To commemorate Black August, read Safiya Bukhari's essay on political prisoners and political movements. Her words resonate today.

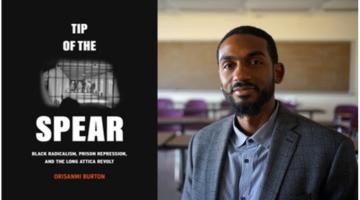

To mark Black August, we reprint “On the Question of Political Prisoners” by Safiya Bukhari (1950 - August 24, 2003). Born in the Bronx, Bukhari came to political consciousness during college, joining the Black Panther Party and, later, the Republic of New Africa. Targeted by the FBI’s notorious COINTELPRO, Bukhari went underground but was captured, charged with weapons violations, and convicted and sentenced to forty years in prison during a sham trial. Bukhari spent almost a decade incarcerated. She was refused medical care by the prison authorities and segregated from other prisoners as she was deemed a “most dangerous” inmate.

Upon her release, Bukhari dedicated herself to advocating and organizing support for incarcerated Black Panthers and the hundreds of other political prisoners and prisoners of war locked up in state and federal penitentiaries in the US. She helped form the Free Mumia Abu-Jamal Coalition and the Jericho Movement. Abu-Jamal called Bukhari a "Lioness for Liberation.”

Bukhari’s “On the Question of Political Prisoners,”originally appeared in the magazine Crossroad: A New Afrikan Captured Combatant Newsletter, published by Chicago’s Spear and Shield Publications. It is a concise and pointed analysis not only on political prisoners, but on political organizing, especially at a time when, as she puts in “the movement is totally fragmented and in a state of disarray.” To begin the long process of rebuilding the movement Bukhari reminds us of some fundamental principles: posturing is not politics, jockeying for a position is not a position, consciousness raising takes time and patience, and the conditions inside a prison are an indictment of the society beyond the prison walls.

Bukhari writes: “Revolution is not about gaining name or organizational recognition at the expense of building a foundation for a movement that will lead us to victory. In order to create the conditions for revolution we must go back to basics and deal with the fact that revolution is protracted, it doesn’t happen overnight therefore we have the time to make sure we lay the correct foundation and build a strong movement based on work.” As we face down a long night ahead, Safiya’s Bukhari’s resonate today. We reprint her “On the Question of Political Prisoners” below.

On the Question of Political Prisoners

Safiya Bukhari

There is no question that support for political prisoners and prisoners of war should and must be an integral part of any movement for liberation. There is no question, that is, for people who have dedicated their lives to the struggle for freedom in this country and realize that it is not possible to talk about a movement for liberation if you fail to liberate people who are incarcerated as a result of that struggle for liberation.

What is called into question, therefore, is whether or not we are serious about revolution and liberation.

I remember sitting in the back room of the Harlem office of the Black Panther Party on Seventh Avenue and listening at political education class while Mao Tse Tung’s Red Book was being discussed. This particular day the passage under discussion was Tell no lies and claim no easy victories. I interpreted that to mean, go to the people, organize the people, work among the people and tell no lies about what we want and what we’ve done and what we have accomplished. We have to build a strong bond of trust with the people and show them by example that we’re different from the politicians and corporate businessmen and others that say anything and do anything to get the people to go along with their program.

This lesson, Tell no lies and claim no easy victories, has been the cornerstone of my understanding of what this struggle is supposed to be about. If we take the Tell no lies approach to organizing, then we take the time out to build a foundation for a movement that is destined to bring us the victory we say we’re fighting for. There would be no need to organize separate programs to educate the community to the existence of political prisoners because as we work to organize rent strikes and take control of abandoned buildings to create decent housing in our community through our sweat equity. We would be talking while we’re working about how Abdul Majid and others organized tenant associations in the East New York and Brownsville sections of Brooklyn such as the Oceanhill Brownsville Tenants Association. While we’re organizing around the issue of quality education that teaches our true history and role in this society we could talk about Herman Bell and Albert ‘Nuh’ Washington and their work with the liberation schools. While we’re organizing food co-ops and other survival programs we can talk about Geronino Pratt, Sundiata Acoli, Robert ‘Seth’ Hayes and all other political prisoners and prisoners of war who worked in the Free Health Clinics, the daycare centers and went to prison as a result of their active participation in organizing efforts around issues that directly affected the Black and oppressed communities.

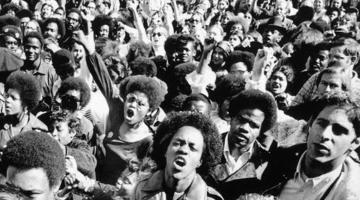

Because our ‘movement’, for lack of a better word, has deteriorated to the point that the majority of our organizing is done through demonstrations, rallies, conferences and press conferences; the only way we feel we can talk about the issue of political prisoners is when we drag them out for show and tell time or when we need to legitimize what we’re doing. This raises the question, “Are we serious about struggle? Or are we just profiling?” If we’re not serious then we need to let our political prisoners off the hook and tell them to “Do what you think is best for you!” If we are serious then we need to stop ego tripping, stop profiling, stop rabble rousing and get down to the serious work or organizing. Talk is cheap, action is supreme!

Political prisoners didn’t become political prisoners out of a vacuum. They went to prison, for the most part, as members of political formations. There are over 150 political prisoners in jail across this country. The majority of these brothers and sisters are serving upward of 25 years to life and at least one, Mumia Abu Jamal, is facing death. At the time the majority of these people went to prison there was a thriving movement on the street. They are sitting there now and the movement is totally fragmented and in a state of disarray. They are being pulled in a lot of directions by fragmented organizations that are more interested in posturing as the ‘vanguard’ and jockeying for position than doing the work of organizing the people. I constantly wonder why it is necessary for them to be fighting among themselves to be the titular ‘vanguard’ of a ‘movement’ when there are millions of people that have to be organized? If they all got down today to the talk of organizing New York City, or any of the other communities across the United States, there would still be room for more help. We wouldn’t even step on each other’s toes and would be glad to share the work because that’s how much work that has to be done. That is, if we were serious about the job of organizing for liberation.

The term ‘political prisoner’ means nothing to the average brother or sister on the block because the terms ‘liberation’ and ‘revolution’ mean nothing. The words have no meaning for our people, no real meaning, because we have done no real organizing, and educating for liberation. This lack of consciousness among our people, and the lack of support for political prisoners is a direct result of our lack of concrete work among our people. The days of people getting involved in struggle for great socialist ideas is long gone, if they ever existed. Our people require examples of what concrete changes will occur in their condition if we collectively fight for change. Once they are shown the example of what could be achieved, they are more likely to support struggle. When they are confronted by how the state – government – police respond to people who dare to speak out and organize and educate against a system that has consistently exploited, brutalized and oppressed them, they are more likely to support political prisoners.

Some of us mistake the people’s anger at, frustration with and distrust of the system as meaning they are ready for revolution. It is true that they possess a deep seated anger at the system, that they distrust the system, but it’s also true that they have not made the connection between the source of this anger and distrust and creating a revolution.Our people are more inclined to participate in a race riot than a revolution. They would support a drug dealer before they’d support a revolutionary. Why? For a number of reasons, chief being that the drug dealer is in the community constantly, is known by the community and has picked up on a lesson that the revolutionary used to know. The drug dealer understands that he has to give something back to the community. He employs the local people and therefore, even if it’s pennies, makes a difference in the life of the community.

This is not an indictment of our people, but rather an indictment of the deterioration of the movement and our complete loss of direction. At some point we should have been able to stop and take an assessment of the state of the movement, especially following the major offensives against the revolution brought on by the government; i.e. COINTELPRO and the destruction of the Black Panther Party. We seem to have forgotten everything we ever learned about revolution, that it’s about the people, making qualitative and quantitative changes in the conditions of our people. Revolution is not about gaining name or organizational recognition at the expense of building a foundation for a movement that will lead us to victory. In order to create the conditions for revolution we must go back to basics and deal with the fact that revolution is protracted, it doesn’t happen overnight therefore we have the time to make sure we lay the correct foundation and build a strong movement based on work. This is the only real way we can build the necessary support to free our political prisoners and prisoners of war.

A final word, to our political prisoners, we used to know that prison was a microcosm of society. That is, we recognized the truism that the conditions of the people that came through the doors of the prison reflected the state of the society without. If you think back to what was happening on the streets at the time you were incarcerated and the activities that were going on among the prisoners in the institutions and compare that to what the people who are coming into the institutions are talking about and doing now, you can deduce for yourself the state of the movement today. Just as we have a job to do out here, you have a job to do in there. Being in prison does not release you of your obligations to educate to liberate some of you seem to have forgotten that. What being in prison does is change the venue from which you organize–change the playing field.

I remember another class that took place in the Harlem office of the Black Panther Party. This lesson had to do with the 10-10-10 Program. This was a lesson on organizing. We had to learn the 10-Point Program and Platform of the Party. We had to learn the 26 rules of the Party. We had to learn the 8 points of Attention and the 3 Main Rules of Discipline. We had to learn the motto and internalize all of it. We had to learn it for the day when we would be on our own without other Panthers so that we could carry out the tasks of the revolution. Once we internalized these teachings we were ready to go out and organize. The theory was that if each one of us organized ten people, and those people organized 10 people–, and those people organized ten people–the third group, if each one of them organized 10 people, would number 10,0000 people. It’s a time consuming method of organizing, but it’s tried and true. This was the approach to organizing that I used in my section when I was in the Party. During the time I was incarcerated in Goochland, Virginia the people that were in my section in the community were the ones who stood by me and sent me packages and cards and were there waiting when I was released from prison in 1986.

Organizations come and go, but we have to create within our people the spirit of struggle. We have to build a movement to liberate our people. The issue of political prisoners is part of that movement we are building and in building that movement we must understand that this is not a separate issue. It is an integral part of that movement, it can’t be put in front of the movement and can’t be an afterthought. It must be woven into the very fibers.

Safiya Bukhari, “On the Question of Political Prisoners,” Crossroad 5 no. 4 (January-March, 1995), 6-8.