Illustration by Billie Carter Rankin. Photographs by Tasos Katopodis and Chip Somodevilla, via Getty Images.

From Gaza to Sudan to the streets of America, the oppressors of our time demand mass resistance. Not just protest, but an organized, unrelenting struggle. Black radical politics remind us that only collective power can dismantle the machinery of genocide, ecocide, and state violence.

Originally published in Hammer and Hope.

Now is the time of monsters. From ongoing genocide in Gaza and Sudan, the foreign-backed forever war in Congo, and Western occupation and recolonization of Haiti to capitalist greed and state violence against immigrants, unhoused folks, and racialized people in the context of the fires ravaging the Los Angeles area, it’s difficult to feel optimistic about the state of politics in 2025. This feeling of dread can be only partially attributed to the Trump regime, given that these catastrophes started, intensified, or ossified under Joseph R. Biden. As the U.S. government continues to make a mockery of democracy and justice by, for example, putting a bounty on the head of the democratically elected president of Venezuela while threatening sanctions on the International Criminal Court for issuing righteous arrest warrants for Israeli war criminals, it can seem naïve to believe that if we organize and fight, we will indeed win. But this is precisely what must guide Black politics in 2025: steadfast belief that the truth is on the side of the oppressed, unshakable faith in peoples’ power, and abiding hope that the masses can organize and unify. As mutual-aid collectives, migrant cleanup brigades, student organizers, anti-imperialist organizations, worker uprisings, and tenants’ unions have demonstrated, even if we are resource poor, we are people rich — and this means we have the raw material for victory.

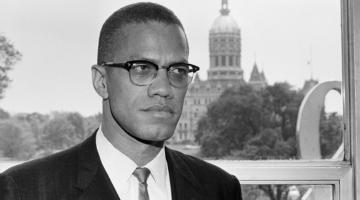

There are manifold examples in Black politics of this dialectic between radicalism and repression. In 1951, radical Black organizers charged the United States with genocide. Many were subsequently jailed, prohibited from international travel, and blacklisted. This defiant act, codified in the “We Charge Genocide” petition, was rooted in a practice of mutual comradeship — radical African descendants’ ethical, epistemological, and political practice of collaboration, reciprocal care, and learning in community that was in turn rooted in radical work, organizing, and movement building on behalf of the racialized, colonized, and oppressed. It is a form of relation aimed at protecting and preserving not only movements and organizations but also one another. It entails the lateral and intergenerational practice of legacy maintenance — including archiving, commemoration, public remembrance, and truth-telling — predicated upon the enduring commitment to, advocacy for, and protection of those who, because of their radical praxis, are intentionally erased from popular memory, obscured, and/or silenced. Every aspect of charging genocide, from the conceptualization, drafting, and editing of the petition to its circulation, publicizing, and filing before the United Nations, was collaborative and required a community of comrades. Likewise, the complainants and their supporters raised national and international consciousness about genocidal aggression against Black people and its relationship to world peace, and cultivated international solidarity while navigating attacks from the Subversive Activities Control Board and the U.S. State Department alongside criticism from politicians and scholars who reduced “We Charge Genocide” to subversion.

We are five years beyond the uprisings in response to the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in the summer of 2020. That world historical moment buoyed the spirits of activists, organizers, and freedom fighters; politicized people in real time; sharpened and cultivated resources of dissent and solidarity; and renewed revolutionary optimism about the possibility of a world beyond policing, anti-Black racial oppression, and ruling class domination. Since then, we have experienced vehement “whitelash,” right-wing reaction, and efforts to build a “cop nation,” while our political methods, organizations, ideas, curricula, rights and liberties, and very bodies are under intense assault. This vicious drive was intensified after Hamas launched Operation Al-Aqsa Flood on Oct. 7, 2023, and the subsequent upheaval that engulfed the world, not least on U.S. college and university campuses. With violence and repression reminiscent of, and in some cases exceeding, that meted out against racial justice protesters in 2020, power brokers — police officers, university administrators, elected officials at all levels of government, those with the power to hire and fire — sought to crush anyone and everyone who stood up for Palestinian self-determination and by extension, liberation for all oppressed, exploited, and marginalized peoples.

Given this reality, radical Black politics in 2025, vivified by mutual comradeship, must charge the United States, its Western partners, and its opportunistic vassal states with its manifold atrocities. We charge genocide for the destruction of life worlds from Gaza and Sudan to the domestic colonies of the United States. We charge ecocide for climate catastrophe, spurred by capitalist plunder and white supremacist inhumanity, that inequitably impacts oppressed people who contribute the least to ecological devastation. We charge scholasticide for the destruction of universities in Gaza, the militarization of our campuses, and attacks on veracious curricula at all levels of education. We charge epistemicide for the destruction of ways of knowing that guide stewardship of the land, respect manifold ways of being, and uphold People(s)-Centered Human Rights. We charge femicide for the ongoing attack on women’s bodily sovereignty, unchecked violence against racialized and colonized women and girls, and the devalorization of oppressed genders to uphold the patriarchal objectives of capitalist racism and Wall Street imperialism.

Importantly, this radical Black politic, this practice of mutual comradeship, must be rooted in organizing aimed at revolutionary transformation — the painstaking work of cultivating and sustaining unity, discipline, and coordinated action. More and more people are being immiserated, reduced to bare life, and subjected to premature death. The historical task of those of us committed to a world beyond capitalist racism is to make evident the overriding choice of our time: socialism or barbarism — that is, political and economic democracy or social and material sufferation. Of course, this is no easy task. Antagonism and alienation, distraction and despair, individualism and indolence pervade our social relations. Nonetheless, trying together is our only option.

The Alliance of Sahel States, pan-African and socialist parties, anti-imperialist formations, mutual-aid and abortion networks, bail funds, abolitionist organizations, migrant brigades, student intifadas, and progressive unions, to name a few, are already modeling aspects of radical fightback and mutual comradeship. But we need more. As we enter an epoch of advancing fascistic revanchism, people in Black politics must out-organize, be more united, and have more class solidarity than the elites who are quite literally invested in our demise. Mass struggle can and must be the basis for disempowering and expropriating the hoarders of the good life. Unified and organized Black working-class and poor people in particular can be a seismic force against the current vision of the world that is crushing the majority.

Charisse Burden-Stelly is an associate professor of African American studies at Wayne State University. She is the author of Black Scare/Red Scare: Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States and the co-editor of Organize, Fight, Win: Black Communist Women’s Political Writing. She is a member of the Black Alliance for Peace and Community Movement Builders.