Marielle Franco’s Assassination: One of Tens of Thousands of Black Murders in Brazil

“Brazil`s terrocratic regime continues producing black dead bodies in astonishing scales without disturbing the normalcy of everyday political life in this country.”

Every year, at least 60,000 individuals are killed in Brazil, at least 160 murders every day. The majority of the dead are black, young and from urban peripheries where the state is present only through its delinquent police force. Although the police are not responsible for all these deaths, it directly or indirectly pulls the trigger that kills black youth. Books, academic articles, brief-reports, film documentaries, op-eds all have ad nausea denounced this genocidal proportions of violence in the country known as “the land of cordial man.” It is a waste of time, energy and resources. Nobody cares or they care too little to turn these deaths into a national scandal. There is an underlying belief that the word genocide is an overstatement to depict what is going on in a country where racial boundaries are supposedly not rigid as in the United States or South Africa. Apartheid and the Jim Crow are usually mentioned to compare Brazil´s 'benign' race relations in opposition to these countries’ racial violence. The fact is that, consistent with its ugly history, Brazil maintains a regime of racial terror that does not differ from these two nations’ past and present system of racial domination.

We are talking here about a perverse social structure dependent on black suffering, the fallacies of racial harmony notwithstanding. In Brazil, the say goes, “everybody has black and indigenous blood. The poor in their veins, the rich in their hands.” This is a fair picture to a country which was the last nation in the Western hemisphere to abolish slavery, and where until now domestic servants are treated as slaves (with a dark little room in the backyard of the house of white families), let alone the lynching spectacles that are increasingly common. It is hard to find a parallel between current homicidal violence against blacks here with other nations in the so-called democratic world. Imagine a place where in peacetime 160 black individuals are murdered every day? Imagine a country where twelve civilians are ‘legally’ killed by the police on a daily basis? Black bodies lying in the streets or favelas alleys are not newsworthy.

“Imagine a country where twelve civilians are ‘legally’ killed by the police on a daily basis.”

From slavery to racial democracy, Brazil never stopped been a black graveyard. Be it through the ordinary violence of poverty and malnutrition or through the homicidal and police violence so rampant in its racially divided cities, the cruelty of the Brazilian society resists time. Although not unique, the work of police embodies such national anti-blackness. Police terror hit new records every year. According to the Brazilian Forum of Public Safety, in 2016 the police killed 4, 224 civilians. It was 25% more than the killings registered for 2015 and just part of the 21,000 murders by the police between 2009 and 2016. The profile of the victims: 99% are men, 82% are youth between fifteen and twenty-nine-year-old, and 76% are black. In 2017 the rogue military police of Rio de Janeiro -- a state with one of the most organized campaigns against black genocide -- also hit a new record: alone it murdered 1120, somewhat less than Sao Paulo (965 deaths) and much more than the number of civilians killed in the United States in the same period. These statistics consider only “legal killings” and obviously do not count the “disappeared” and “unknown” that have turned poor and predominantly black urban communities in Brazil into macabre geographies.

Rio and Sao Paulo are just a small picture of rotten police that commit unspeakable acts of violence throughout Brazil. There are no reasons to believe the numbers will not increase in the next year and years ahead with the military occupation of urban peripheries by the Brazilian Army. Until now, the Army has been deployed by the coup coalition (that governs the country since the controversial impeachment of Dilma Rousseff) to “pacify” Rio de Janeiro, but “Rio is a test case” for Brazil as a whole.

Ironically, the Army intervention in Rio may provide an ‘opportunity’ for white progressive forces to reconnect with the destitute poor for whom the state of exception is the norm. As white middle-class activists see in the presidential decree authorizing the Army to take charge of Rio de Janeiro’s public security a new phase in the coup against democracy, for black activists “the favelas have been under occupation since always,” “the coup has long been deployed against the favelado.” As we oppose the Army invasion, we also remind ourselves that daily checkpoints, arbitrary arrests, collective warrants, shots from helicopters, killings and disappearances show that there is no state of rights for those living in the permanent shadow of death. What is the favela if not a foreign land and its inhabitants the enemies to vanish?

“Chronically Unfeasible”

Perhaps the best way to describe Brazil is that it is chronically unfeasible (at least from the perspective of blacks), to borrow the forceful title of Sergio Bianchi’s 2000 film documentary. One would think that waves of modernization the country passed through in the last decades would at least disturb its colonial structure. I suspect things will not get any better but rather far worse. Despite the regime of citizenship, decolonization is still to be completed. My pessimism does not leave me blind to the vibrant political life of a tireless black movement that has fought and succeeded in challenging the myth of racial democracy and in granting some rights through some affirmative action policies implemented by the Workers Party. Because of black struggle, some concessions have been made. Black activists usually joke that “if we don’t fight they revoke abolition.” The struggle has been vital to sustaining some space to breathe. Yet, the ongoing black genocide recommends us to be pessimists. Malcolm X’s unapologetic question rings true to Brazil: “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there's no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that's not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven't even pulled the knife out much less heal the wound. They won't even admit the knife is there.” Here, the police-state makes sure the knife is in place, daily reinforcing a racial, social order in which blacks are exploited in low-paid jobs, segregated in the favelas, killed and disappeared.

If Brazil is, again from the perspective of blacks, a chronically unfeasible place, what we do then? As we fight to keep ourselves alive and to make black lives livable, we also know that lobbying with progressive left-wing forces in the political system, mobilizing civil society with protests in the streets, starving ourselves in hunger strikes, drafting manifestos, writing books and op-eds like this very one you read now are not enough. The fact is that we are tired of burying our people…the old, the young, the heathy, the sick. Despite the tireless activist labor of an old and new generation of black individuals, Brazil`s terrocratic regime continues producing black dead bodies in astonishing scales without disturbing the normalcy of everyday political life in this country.

Ordinary Anti-Black Wars

On March 14, Marielle Franco, a 38-year old activist in the Brazilian black movement, was murdered, having been shot five times at Rio`s downtown when coming back from a public event about black women’s exclusion from the political system. Marielle was a black lesbian and favelada city councilwoman fearlessly vocal against police terror. Days before her killing she denounced on twitter the disappearance of two youth kidnapped by the police in the neighboring favela of Acari. She was also leading the human rights commission to monitor police and military abuse during the military intervention decreed by president Michel Temer.

Marielle and her driver Anderson Gomes’ political assassinations mobilized thousands of social activists in Brazil and around the world. The United Nations released a statement saying “she was one of the leading voices in defense of human rights in the city…developing a political platform related to the fight against racism and gender inequalities and the elimination of violence, especially in the poorest communities of Rio de Janeiro.” Black activist Marcelle Decothé wrote in her social media: “the killing of our Mari is a message to all black bodies that fight for rights in the favela. The message was for us. The pain is unbearable because they cruelly silenced the voice of one of us.”

“The killing of our Mari is a message to all black bodies that fight for rights in the favela.”

In the aftermaths of Marielle`s murder, she would be killed again and again by right-wing activists on social media, police officers and conservative judges spreading fake news about her supposed involvement with drug-trafficking and “bandits” in the favela. The fake news is aimed at justifying police terror against Marielle, Anderson and the people of the favelas, who are, in the racist imagination, naturally-born delinquents, and those denouncing police abuse are “advocates of thugs.” By savaging the biography of Marielle, as it is usually done with ordinary black Brazilians killed by the police, they tried to ‘re-kill’ her and to demoralize the struggle of the black movement and particularly of black women seen as the source of urban insecurity.

Marielle dared to transgress the spatial/racial order of Brazilian society. She was one of the few black women occupying elected positions in a country in which they/we are virtually absent from the spheres of political and economic power, despite the fact that blacks make up half of the population. According to Revista Forum, black women are underrepresented in the Brazilian national Parliament where they are 11 out of 513 congresspersons in the lower house and only 1 out of 81 in the Senate. This reflects their structural position in the larger society as well. Data from the Brazilian government itself and UN Women indicate that black women are 61% of domestic workers, they earn 58% of a white woman’s income, they are 68% of the female prison population, and while white woman’s homicide rate decreased 9% from 2003 to 2013, the victimization of black women increased 54%. Finally, black women are .04% of the CEOs in Brazil’s larger companies.

“Franco was the only self-declared black person serving in the Rio`s council.”

The same structure is replicated in Rio de Janeiro, an apartheid urbanity internationally sold as Brazil`s marvelous city. Marielle was elected to the city council with the painful and unfunded work of black women from Rio`s sprawling favelas where she also lived with her child. Facing the structural barriers of a corrupt political system controlled by white men and facing the too-slow awakening of the leftist parties to the gendered racial question of representation, she managed to be the fifth most voted councilperson in Rio`s 2016 election. She was one of the thirty-two black women serving office in city councils throughout Brazil and the only self-declared black person serving in the Rio`s council.

All this makes her death a devastating event for millions of black Brazilians who still hold some hope in representative democracy. And yet, the tragedy about her death is that it was not a tragedy at all. Her life was an exception, her death was expected. Isn`t the exploited, beaten, pained, dead body of black favelada women part of Rio´s and Brazil`s political landscape? Anyone familiar enough to this hellish country knows the mundane rituals of degradations of black lives that at times may spike some momentary scandal but that at the end of the day is just “terror-as-usual.” How many more deaths will we grieve before the machine of state terror can be stopped? Who can protect us from the police? At this very moment, a young black Brazilian is being devoured by the ordinary violence enacted or facilitated by Brazilian state and sanctioned by civil society's deadly mode of racial relations.

“Her life was an exception, her death was expected.”

Dangerously walking in the fine line between been pessimistic and cynical, I want to restate my sense of hopeless in Brazil, for this anti-black ordinary war is part of the national character and its ethos. To be fair, the execution of Marielle created an ephemeral moment of political solidarity with thousands occupying the streets of Rio to denounce police terror. There is also a definite mobilization among a young generation of a middle class and non-black youth that wants a diverse and inclusive Brazil. The question is: how long can such solidarity can be sustained, and is progressive civil society willing to side with black youth when tanks, arms, grenades and hit the favela. That seems to be the concern evoked by Lourenco da Silva, a friend of Marielle. He was straightforward: "The message was to the favela, not to the White leftist and macho [movement] of Rio. The idea was to tell the favelado, be careful, watch out; there is no space for you here, don’t protest, don’t denounce. Accept!” Political solidarity is precarious, contingent and most of the time ineffective because the favela is another country and the favelado is a foreign enemy.

We are pessimists of the intelligence but also optimists of the will. Thus, we struggle. During Marielle’s and Anderson`s funeral, grieving and despaired black activists reaffirmed their commitment to a radical struggle to redefine democracy and to redefine the terms of black participation in the nation. The message was that we will not be silent, they will have to kill us all, we are all Marielle. At least for a moment, a black death disrupted the hegemonic narratives of violence in Brazil and broke the wall of indifference in the traditional public sphere. Until when? If the Military Police is not banished, if the relation between the favela and the country is not redefined, and if the war against black people is not ended, it seems to me that it is Kafka’s remarks that fit tragically and painfully well here: there is hope, but not for us!

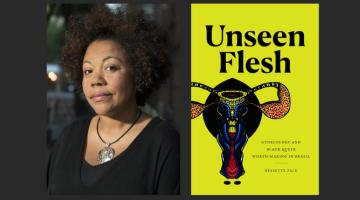

Jaime A. Alves is a black Brazilian journalist and anthropologist. He is the author of The Anti-Black City: Police Terror and Black Urban Life in Brazil (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press)