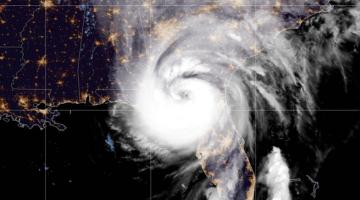

The island nations of the Caribbean are vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Their governments and people need action from those countries with the power to stop the impending catastrophe.

This article originally appeared in Tenement Yaad Media.

Since the 2020 storm season started, the Caribbean region has seen (perhaps) unprecedented downpours disrupt the daily lives of many communities and citizens. Even the most unorganized of cyclonic systems resulted in substantial damages* to infrastructure in Dominica, St. Lucia, Jamaica, Guadeloupe, Antigua & Barbuda, St. Kitts & Nevis, and Trinidad & Tobago. And yet, despite flooded streets, sweeping power outages, and buildings literally sliding off their foundations, many regional residents defer, if not decline, to act or adapt, even as the risks of these incidents increase. Almost entire governments, a plethora of private sector representatives, and a generous portion of the general public continue to operate as though these extreme weather events are within some familiar range of hurricane-adjacent horror, as opposed to reacting to the aforementioned incidents. It’s as if these events fail to serve as evidence of the existential crisis that is a change in global climate.

This is not intended to suggest that denial of climate change is a deep and pervasive issue in our region. In fact, engagement of Caribbean populations, via various research questionnaires, focus groups, and media outreach activities, implies that residents have at least a basic understanding of how a multitude of effects—ranging from air pollution events to Zika virus infections—might be attributable to variabilities in temperature and precipitation. A 2012 survey by the Planning Institute of Jamaica that probed the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral practices in Jamaica revealed that over 90% of persons had heard of climate change, over 70% were able to define the phenomenon, and almost 85% made some sufficiently clear connections between climate change and resulting impacts (such as tropical cyclones, sea level rise, and higher heat). My own dissertation and postdoctoral research (Whittaker and Bell, 2020) between 2015 and 2020 reflected comparable profiles of limited awareness and variable levels of comprehension and constrained agency among Eastern Caribbean residents with regard to climate change.

Rather, this commentary seeks to echo—because it bears repeating—the concerns regarding the incompleteness of climate change education and ultimately an absence of persons being empowered to adapt in the Caribbean. Regardless of any campaign or cause for transformation, it is certain that awareness and/or experience of a thing will simply not be enough. In the absence of adequate adaptation, inclusive of the implements of prevention (such as proper drainage in our increasingly concretized rainforests) and instruments of preparation (e.g. alternative energy sources), we regional residents are profoundly vulnerable to being victims of another flooding or Category 5 hurricane.

While I would not say there is comfort, there is arguably some encouragement to be regarded in the elevated visibility of our regional plight. Many Caribbean residents have recently witnessed and applauded our leaders, including Prime Minister (PM) of Antigua & Barbuda Gaston Brown and Prime Minister of Barbados Mia Mottley, deliver impassioned, somewhat rousing, but undoubtedly impressive speeches at separate United Nations (UN) events. They spoke to the harrowing realities of a Caribbean region vulnerable to and ultimately under-resourced to mitigate climate change effects. However, it is difficult to see any real-time (or even soon-come) accessible and tangible benefits of their presentations, especially if one is a psychologically-devastated farmer whose fields are desiccated by dry conditions or a nurse sweating through classic, barely-breathable, cotton-blend uniforms because the clinic lacks adequate air conditioning.

In addition, sustained commitments of local and global private sector partners notably have been sparse. This is unsurprising, given their enduring foundation on fossil fuel-driven economies and closed-circuit neoliberalist capitalist legacies. Does anyone really expect Mercedes-Benz in Jamaica or Kentucky Fried Chicken in Trinidad & Tobago or Sandals resort in St. Lucia to adopt corporate social responsibility practices built on aggressive, or even progressive, climate policies?

Moreover, there are the oft-competing priorities of our Caribbean leaders across their daily responsibilities to the fossil-fuel dependent industries tied to their governments. This makes it difficult to discern which leaders are genuine about their declarations to combat the effects of climate variability. One baffling example sees the aforementioned PM Mottley praise the prospects of a sustained partnership between the Caribbean cruise tourism industry and the region during a 2019 Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association conference. This was only a month after Hurricane Dorian devastated parts of the Bahamas... as if the cruise ship industry itself has not been a significant contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that drive global warming and thus spur climate change. Let me not even get started on the increasing chumminess between Jamaican PM Andrew Holness and China’s President Xi Jinping around infrastructure projects and trade deals. While the bilateral talks between the two nations aim to reduce the smaller state’s debt, the larger country rivals the U.S. and India for the title of world's most prolific polluter (for the #$%&ing love of BroGad!).

Now, perhaps our Caribbean heads-of-state are actually diligent, or at least mindful, in embedding some form of climate action in their approach to regional development. Perhaps one could make a good faith (benefit-of-the-doubt) argument for the mindfulness of our leaders (i.e they are catapulting their small Caribbean voices against the globe's industrial Goliaths), hoping the larger nations would at least stumble, causing some coins from their GDP to roll our way. But our vulnerabilities in the Caribbean are still profoundly our problem. The calls to action and invitations to provide aid embedded inside the high-level, international presentations of our Prime Ministers might easily fall on defiant ears (which they already might have). Or our leaders’ pleas/petitions might actually be heard, but go unheeded, due to the fiscal constraints of their UN “partners” (as is partly the case per the current economic ravages of COVID-19 worldwide). How then, without the financial and technical support of our usual benefactors, is the Caribbean supposed to successfully and sustainably respond to climate change, a feat that Nevis Premier Mark Brantley often frames—somewhat cryptically, but provocatively—as “[the] Caribbean... being asked to cash a [check] it did not write”?

For the question “If we are truly or mostly alone in this, what can we even do?” the answers are elusive, if at all there are appropriate ones. But this is not a reason to despair or to be passive or to recline into a submissive position. While it is unsettling that the majority of respondents of the aforementioned surveys in Jamaica and St. Kitts & Nevis report feeling that their governments are not doing enough, or even anything about climate change, there is opportunity in their less-than-optimistic perspectives

For starters, this presents a chance for those responsible for governance in the Caribbean to be more open and direct about plans and projects to adapt to climate change impacts. Additionally, if Caribbean leaders further leverage the reach of national emergency management agencies and use appropriate media (e.g. brief, easily digestible, digital content), the majority of residents will be able to participate in dialogues about their capacity and roles in managing climate change effects.

Also, without denouncing or devaluing the contributions of awareness campaigns, we as Caribbean stakeholders must admit that—amid this time of high heat and heavy rainfalls wreaking havoc—research, reports, speeches, slide presentations, posters, pamphlets, and one-off school programs are but diagnoses of vulnerabilities to long-suffering people who need clear and appropriate prescriptions, funds to access what is prescribed, and pharmacies to fill/fulfill those scripts. Even if local, regional, or global partners are unreliable in honoring their debts to the people and environments adversely affected by their irresponsible disaster-inducing actions, we must act and adapt as much as we can. We must demand that authorities and community partners in our respective countries make easier access to formalized and equitably-enforced protective services (e.g. shelters for women and/or LGBTQ+ people forced to stay-in-place during extreme weather events). We must insist on access to regular and subsidized procurement of restorative goods (e.g. mosquito nets, tarpaulins, and cooling technologies powered by renewable energy). We must see beyond our individual fiscal and material deficits to entreat entities with political and commercial power to consider and deliver on ideas, designs, and programs tailored to increase the Caribbean’s capacities in the increasing intense conflict with climate change impacts.

Ultimately, when it comes to the Caribbean's response to and ultimately survival of climate change, it is no longer enough to have knowledge, experience, or even an opinion on what is coming. It is insufficient simply to prepare for “bad weather” in the same way our predecessors did, especially as worse weather is already here and happening. If we are to stay connected to any viable, safe and secure future, we must work to break the strength of the connection between climate-change-induced disasters and the detrimental environmental effects by actively inserting ourselves with data-driven, innovative interventions (with the caveat that some nations are more ready than others to do so using technology) for the sake of ourselves and those who are to come.

So said. Not so easily done. But do it we must! Caribbean lives now, and soon-to-come, are at stake.

Sources:

Planning Institute of Jamaica (2012). Report on Climate Change Knowledge, Attitude and Behavioural Practice Survey. Kingston, Jamaica, Caribbean Institute of Media and Communication Knowledge.

Whittaker, S. D. and Bell, M. L. (2020), Climate Change Effects on Health Access and Perceptions in the Caribbean (Unpublished).

About the Tenants

Steve D. Whittaker PhD is a self-described “perpetual scholar” - ever-committed to learning more about and alongside others. He is a writer, graphic artist, global health researcher, educator, environmental scientist, statistician and 3-time Yale survivor. He provides technical assistance to climate change adaptation and education training activities in the Caribbean, most recently with the Holistic Education Research and Conservation (HERC) group in St. Kitts & Nevis. He is also an eternal consumer and curator of Caribbean culture, literature lover, and people-watcher. His favorite color is blue (for now), despite his daughter’s best and long-time lobbying for the unmatched prettiness of purple or pink. You can find Dr. Whittaker on twitter @JusDuWhit

Sherine Andreine Powerful, MPH is a Doctor of Public Health candidate at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. As a Black Caribbean Feminist, she is committed to celebrating and furthering pleasure, healing, and liberation for Black, Brown, and Indigenous peoples and persons of diverse a/genders and a/sexualities, centering those from the Caribbean. Her present interests include feminist global health and development; gender and sexual health, equity, and justice; and resilience and anticolonial sustainable development in the context of climate change.