The phrase racial capitalism first emerged in the context of the anti-Apartheid and southern African liberation struggles in the 1970s.

“Cedric Robinson neither invented nor coined ‘racial capitalism.’”

The phrase “racial capitalism” is suddenly everywhere. Not so long ago it was a largely obscure, academic term. It was often dismissed as being inherently redundant (capitalism is always racist), or irrelevant (capitalism is not racist), or simply misguided (racism is not the issue, the issue is capitalism). Recently, however, and certainly enabled by the unmasked and uncompromised racist and class politics of the Trump years, racial capitalism is often and easily evoked. It has become the regular stand-in for any analysis of any incident or institution where race and class are seen to intersect.

Yet ubiquity has led to analytical emptiness. Often the phrase racial capitalism is evoked without being adequately explained. Sometimes racial capitalism is named without being described. Moreover, the origins of the phrase racial capitalism have also become obscured, if not erased. Most people who use the phrase assert that the late African American political theorist Cedric Robinson “invented” or “coined” the term racial capitalism. Certainly, Robinson’s book Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, first published in 1983 and then re-issued in 2000, has been incredibly important in popularizing the term. Yet Robinson neither invented nor coined “racial capitalism.” In fact, the term had circulated for many years before Robinson first used it. These older invocations of “racial capitalism” are incredibly important. They are important not simply for mere academic reasons. They clarify the significant political and analytical interventions racial capitalism was meant to make. Not only do they demonstrate that capitalist exploitation and racism were linked, they also show how both capitalism and racism are historical formations that are underwritten by settler colonialism, apartheid state formation, and imperialism.

“Often the phrase racial capitalism is evoked without being adequately explained.”

The phrase racial capitalism first emerged in the context of the anti-Apartheid and southern African liberation struggles in the 1970s. Racial capitalism was used by activists and writers, many aligned with the Black Consciousness Movement. They rejected liberal analyses that believed the racial inequalities of Apartheid could be reformed through the organization of a better capitalism, and they were critical of Marxist analyses that insufficiently attended to questions of race. At the same time, the use of racial capitalism became a way of bringing a stronger class analysis into the vocabularies of Black Consciousness. We see, then, powerful deployments of the term “racial capitalism” in Martin Legassick and David Hemson’s pamphlet Foreign Investment and the Reproduction of Racial Capitalism in South Africa (1976), in the work of Africana Studies professor James A. Turner’s research on US investment in South Africa in the Western Journal of Black Studies (1976), in Barnard Magubane's attacks on liberal analysis of the South African situation in the Reviewof the Fernand Braudel Center (1977), and in John S. Saul and Stephen Gelb’s trenchant analysis of the crisis in South Africa in The Monthly Review (1981). Neither Cedric Robinson nor his latter-day interlocutors engage with this African research on racial capitalism. However, it must also be stated that Robinson’s engagement with Africa is perfunctory, at best.

“They rejected liberal analyses that believed the racial inequalities of Apartheid could be reformed through the organization of a better capitalism, and they were critical of Marxist analyses that insufficiently attended to questions of race.”

Among the most important figures using the term racial capitalism in the South African context was Neville Alexander. Alexander was an activist and educator from the Eastern Cape who had been imprisoned on Robben Island because of his anti-apartheid activities. Alexander had long grappled with questions of race, class, ethnicity, and nation in South Africa, as evidenced by his book One Azania, One Nation: The National Question in South Africa (1979), written under the pseudonym No Sizwe and heavily influenced by the sociologist Oliver Cromwell Cox, among others. In his address to the annual meeting of the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO) in December 1982, Alexander spoke of the crisis of racial capitalism in South Africa, naming the white middle classes as its beneficiaries. But Alexander’s enduring contribution to the theory of racial capitalism came from “Nation and Ethnicity in South Africa,” his address to the 1983 National Forum meeting in Hammanskrall, a town near Pretoria. Spurred by a call by Black Consciousness activists, the National Forum brought together some 200 organizations and some 800 delegates, most of whom were to the left of the African National Congress and who saw the ANC’s Freedom Charter as a compromised, liberal document. At the end of the conference, delegates unanimously adopted the Manifesto of the Azanian People; its opening sentences are drawn from Alexander’s talk.

“The immediate goal of the national liberation struggle now being waged in South Africa is the destruction of the system of racial capitalism,” Alexander writes. “Apartheid is simply a particular socio-political expression of this system. Our opposition to apartheid is therefore only a starting point for our struggle against the structures and interests which are the real basis of apartheid.” His address continues with an analysis of the historical organization of the Apartheid state and the transformation of racism from ideology to policy; an extended discussion of the mobilization of ideas of race, ethnicity, and nation within both ruling party and liberal critiques; and an argument for the importance of language and culture in national liberation struggles. Alexander looks beyond South Africa, evoking the work of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) and the struggle for liberation in Mozambique as an example of how South African should move forward. He also makes an assertive statement on the role of Black working class in any conception of South African liberation. “The black working class has to act as a magnet,” he writes, “that draws all the other oppressed layers of our society, organizes them for the liberation struggle, and imbues them with the consistent democratic socialist ideas which alone spell death to the system of racial capitalism as we know it today.”

Since the end of Apartheid, the use of racial capitalism in South Africa has declined. Yet, arguably, given the conditions of the Black working class, its analytical force remains, both in South Africa and globally. Below, we reproduce in full Alexander’s “Nation and Ethnicity in South Africa.”

Charisse Burden-Stelly

Peter James Hudson

Jemima Pierre

Editors, The Black Agenda Review

Nation and Ethnicity in South Africa

Neville Alexander

This address was delivered at the first National Forum meeting on 11 June 1983 at St/ Peter’s Conference Centre in Hammanskraal, South Africa. It appeared in the National Forum’s bulletin on the conference and was republished in the South African journals Work In Progress (1983) and Frank Talk (1984).

The immediate goal of the national liberation struggle now being waged in South Africa is the destruction of the system of racial capitalism. Apartheid is simply a particular socio-political expression of this system. Our opposition to apartheid is therefore only a starting point for our struggle against the structures and interests which are the real basis of apartheid.

In South Africa, as in any other modern capitalist country, the ruling class consists of the owners of capital which is invested in mines, factories, land, wholesaling and distribution networks and banks. The different sections of the ruling class often disagree about the best methods of maintaining or developing the system of ‘free enterprise’, as they call the capitalist system. They are united, however, on the need to protect the system as a whole against all threats from inside and outside the country.

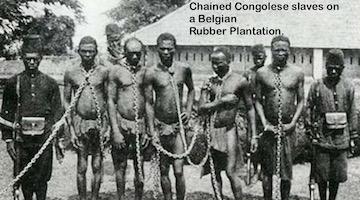

During the past hundred odd years, a modern industrial economy has been created in South Africa under the spur of the capitalist class. The most diverse groups of people (European settlers, immigrants, African and East Indian slaves, Indian and Chinese indentured labourers and indigenous African people) were brought together and compelled to labour for the profit of the different capitalist owners of the means of production.

Now, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Western and Central Europe, roughly similar processes had taken place. But there was one major difference between Europe and the colonies of Europe. For in Europe, in the epoch of the rise of capitalism, the up and coming capitalist class had to struggle (together with and in fact on the backs of the downtrodden peasantry and the tiny class of wage workers) against feudal aristocracy in order to be allowed to unfold their enterprise. Through unequal taxation, restrictions on freedom of trade and freedom of movement and in a thousand different ways the aristocracy exploited the bourgeoisie and the other toiling classes.

In order to gain the benefit of their labours, to free the rapidly developing forces of production from the fetters of feudal relations of production, the capitalist class had to organize the peasants and the other urban classes to overthrow the feudal system. In the course of these struggles of national unification this bourgeoisie developed a nationalist democratic ideology and its cultural values and practices became the dominant ones in the new nations. The bourgeoisie became the leading class in the nation and were able to structure it in accordance with their class interests.

In the twentieth century in the colonies of Europe, however, the situation has been and is entirely different. In these colonies, European or metropolitan capitalism (imperialism) had become the oppressor who brutally exploited the colonial peoples. In some cases the colonial power had allowed or even encouraged a class of colonial satellite capitalists to come into being. This class, being completely dependent on London, Paris, Brussels, Berlin or New York, could not oppose imperialism in any consistent manner. If it had done so it would in effect have committed class suicide because it would have had to advocate the destruction of the imperialist-capitalist system which is the basis of colonial oppression. After World War II, especially, the imperialist powers realised that this situation (backed up by the existence and expansion of the Soviet system) would put a great strain on the capitalist system as a whole. Consequently, we had a period of ‘decolonisation’ which as we now know merely ushered in the present epoch of neo- colonialism which Kwame Nkrumah optimistically called the ‘last stage of imperialism’.

In South Africa, a peculiar development took place. Here, the national bourgeoisie had come to consist of a class of white capitalists. Because they could only farm and mine gold and diamonds profitably if they had an unlimited supply of cheap labour, they found it necessary to create a split labour market – one for cheap black labour and one for skilled and semi-skilled (mainly white) labour. This was made easier by the fact that in the pre-industrial colonial period white-black relationships had been essentially master-servant relations. Racialist attitudes were therefore prevalent in one degree or another throughout the country. In order to secure their labour supply as required, the national bourgeoisie in South Africa had to institute and perpetuate the system whereby black people were denied political rights, were restricted in their freedom of movement, tied to the land in so-called ‘native reserves’, not allowed to own landed property anywhere in South Africa and their children given an education, if they received any at all, that ‘prepared them for life in a subordinate society’. Unlike their European predecessors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the colonial national bourgeoisie in South Africa could not complete the bourgeois democratic revolution. They compromised with British imperialism in 1910 in order to maintain their profitable system of super-exploitation of black labour.

They did not incorporate the entire population under the new state on the basis of legal equality, they could not unite the nation. On the contrary, ever since 1910, elaborate strategies have been evolved and implemented to divide the working people into ever smaller potentially antagonistic groups. Divide and rule, the main policy of any imperial power, has been the compass of every government of South Africa since 1910.

In order to justify these policies the ideology of racism was elaborated, systematised and universalised. People were born into a set-up where they were categorised ‘racially’. They grew up believing that they were ‘Whites’, ‘Coloureds’, ‘Africans’, ‘Indians’. Since 1948, they have been encouraged and often forced to think of themselves in even more microscopic terms as ‘Xhosa’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Malay’, ‘Muslim’, ‘Hindu’, ‘Griqua’, ‘Sotho’, ‘Venda’, etc. To put it differently: at first the ruling ideology decreed that the people of South Africa were grouped by god into four ‘races’. The ideal policy of the conservative fascist-minded politicians of the capitalist class was to keep these ‘races’ separate. The so-called liberal element strove for ‘harmonious race relations in a multi-racial country’. Because of the development of the biological sciences where the very concept of ‘race’ was questioned and because of the catastrophic consequences of the racist Herrenvolk policies of Hitler Germany, socio-political theories based on the concept of ‘race’ fell into disrepute. The social theorists of the ruling class then resorted to the theory of ‘ethnic groups’, which had in the meantime become a firmly established instrument of economic and political policy in the United States of America as well as elsewhere in the world. It is to be noted that this theory of ethnicity continued to be based on the ideology of ‘race’ as far as South Africa was concerned. From the point of view of the ruling class, however, the theory of ‘ethnic groups’ was a superior instrument of policy because, as I have pointed out, it could explain and justify even greater fragmentation of the working people whose unity held within itself the message of doom for the capitalist apartheid system in this country.

The fact of the matter is that the Afrikaner National Party used ethnic theories in order to justify bantustan strategy whereby it created bogus ‘nations’ and forced them to accept an illusory ‘independence’ so that the working class would agitate for political rights in their own so-called ‘homeland’.

The idea, as we all know, was to create, revive and entrench antagonistic feelings of difference between language groups (Xhosa, Zulu, Sotho, Tswana, etc.), religious groups (Muslim, Hindu, Christian, etc.), ‘cultural’ groups (Griqua, Malay, Coloured, etc.), and of course ‘racial’ groups (African, Coloured, Indian, White, etc.). I need not show here how this theory was designed to serve the interests of the ruling class by preserving apartheid (grand and petty) and how ruthlessly it was applied. The literature on apartheid is so large today that no single person could study all of it in the span of one lifetime. What we need to do is to take a careful, if brief, look at how the liberation movement has conceived of the differences between and the unity of the officially classified population registration groups, the different language groups and religious sects that constitute our single nation.

Multi-racialism, non-racialism and anti-racism

Those organizations and writers within the liberation movement who used to put forward the view that South Africa is a multi-racial country composed of four ‘races’ no longer do so for the same reasons as the conservative and liberal ruling-class theorists. They have begun to speak more and more of building a ‘non-racial’ South Africa. I am afraid to say that for most people who use this term ‘non-racial’ it means exactly the same thing as multi-racial. They continue to conceive of South Africa’s population as consisting of four so-called ‘races’. It has become fashion-able to intone the words a ‘non-racial democratic South Africa’ as a kind of open sesame that permits one to enter into the hallowed portals of the progressive ‘democratic movement’. There is nothing wrong with the words themselves. But, if we do not want to be deceived by words we have to look behind them at the concepts and the actions on which they are based.

The word ‘non-racial’ can be accepted by a racially oppressed people if it means that we reject the concept of ‘race’, that we deny the existence of ‘races’ and thus oppose all actions, practices, beliefs and policies based on the concept of ‘race’. If in practice (and in theory) we continue to use the word non-racial as though we believe that South Africa is inhabited by four so-called ‘races’, we are still trapped in multi-racialism and thus in racialism. Non-racialism, meaning the denial of the existence of races, leads on to ‘anti-racism’ which goes beyond it because the term not only involves the denial of ‘race’ but also opposition to the capitalist structures for the perpetuation of which the ideology and theory of ‘race’ exist. Words are like money. They are easily counterfeited and it is often difficult to tell the real coin from the false one. We need, therefore, at all times to find out whether our non-racialists are multi-racialists or anti-racists. Only the latter variety can belong in the national liberation movement.

Ethnic groups, national groups and nations

The theory of ethnicity and of ethnic groups has taken the place of theories of ‘race’ in the modern world. Very often ‘racial’ theories are incorporated in ‘ethnic theories’. In this paper, I am not going to discuss the scientific validity of ethnic theory usually called pluralism of one kind or another. That is a job that one or more of us in the liberation movement must do and do very soon before our youth get infected incurably with these dangerous ideas at the universities. All that I need to point out here is that the way in which the ideologues of the National Party use the term ‘ethnic group’ makes it almost impossible for any serious-minded person grappling with these problems to use the term as a tool of analysis.

It has been shown by a number of writers that the National Party’s use of the terminology of ethnicity is contradictory and designed simply to justify the apartheid/bantustan policies. Thus, for example, they claim amongst other things that:

· The ‘African’ people consist of between eight and ten different ‘ethnic groups’, all of whom want to attain ‘national’, i.e. bantustan, ‘independence’.

· The ‘coloured’ people consist of at least three different ‘ethnic groups’ (Malay, Cape Coloured, Griqua and possibly ‘other Coloured’). On the other hand, ‘Coloureds’ are themselves an ethnic group, but not a ‘nation’.

· The ‘Indian’ people constitute an ethnic group as do people of Chinese origin, but these are not ‘nations’.

· The ‘white’ people consist of Afrikaans, English and other ethnic groups but constitute a single nation, the white nation of South Africa.

· In all this tangle of contradictions, the most important point is that every ‘ethnic group’ is potentially a so-called ‘nation’ unless it is already part of a ‘nation’ as in the case of the whites.

We have to admit that in the liberation movement ever since 1896, the question of the different population registration groups has presented us with a major problem, one which was either glossed over or evaded or simply ignored. I cannot go into the history of the matter here. We shall have to content ourselves with the different positions taken up by different tendencies in the liberation movement today. These can be summarised briefly as falling into three categories:

(1)For some, the population registration groups are ‘national groups or racial groups, or sometimes ethnic groups’. The position of these people is that it is a ‘self-evident and undeniable reality that there are Indians, Coloureds, Africans and Whites (national groups) in our country. It is a reality precisely because each of these national groups has its own heritage, culture, language, customs and traditions’ (Zak Yacoob, speech presented at the first general meeting of the Transvaal Indian Congress on 1 May 1983).

Without debating the point any further, let me say that this is the classical position of ethnic theory. I shall show presently that the use of the word ‘national group’ is fraught with dangers not because it is a word but because it gives expression to and thereby reinforces separatist and disruptive tendencies in the body politic of South Africa. The advocates of this theory outside the liberation movement, such as Inkatha and the PFP, draw the conclusion that a federal constitutional solution is the order of the day. Those inside the liberation movement believe contradictorily that even though the national groups with their different cultures will continue to exist they can somehow do so in a unitary state as part of a single nation.

We have to state clearly that if things really are as they appear to be we would not need any science. If the sun really quite self-evidently moved around the earth we would not require astronomy and space research to explain to us that the opposite is true, that the ‘self-evidently real’ is only apparent. Of course there are historically evolved differences of language, religion, customs, job specialisation, etc. among the different groups in this country. But we have to view these differences historically, not statically. They have been enhanced and artificially engendered by the deliberate ruling-class policy of keeping the population registration groups in separate compartments, making them lead their lives in group isolation except in the marketplace. This is a historical reality. It is not an unchanging situation that stands above or outside history. I shall show just now how this historical reality has to be reconciled through class struggle with the reality of a single nation.

The danger inherent in this kind of talk is quite simply that it makes room both in theory and in practice for the preaching of ethnic separatism. It is claimed that a theory of ‘national groups’ advocated in the context of a movement for national liberation merely seeks to heighten the positive features of each national group and to weld these together so that there arises out of this process or organization a single national consciousness. (Yacoob), whereas the ruling class ‘relying upon the negative features’ of each national group ‘emphasises ethnicity’ or ‘uses culture in order to reinforce separation and division’. We can repeat this kind of intellectualistic solace until we fall asleep, the fact remains that ‘ethnic’ or ‘national group’ approaches are the thin edge of the wedge for separatist movements and civil wars fanned by great-power interests and suppliers of arms to opportunist ‘ethnic leaders’. Does not Inkatha in some ways represent a warning to all of us? Who decides what are the ‘positive features’ of a national group? what are the boundaries or limits of a national group? Are these determined by the population register? Is a national group a stunted nation, one that, given the appropriate soil, will fight for national self-determination in its own nation-state? Or does the word ‘national’ have some other more sophisticated meaning?

These are relevant questions to ask because the advocates of the four-nation or national-group approach maintain that a liberated South Africa will guarantee group rights such as ‘the right of national groups to their culture’ and that ‘we have to accept that if the existence of national groups is a reality and if each national group has its own culture, traditions, and problems, the movement for change is best facilitated by enabling organization around issues which concern people in their daily lives, issues such as low wages, high transport costs and poor housing’. Or, as other representatives of this tendency have bluntly said, we need separate organizations for each of the national groups, which organizations can and should be brought together in an alliance.

These are weighty conclusions on which history itself (since 1960 and especially since 1976) has pronounced a negative judgement. To fan the fires of ethnic politics today is to go backwards, not forward. It plays into the hands of the reactionary middle-class leadership. It is a reactionary, not a progressive policy from the point of view of the liberation movement taken as a whole. Imagine us advocating ‘Indian’, ‘Coloured’, and ‘African’ trade unions or student unions today!

(2) There is a diametrically opposite view within the liberation movement even though it is held by a very small minority of people. According to this view, our struggle is not a struggle for national liberation. It is a class struggle pure and simple, one in which the ‘working class’ will wrest power from the ‘capitalist class’.

For this reason, the workers should be organized regardless of what so-called group they belong to. This tendency seems to say (in theory) that the historically evolved differences are irrelevant or at best of secondary importance.

I find it difficult to take this position seriously. I suspect that in practice the activists who hold this view are compelled to make the most acrobatic compromises with the reality of racial prejudice among ‘workers’. To deny the reality of prejudice and perceived differences, whatever their origin, is to disarm oneself strategically and tactically. It becomes impossible to organize a mass movement outside the ranks of a few thousand students perhaps.

Again, the historical experience of the liberation movement in South Africa does not permit us to entertain this kind of conclusion. All the little organizations and groups that have at one time or another operated on this basis have vanished after telling their simple story which, though ‘full of sound and fury’, signified nothing.

(3) The third position is one that has been proved to be correct by the history of all successful liberation struggles in Africa and elsewhere. I have found no better description of this position than that outlined by President Samora Machel in a speech held in August 1982 in reply to General Malan’s accusations that South Africa was being ‘destabilised’ by hostile elements in the sub-continent.

In that speech, Machel said amongst other things that:

Our nation is historically new. The awareness of being Mozambicans arose with the common oppression suffered by all of us under colonialism from the Rovuma to the Maputo. Frelimo, in its twenty years of existence and in this path of struggle, turned us progressively into Mozambicans, no longer Makonde and Shangane, Nyanja and Ronga, Nyungwe and Bitonga, Chuabo and Ndau, Macua and Xitsua. Frelimo turned us into equal sons of the Mozambican nation, whether our skin was black, brown or white.

Our nation was not moulded and forged by feudal or bourgeois gentlemen. It arose from our armed struggle. It was carved out by our hard-working calloused hands.

Thus during the national liberation war, the ideas of country and freedom were closely associated with victory of the working people. We fought to free the land and the people. This is the reason that those, who at the time wanted the land and the people in order to exploit them, left us to go and fight in the ranks of colonialism, their partner. The unity of the Mozambican nation and Mozambican patriotism is found in the essential components of, and we emphasise, anti-racism, socialism, freedom and unity. (WIP, No. 26)

This statement is especially significant when one realises that for many years Frelimo accepted that ‘there is no antagonism between the existence of a number of ethnic groups and national unity’. This sentence comes from a Frelimo document entitled ‘Mozambican Tribes and Ethnic Groups: Their Significance in the struggle for National Liberation’. It was written at a time ‘when the movement actually was under strong pressure from politicians who were consciously manipulating ethnicity in their own interest’ (J Saul, The Dialectic of Class and Tribe).

Even earlier in 1962 a Frelimo document had stressed that it is true that:

there are differences among us Mozambicans. Some of us are Makondes, others are Nyanjas, others Macuas, etc. Some of us come from the mountains, others from the plains. Each of our tribes has its own language, its specific uses and habitudes and different cultures. There are differences among us. This is normal ... In all big countries there are differences among people.

All of us Mozambicans – Macuas, Makondes, Nyanjas, Changans, Ajuas, etc. – we want to be free. To be free we have to fight united. All Mozambicans of all tribes are brothers in the struggle. All the tribes of Mozambique must unite in the common struggle for the independence of our country.

The development of the Mozambican national liberation ideology through the lessons learnt in struggle is shown clearly by President Machel’s August 1982 statement that

Ours is not a society in which races and colours, tribes and regions coexist and live harmoniously side by side. We went beyond these ideas during a struggle in which we sometimes had to force people’s consciousness in order for them to free themselves from complexes and prejudices so as to become simply, we repeat, simply people.

Every situation is unique. The experience of FRELIMO, while it may have many lessons for us, cannot be duplicated in South Africa. Certainly the population registration groups of South Africa are neither ‘tribes’ nor ‘ethnic groups’ nor ‘national groups’. In sociological theory, they can be described as colour castes or more simply as colour groups. So to describe them is not unimportant since the word captures the nature or the direction of development of these groups. But the question of words is not really the issue. What is important is to clarify the relationship between class, colour, culture and nation.

The economic, material, language, religious and other differences between colour groups are real. They influence and determine the ways in which people live and experience their lives. Reactionary ethnic organization would not have been so successful in the history of this country had these differences not been of a certain order of reality. However, these differences are neither permanent nor necessarily divisive if they are restructured and redirected for the purposes of national liberation and thus in order to build the nation. The ruling class has used language, religious and sex differences among the working people in order to divide them and to disorganize them. Any organization of the people that does not set out to counteract these divisive tendencies set up by the ruling-class strategies merely ends up by reinforcing these strategies. The cases of Gandhi or Abdurrahman are good examples. Middle-class and aspiring bourgeois elements quickly seize control of such colour-based ‘ethnic’ organizations and use them as power bases from which they try to bargain for a larger share of the economic cake. This is essentially the kind of thing that the bantustan leaders and the bantustan middle classes are doing today.

Because they are oppressed, all black people who have not accepted the rulers’ bantustan strategy desire to be free and to participate fully in the economic, political and social life of Azania. We have seen that the national bourgeoisie have failed to complete the democratic revolution. The middle classes cannot be consistent since their interests are, generally speaking and in their own consciousness, tied to the capitalist system. Hence only the black working class can take the task of completing the democratisation of the country on its shoulders. It alone can unite all the oppressed and exploited classes. It has become the leading class in the building of the nation. It has to redefine the nation and abolish the reactionary definitions of the bourgeoisie and of the reactionary petty bourgeoisie. The nation has to be structured by and in the interests of the black working class. But it can only do so by changing the entire system. A non-racial capitalism is impossible in South Africa. The class struggle against capitalist exploitation and the national struggle against racial oppression become one struggle under the general command of the black working class and its organizations. Class, colour and nation converge in the national liberation movement.

Politically in the short term and culturally in the long term the ways in which these insights are translated into practice are of the greatest moment. Although no hard and fast rules are available and few of them are absolute, the following are crucial points in regard to the practical ways in which we should build the nation of Azania and destroy the separatist tendencies amongst us.

(1)Political and economic organizations of the working people should as far as possible be open to all oppressed and exploited people regardless of colour.

While it is true that the Group Areas Act and other laws continue to concentrate people in their organizations – geographically speaking – largely along lines of colour, it is imperative and possible that the organizations themselves should not be structured along these lines. The same political organizations should and can function in all the ghettoes and group areas, people must and do identify with the same organizations and not with ‘ethnic’ organizations.

(2) All struggles (local, regional and national) should be linked up. No struggle should be fought by one colour group alone. The President’s Council proposals, for example, should not be analysed and acted upon as of interest to ‘Coloureds’ and ‘Indians’ only. The Koornhof Bills should be clearly seen and fought as affecting all the oppressed and exploited people.

(3) Cultural organizations that are not locally or geographically limited for valid community reasons should be open to all oppressed and exploited people.

The songs, stories, poems, dances of one group should become the common property of all even if their content has to be conveyed by means of different language media. In this way, and in many other ways, by means of class struggle on the political and on the cultural front, the cultural achievements of the people will be woven together into one Azanian fabric. In this way we shall eliminate divisive ethnic consciousness and separatist lines of division without eliminating our cultural achievements and cultural variety. But it will be experienced by all as different aspects of one national culture accessible to all. So that, for example, every Azanian child will know – roughly speaking – the same fairy tales or children’s stories, whether these be of ‘Indian’, ‘Xhosa’, ‘Tswana’, ‘German’ or ‘Khoikhoi’ origin.

(4) The liberation movement has to evolve and implement a democratic language policy not for tomorrow but for today. We need to discuss seriously how we can implement – with the resources at our disposal – the following model which, to my mind, represents the best possible solution to the problem of communication in Azania. All Azanians must have a sound knowledge of English whether as home language or as second language.

All Azanians must have a conversational knowledge of the other regionally important languages. For example, in the Eastern Province every person will know English; Afrikaans-speaking persons will have a conversational knowledge of Xhosa and Xhosa-speaking persons will have a conversational knowledge of Afrikaans. In an area like Natal, a knowledge of English and Zulu would in all probability suffice.

These are sketchy ideas that have to be filled in through democratic and urgent discussion in all organizations of the people and implemented as soon as we have established the necessary structures and methods.

The historic role of the black working class

The black working class is the driving force of the liberation struggle in South Africa. It has to ensure that the leadership of this struggle remains with it if our efforts are not to be deflected into channels of disaster. The black working class has to act as a magnet that draws all the other oppressed layers of our society, organizes them for the liberation struggle and imbues them with the consistent democratic socialist ideas which alone spell death to the system of racial capitalism as we know it today.

In this struggle the idea of a single nation is vital because it represents the real interest of the working class and therefore of the future socialist Azania. ‘Ethnic’, national group or racial group ideas of nationhood in the final analysis strengthen the position of the middle class or even the capitalist oppressors themselves. I repeat, they pave the way for the catastrophic separatist struggles that we have witnessed in other parts of Africa. Let us never forget that more than a million people were massacred in the Biafran war, let us not forget the danger represented by the ‘race riots’ of 1949. Today, we can choose a different path. We have to create an ideological, political and cultural climate in which this solution becomes possible.

I believe that if we view the question of the nation and ethnicity in this framework we will understand how vital it is that our slogans are heard throughout the length and breadth of our country.

One People, One Azania!

One Azania, One Nation!

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com