A voting booth sits at a polling station in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in April 2020. (Thomas Werner / Bloomberg)

The city’s abstainers could determine who wins Wisconsin, a critical swing state, this November.

Originally published in The Nation.

It’s two devils,” a resident of Parkview Apartments in Milwaukee’s northwest side told me. “And I know a lot of people who feel the same way.” It was a hot July afternoon, a few days before the Republican National Convention, and canvassers from the group Power to the Polls were out hoping to mobilize Black voters for the coming presidential election. The arduous work of engaging potential voters door-to-door “in rain, sleet, or snow,” as one canvasser put it, began in October, when President Joe Biden and Donald Trump were the obvious front-runners. But even with Biden stepping down from the race Sunday and endorsing Vice President Kamala Harris, who could potentially become America’s first Black and Asian woman president, the group has a rough road ahead as November looms closer.

In recent years, both Democrats and Republicans have been vying for the attention of Wisconsin’s Black residents, who are largely concentrated in Milwaukee, the most populous city in this critical swing state. The Democratic Party chose the city as its convention host in 2020, with Republicans following suit this year. Today, Harris is expected to be in Milwaukee for what could now be her first official campaign stop as she vies for the presidency, with Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes up for grabs. But the frenzy of outreach from party leaders to lure voters who have been disenfranchised for generations is like trying to sweep water out of the Titanic.

Amid deindustrialization and especially after the 2008 financial meltdown, Black Milwaukeeans have been drowning in an economic crisis unlike almost anywhere else in the country. Study after study has shown that the city has ranked among the bottom on almost every economic and social metric—from employment to education to median income—for Black residents. Wisconsin as a whole hasn’t fared much better. It’s been a fact that was largely ignored until it became less politically expedient to do so.

Until recently, party leaders had been so focused on wooing coveted white swing voters—some of whom voted for Obama and then flipped to Trump in 2016—that they lost sight of a quieter group who are often younger, more left-leaning, and more diverse. I call them slide voters: They aren’t swinging between Republicans and Democrats; they’re dropping out of politics altogether.

Since May, I’ve surveyed dozens of Milwaukee residents about how they plan to vote in November, and whether they would vote at all. More than a third hadn’t voted in the last two presidential elections. Some are open to voting this year but weren’t sold on either Biden or Trump. Many may never come around—even with a new nominee.

Wade, 33, was born in Milwaukee and raised in the city’s south side. He periodically works for his uncle as a roofer to make ends meet. “Who can I really vote for?” he asked. “I want there to be a better world. I want it to be like how I was growing up.” Wade reminisced about a childhood he said was free of the kind of violence—both from police and among residents—that he’s seen plaguing the city since his mid-20s.

Wade is also finding steady employment difficult—he’s been registered with a temporary staffing agency, but the work has been inconsistent. “I’ve been trying to get a job for damn near two years now,” he said. “I can’t win for losing.”

The Biden-Harris administration has been touting record low unemployment rates for Black Americans as part of its campaign messaging, a statistic that should resonate for Milwaukeeans. But according to Marc Levine, a researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, unemployment statistics are a flawed measure. Those rates don’t include a key group: people who have been out of the workforce for so long that they’re not counted in federal employment data.

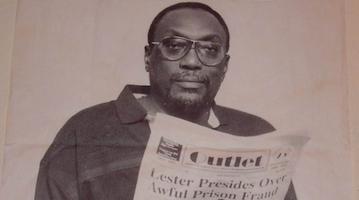

“The unemployment rate only calculates people who are in the labor force and looking for work,” Levine told The Nation. “If somebody is out of the labor force, they’re not working, and they’re just discouraged. They’re not showing up at the unemployment office every day to register and find a job. For African American males with such a long period of chronic joblessness, and with the great difficulty of finding employment in Milwaukee, over time this group has simply fallen out of the labor force.”

Even when jobs are secured, adequate wages aren’t guaranteed: Of the country’s 50 major metropolitan areas, Milwaukee has the lowest Black median income. The modest gains in employment under the Biden-Harris administration can’t counter the weight of an economy that has crushed Black workers in the city since the 1970s and ’80s, when heavy manufacturing began abandoning Milwaukee and other industrial centers.

At the same time, the neoliberal, market-driven policies advanced by both Republicans and Democrats only exacerbated the precipitous economic decline of the state’s Black communities. The Opportunity Zones Donald Trump heralded during his presidency? The former president depicted the tax break program for rich investors as a boon for Black America. Levine calls them a “tax scam.” From defunding public housing to promoting corporate subsidies, the policies put into place by both parties have empowered multinational companies to drain public coffers and shut off the faucets.

Levine has been studying racial and economic inequality in the state since the 1990s, and he’s only seen local elected officials treat it like the crisis it is in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd protests. Even then, there were more lofty promises than actual outcomes. No amount of rhetoric can formidably challenge the tide of economic depression that has made Milwaukee an “archetype” of “racial apartheid and inequality,” as Levine put it in an exhaustive 2020 report.

To siphon off Black voters disenchanted with the status quo, Republicans have started to resort to the kind of half-baked, hypocritical cultural appeals for which they have long derided Democrats. The Republican Party of Milwaukee County’s field office sits across the street from a beauty supply store and on the same block as two Black barbershops in the city’s historically Black Bronzeville neighborhood, and it displays posters geared toward Blacks and Latinos.

In a June fireside chat aimed at Black Milwaukeeans (but consisting mostly of white attendees), US Senator Ron Johnson hopped on the criminal justice reform train, referencing the “unfairness” of Trump’s felony case, after having campaigned as a law-and-order candidate in the 2022 midterms. “My guess is that in the Black community, there’s all kinds of situations where you believe the prosecutors using discretion had not been fair,” Johnson told the audience. After lambasting “identity politics” and “wokeness” in recent election cycles, Republicans like him have clumsily tried to wield both in their latest play for Black voters.

Trump’s personality may well win over some Black Milwaukeeans who feel they have run out of options—perhaps more than ever in recent history, given that Black support of the Democratic Party is at a historic low. But the Grand Old Party’s policies will likely prevent Black voters from ever flipping to Republicans en masse.

Jonathan Jarmon, executive director of Power to the Polls Federal Fund, a political action committee, believes that educating Black Milwaukeeans about the threat of a second Trump administration—as outlined, for example, in the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 document—will be the best way to improve turnout. “People are worried about a complete Republican takeover,” Jarmon said, with Trump and the Republican Party “doing more things to strip away rights for everyday people to benefit the wealthiest people in this country.”

Ahead of his arrival in Milwaukee for the RNC, Trump reportedly called the city “horrible”—neglecting to mention that his own party, which controls Wisconsin’s state legislature, has made it inhospitable for many of its residents. With Republican policies in place—from blocking minimum-wage increases to union busting to voter-suppression laws that keep business-friendly Republicans in power—Wisconsin has frequently been called the worst state for Black Americans.

Cedonia, 38, makes her living doing gig work, delivering for DoorDash and styling hair. When she was growing up, her mom drove a school bus, but her dad got sick at a young age and wasn’t steadily employed. “Living in Milwaukee, it’s rough,” she told me. The last time she voted was for Barack Obama. When Trump and Biden faced off in 2020, she couldn’t muster a vote for either of them. “I didn’t like them. I felt like they were racist. I felt like certain stuff they was doing wasn’t going to change anything.” For her, the Black community needs a lot of changes. “There’s not enough housing. I don’t think there’s enough shelters for the homeless.”

She doesn’t plan to vote this year either. Reflecting on the Biden-Harris administration, she expresses concern about its defense spending overseas. “They want to go to war with these other countries, they’re giving them a whole lot of money. What are you doing for people in the US?” As Vice President Harris attempts to align herself with Biden’s domestic successes, she will also have to accept his foreign policy failures, including the virtual blank check he wrote to Israel in a relentless bombardment of Gaza that has killed thousands of Palestinians.

Cedonia and Wade are among the alarming number of Black Milwaukeeans who have become “slide voters.” Their effect on presidential elections isn’t in moving the needle toward one or the other party but in lowering turnout.

In 2016, Wisconsin saw the lowest Black voter turnout for a presidential election in the state’s recorded history, nosediving from 79 percent in 2012 to 47 percent, per census data. As unprecedented as that drop had been, Black voter turnout in 2020 was even lower: Only 44 percent of the Black Wisconsin electorate showed up at the polls. For all the rhetoric about Black voters’ saving democracy, many seem to feel there isn’t much to save. When wages are meager, rents are unsustainable, and affordable homeownership is practically impossible, “democracy” feels more like an abstract concept than a meaningful rallying call.

Presidential campaigns often emphasize “bread and butter” policies that are meant to appeal to the working class in coveted Midwest states. But working-class Black Milwaukeeans could use some brick and mortar. The heavy industry that once proliferated in the city has crumbled, just like the potholed roads running through Black neighborhoods.

In an election year, Biden was sure to erect signs at some of the city’s many road construction sites crediting his success. “Project Funded By President Joe Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,” the signs read. But energizing an eroded Black electorate that has been left to suffer through decades of abandonment will continue to be a work in progress. Celebrating a historical first in the form of Kamala Harris may work for some Black voters, but it might not be enough for a crucial number of Milwaukee residents who feel that their priorities always come last.

Malaika Jabali is the author of It’s Not You, It’s Capitalism, from Algonquin Books.