rights in their own land. That must be an explicit “no”! It is also a “yes” — it is an affirmation, we are saying yes to the line which was developed by people like Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. DuBois, George Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Frantz Fanon.

We are saying “yes” to the struggle in Africa today which is led by such giants as Ahmed Sekou Toure, Julius Nyerere … And we are saying “yes” to people like the Soledad Brothers and the martyrs of Attica.

This time is a symbolic act of coming together. This is also a time for self analysis and self-criticism and rededication. So we will go from here with a new strength. We will reconsider the nature of the domestic struggle and its relation to the international struggle, moving toward the realization that the system must fall — it all must fall! Have no illusions about it, the system that was created within this country as it extends throughout the world is so immoral, so vicious that there is no compromise, there is no remedying — except to banish it!

So, we will move out, to contemplate in our various ways how to arrive at its destruction. As we move out, bear in mind a slogan which the Brothers in Southern Africa use. They say, “Victory or Death! Victory is Certain.” Victory or death because they are placing their lives on the line — the highest form of struggle! But they are saying “Victory is Certain” because we are the future, we are the repositories of the truth, we are the most exploited and the most oppressed _ and must, of necessity, by the repository of freedom. So let us join and reiterate that slogan of Southern Africa, “Victory or Death — Victory is Certain!”

(Crowd repeats: “Victory or Death — Victory is Certain!”). Power!

Walter Rodney, “The Meaning of African Liberation Day (a speech delivered May 27, 1972 in San Francisco, California),” transcribed and edited by Marvin X, Journal of Black Poetry 16 (Summer 1972), 5-9. Rodney’s speech also appeared in The East’s Black News (June 1, 1974). Black News reprinted it from Toronto’s Contrast newspaper. An excerpt was also published in Muhammed Speaks. The version that appears here was transcribed by and first published on Past and Future Present(s).

Editors, The Black Agenda Review

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com