The Artibonite Valley, the heart of the country’s rice production, has been in terminal crisis since the 1990s. Photo: Lautaro Rivara

The author unpacks the tired trope of “poor rich Haiti,” highlighting the role of foreign capital and local elites in the destruction of life in the countryside.

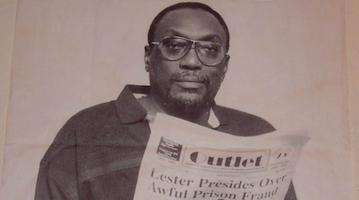

“Jovenel Moïse has made the northeast region his personal fiefdom.”

Does the oft-repeated refrain that “Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere” explain anything? Is it a poor country or an impoverished country? Or perhaps it is unsuspectedly rich? Are its indifferent friends in the West really not interested in the country? Why then do the United States and European countries seem to be so zealous about the “Haitian thing”? In a series of notes and based on fieldwork carried out in four departments of the country, we will focus on understanding the “poor rich Haiti” and some of the initiatives of what has been called its “reconstruction” since 2010. We will discuss the economic interests of Western powers, expressed through initiatives such as industrial parks, mining operations, enclave tourism ventures, land grabbing and agricultural free zones.

Haiti’s borders are curious. The small country is bordered to the east by the Dominican Republic, dividing in two the territory of the island of Hispaniola. To the west it borders the Caribbean Sea and to the south, a forgotten maritime border with the Republic of Colombia. But what interests us here is a border that is not entirely imaginary: to the north and northeast, although the maps would like to indicate otherwise, Haiti borders the United States.

It is here, in this region, that most US economic interests – and also those of its smaller partners – are concentrated. This is the case of Canada, that peculiar North American colony that in turn colonizes others. But also those of France, Germany and other European nations. In this and the following notes, we will talk about industrial parks, mining and speculation, enclave tourism ventures, land grabbing and agricultural free trade zones. This does not include some unholy initiatives in other parts of the country, such as the seizure of entire islands, drug trafficking or tax havens where the money comes in dirty and goes out free of guilt and sin.

But it is in the northeast region of this “poor rich” country that the power enjoyed by the current de facto president, Jovenel Moïse, has been amassed. He has made this territory his personal fiefdom. His modus operandi has been land grabbing and the true foundation of his power, his economic alliances with transnational capital, both legal and extralegal.

For this, we will travel to the heart of the communities affected by what, after the devastating earthquake of 2010, has become known as the “Reconstruction of Haiti.” In this first note, we will talk – paraphrasing Eduardo Galeano – about the “Banana King” Jovenel Moïse and his numerous agricultural courtiers. But first, let’s take a look at the situation of the rural areas and the local peasantry.

Barefoot

One out of every two inhabitants of the country lives in the countryside. But an even higher percentage of the population, around 66%, depends on and subsists in relation to rural areas and agricultural production. According to a study by the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the urban population has only overtaken the rural population in the last five years, and the current difference is only about 100,000 people.

Land everywhere is finite and vital. But it is even more so in a territory covered by extensive mountain ranges, and where the agricultural frontier is receding with every meter gained by deforestation and desertification – today the country retains barely 2 percent of its original vegetation cover. It is not surprising, then, that a large part of the peasant population is poor: they are the so-called pyè atè, the “pata en tierra,” the barefoot.

For a long time, however, an unprecedentedly radical measure was at least able to guarantee Haitians a piece of land on which to produce and reproduce life. Since the revolutionary constitution of 1805, land ownership was denied to foreigners on the grounds of sovereignty and national dignity, becoming an obstacle to the full implementation of capitalism on the island. At least until the definitive abolition of this prohibition in 1915, under the mantle of the American occupation.

Today, there are around 600,000 farms in Haiti, organized in small plots – jaden – of between 0.5 and 1.8 hectares. Peasant agriculture is mostly family and traditional, but there are many different forms of land ownership, work and usage: family landowners, tenant farmers, day laborers, sharecroppers, etc. The tools used are rustic, often no more than the traditional pickaxe and machete, usually without draft animals, without any kind of machinery, without chemical fertilizers, with native seeds, all under a rain-fed agricultural regime. Despite the enormous contribution of peasant agriculture to national wealth – around 25 percent of GDP – the state’s contributions to the sector are practically nonexistent.

On the other side of rural life, a select group of families, usually living abroad, as well as a handful of transnational corporations, still concentrate around half of the available land and in many cases, worse still, keep it unproductive.

A requiem for the free market

Eat what you don’t produce and don’t eat what you produce. This is the secret of the offshoring and financialized export agriculture that has been promoted in the country in recent decades. A fundamental milestone in its implementation was the policy of trade and financial liberalization imposed in the mid-1980s, with the help of the International Monetary Fund, the US State Department and the enthusiastic action of the ineffable Bill Clinton – a self-styled “friend of Haiti” whose friendship, however, nobody here wants to reciprocate.

In the mid-1990s, this policy deepened, with tariffs on rice imports falling from 35 percent to 3 percent under external pressure. In the same year, the US invested 60 billion dollars to subsidize its own rice production. So-called dumping resulted in Haiti’s production falling by over 50% from 130,000 to 60,000 tons. The selling prices of the peasantry, exposed to unfair competition with the hyper-subsidized American farmer, led to the ruin and exodus of thousands and thousands of peasants. A vicious circle of agricultural ruin, unemployment, hunger, foreign food aid, impossibility of competing with the “free” food sent to the country, and again more ruin, unemployment, hunger, etc., was generated.

“Unfair competition with the hyper-subsidized American farmer, led to the ruin and exodus of thousands and thousands of peasants.”

As a result, Haiti went from being practically self-sufficient in the production of the staple grain of its national diet to importing it massively. Although the case of rice is the most dramatic, it is far from the only one. The nation went from importing less than 20 percent of its food in the early 1980s to importing more than 55 percent from abroad today, mainly from the United States and the Dominican Republic.

This cycle resulted in the partial destruction of traditional peasant agriculture. Some may call it “subsistence,” but for the local peasant it was instead an agriculture of “abundance,” if we consider how trade liberalization has generalized the phenomenon of hunger today. On the other hand, the relationship between food assistance and hunger is direct, as was the case with the “Tikè Manje” program and others developed by USAID, through voucher systems that only allow the population to have access to North American products.

Agritrans S.A.: the flagship

In this scorched earth scenario, after the devastating earthquake of January 2010, the project of transnational, deterritorialized and financialized agriculture began to take shape. Transnational, due to the dominant influence of external capital, beyond the resounding publicity of certain local “entrepreneurs.” It is deterritorialized because the local space becomes a kind of non-place for the capitals that mold the territory in their image and likeness: bananas from Haiti or Guadeloupe, soya from Brazil or Paraguay, sugar cane from the Caribbean or European beet sugar, etc., are all the same. And it is financialized because what this agriculture tends to produce is not food, but foreign currency. In short, it is an agriculture that satisfies only the hunger for capital accumulation.

A cautious detour with a good local guide allowed us to enter the lands of Agritrans S.A., the company of de facto president Jovenel Moïse, which became famous for its involvement in one of the largest embezzlements of public funds in the country’s history, amounting to a quarter of the national GDP. This was confirmed by Senate investigations – before its closure in January 2020 – and by the Supreme Audit Court, before its reduction, by presidential decree, to nothing more than a mere consultative body.

The inhabitants of the Limonade and Terrier-Rouge area, in the North-East Department, are in awe of all things related to this fabled expanse of land. And for those who feel neither fear nor respect, there are armed guards to remind them. They told us to stop and threatened to shoot as soon as the motorbike we were traveling on around their perimeter on National Route 6 slowed down. Unable to film or photograph the accesses, we had to clandestinely enter the estate through some twisted wire fences on the side of a canal. Surprisingly, a barren plain then spread out before us. Whether because of the environmental damage resulting from intensive production without crop rotation, or perhaps because the tenure of these lands today serves more the assertion of local power than the process of real accumulation, we saw not even a trace of a cultivated field. Today, Agritrans S.A. is a huge, uncultivated estate, surrounded by crowds of peasants who cannot even get access to a “handkerchief of land”, as the locals eloquently put it.

“Agritrans S.A. became famous for its involvement in one of the largest embezzlements of public funds in the country’s history, amounting to a quarter of the national GDP.”

The “Nourribio” project was set up here in 2013, on the land of the man who would later become the country’s president. The 1,000 hectares in front of us were donated for a project that envisaged the intensive production of bananas, mainly for export to Western countries. It also took the form of a free zone, exempt from taxes and other charges. The land for its establishment was expropriated from 3,000 peasants and granted in concession for a renewable term of 25 years. The aforementioned promises of employment fell far short of expectations: only 200 people were being employed, according to information from 2014. And the people who lost land? The small amount of their compensation was spent on the basic necessities of everyday life. With no land to work or produce, their “beneficiaries” soon found themselves unemployed, expelled to the capital, expelled abroad, or reduced to starvation, if not a combination of all of the above.

According to the specialist Georges Eddy Lucien, in the face of the banana production crisis in the French overseas departments (Guadeloupe and Martinique), “the Northeast – of Haiti – appears in the eyes of investors and international institutions as an ideal alternative territory, where production costs (labor, available land) are much lower…”. The impoverishment of Haitian workers has meant that the wages of an agricultural worker can be 25 times lower – 25 times! Not to mention if we compare it with the average wages of a Frenchman or a North American.

History is a boomerang. The first shipment of Agritrans bananas arrived at the port of Antwerp in Belgium in 2015. The same port that flourished during the slave trade and during the reign of Leopold II. A century ago, thousands of kilos of ivory and rubber, the product of slave exploitation in the Belgian Congo, arrived there. Today, it is bananas from Haiti, produced by one of the most impoverished workforces on the planet.

Operation dispossession

However, at least the construction of Agritrans S.A. involved mechanisms that we will call quasi-legal – although not moral – through the expropriation and compensation of peasant properties, measures taken perhaps because of the international visibility of the project.

But the policy of land grabbing has deepened in recent years, according to the leaders of the main peasant organizations during a recent colloquium on the subject held in the central region. There, for example, the national government ceded by decree no less than 8,600 hectares of fertile land to the Apaid family, one of the richest in the country. Another agricultural free trade zone is supposed to be built there, but this time for the production and export of stevia for the multinational Coca-Cola

But back to the Northeast. After long walks along impassable rural roads, flooded by rain, mud and state neglect, we were able to visit several communities that have suffered and are today facing the dispossession of their lands by local landowners, foreign companies and armed gangs.

In Terrier Rouge, Irené Cinic Antoine of the “Small planters” movement told us that she has owned a large plot of 6,000 hectares of land since 1986. In 1995, under the progressive government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the process to legalize their tenure began. Since then, the common lands have been divided between agriculture, charcoal trees and livestock. Their ownership rights were even published in the official state newspaper, but the documents were later disappeared by anonymous hands.

We also talk to Christiane Fonrose and her husband, as they stoke the fire on the mountain of earth inside which burns the wood that will be turned into charcoal. It is one of the few remaining means of survival in the region, although its ecological costs are well known to all, particularly to the peasantry. From his unshakeable faith, Fonrose tells us: “The land is God’s thing, which God created for us. Before creating his children, God created the earth. (…) But then they took the earth out of our hands. Today we have nowhere to plant, nowhere to graze some small animals, the children cannot go to school (…) We are in a very difficult situation”.

“The common lands have been divided between agriculture, charcoal trees and livestock.”

We were also able to visit peasant organizations in Grand Basin who are currently resisting the permanent hostility of invisible actors who are trying to take over land that was ceded to them by the state, again during the Aristide era. After another long trek along the difficult rural roads, our interview had to be conducted in the pouring rain, as even the roofs and doors of the small house on the plot were stolen. Here, on the edge of mineral-rich mountains, 1,500 organized peasants have been able to work 148 kawo of land (about 200 hectares) to produce sugar cane, maize, manioc and even honey and kleren – a peasant sugar cane brandy – in a sovereign and agro-ecological way.

A little over a year ago, a heavily armed group broke in, disrupting their crops, stealing or killing their animals, destroying fences, buildings and their meager agricultural implements. Evidently these were neither neighbors nor amateurs, as the operation involved the deployment of expensive bulldozers. Even today, the land that was taken remains unproductive, and the peasants are constantly threatened not to try to recover it. So far, no state body has given them any response. “Without the land, outside the land, we peasants are worthless. We voted for them ourselves, but it seems that they don’t need us anymore,” concludes Antoine.

Today there are barely 350 people left, including only a handful of young people: most of them have been forced to migrate to the capital Port-au-Prince or even abroad. In the long siege they have been suffering since then. The National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INARA) has hardly dared to take sides with them. Coincidentally, according to recent reports, the Moïse government is seeking to eliminate this body in the new constitution it is now preparing. According to Wilson Messidor, leader of MOPAG, the project to dispossess them of their land would be closely linked to the mining resources in the area, and to the construction of the so-called villages, semi-closed residential neighborhoods that USAID is building for the workers in the free trade zones.

USAID appears, in fact, as the de facto civil authority in these territories, and its projects are constantly growing and multiplying, as indicated by the numerous signs on the roadsides. According to an anonymous Cuban engineer, the US mega-cooperation organization operates through loans and projects, indebting the state and the communities, in order to guarantee control of strategic areas for their water and mineral resources.

It matters little, following Eduardo Galeano’s metaphor, whether the monarch is King Banana, Queen Stevia or King Manufacture. Haiti continues to be determined by the blessings of nature and the curses of those who dominate history. We will continue, in the next note, to unravel the mysteries of this “poor rich country” which, in the international division of labor, has been subjected to the task of exporting poverty and importing humanitarian aid. We will talk about the export processing zones and the bizarre project to turn Haiti into the “Taiwan of America.”

Lautaro Rivara is a sociologist, researcher and poet. As a trained journalist, he participated as an activist in different spaces of communications work, covering tasks of editing, writing, radio broadcasts, and photography. During his two years in the Jean-Jacques Dessalines Brigade in Haiti he was responsible for communications and carried out political education with Haitian people’s movements in this area. He writes regularly in people’s media projects of Argentina and the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean including Nodal, ALAI, Telesur, Resumen Latinoamericano, Pressenza, la RedH, Notas, Haití Liberte, Alcarajo, and more.

This article previously appeared in Peoples Dispatch.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com