Police Kill. We March. Why?

We must instead think creatively about how to either take total community control of law enforcement as an institution or to bring about an independent, nation-building, self-governing reality.

“We are able to develop new approaches to community security adapted to the current material conditions of our community.”

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt was a very worried man. A. Philip Randolph made him that way with a threat to mobilize 100,000 Negroes (as they were then called) to march on Washington for jobs and justice. Just the thought of it was terrifying to the white mind because they weren’t just Negroes. They were radical Negroes. Randolph’s rhetoric proved it. He had this to say about World War II:

“…[Q]uestions are being raised by Negroes in church, labor union and fraternal society; in poolroom, barbershop, schoolroom, hospital, hairdressing parlor; on college campus, railroad and bus. One can hear such questions asked as these: What have Negroes to fight for? What’s the difference between Hitler and that ‘cracker’ [Governor Eugene] Talmadge of Georgia? Why has a man got to be Jim Crowed to die for democracy? If you haven’t got democracy yourself, how can you carry it to somebody else?”

The prospect of thousands of militant questioning Negroes descending on the nation’s capital became a high priority concern for the White House, and no comfort was taken from Randolph’s comments about the movement:

“The March on Washington Movement is essentially a movement of the people. It is all Negro and pro-Negro, but not for that reason anti-white or anti-Semitic, or anti-Catholic, or anti-foreign, or anti-labor. Its major weapon is the non-violent demonstration of Negro mass power.”

“If you haven’t got democracy yourself, how can you carry it to somebody else?”

The very idea of mass action by America’s African population was so novel and intimidating in its mystery that Roosevelt made concessions in the form of Executive Order 8802. It prohibited racial discrimination in the defense industry. This had been a movement demand, and because it was met, the threatened march did not occur.

As we know, needed civil rights objectives were not fully achieved in 1941, and in 1963 the movement saw fit to revive the march on Washington idea. Remarkably, there was no less fear of thousands of Black people in one place notwithstanding the passage of more than two decades. Civil Rights Movement historian Taylor Branch explained:

“Dominant expectations ran from paternal apprehension to dread. On Meet the Press, television reporters grilled Roy Wilkins and Martin Luther King about widespread foreboding that ‘it would be impossible to bring more than 100,000 militant Negroes into Washington without incidents and possibly rioting.’ In a preview article, Life magazine declared that the capital was suffering ‘its worst case of invasion jitters since the First Battle of Bull Run.’ President Kennedy’s advance man, Jerry Bruno, positioned himself to cut the power to the public address system if rally speeches proved incendiary. The Pentagon readied nineteen thousand troops in the suburbs; the city banned all sales of alcoholic beverages; hospitals made room for casualties by postponing elective surgery.”

“President Kennedy’s advance man positioned himself to cut the power to the public address system if rally speeches proved incendiary.”

The March on Washington came and went, and White America was able to calm its own fears about mass rallies – particularly when only a few years later non-violent demonstrations stood in stark contrast to militant urban insurrections that erupted in cities across the country. Suddenly, when they considered the alternative, the white establishment leaders urged non-violent protest.

America’s Africans also reached certain conclusions. The popular Black analysis connected racial reforms with marching, and for the balance of the 1960s, and well into the 21st Century, the popular response to any extreme act of racism was: “We’ve got to march!” It was a call that was music to the ears of the political establishment and the police forces that served it. That’s because marches, no matter how noisy or emotionally charged could be contained and were controllable because organizers had to seek permits in advance as well as coordinate march routes with police. The establishment was also pleased that organizers often scheduled demonstrations for Saturdays. That ensured the system would be neither inconvenienced nor disrupted because government and corporate operations were down for the weekend.

It took a while, but eventually Black people realized that this is no longer A. Philip Randolph’s America. Simply mobilizing masses of African humanity – even when they are a million strong – will not worry the powers that be, much less move them to concede power.This awakening was first demonstrated in Ferguson, where demonstrators who might normally have followed the usual script, began to act out in new and different ways, catching the establishment by surprise and leading them to panic and frantically search for the non-existent “leaders” who might contain the unrest. The demonstrations triggered by the George Floyd murder were even more exasperating because they were unpredictable, coordinated through social media, global in their dimension, and they included an informed militant component that aimed aggression at real estate that was in some way representative of the police state.

“This is no longer A. Philip Randolph’s America.”

The establishment became desperate to control the George Floyd demonstrations, and its first inclination was to attempt to coopt the movement. The phrase “Black Lives Matter” became a part of every corporate brand. Amazon, Apple, Walmart, Disney and others tossed large grants to the movement in an attempt to trap it in the web built by the non-profit industrial complex. Those controlling popular culture officially accepted the protests as part of Americana. Establishment propagandists launched a sustained, subtle campaign to direct the tone and tactics of the movement by distinguishing “protesters” from “rioters” with the latter condemned to a status lower than the killer cops who are responsible for the demonstrations in the first place.

Though the George Floyd demonstrations diminished in their frequency and intensity, they never ended completely. What had become smoldering embers of protests were stirred and then fanned into wild flames of rage by events in Kenosha, Wisconsin. But as committed demonstrators soldier on, wearing out their shoes walking city streets night after night, there is the inevitable question: “What are we really trying to accomplish by doing this?” If the immediate objective has been to get the world to sit up and take notice, then check that box. Mission accomplished. If the more fundamental objective is to end police terrorism, there is obviously much more work that must be done, and after decades of marching and burning down cities, we are left to conclude that these tactics alone are insufficient.

“Those controlling popular culture officially accepted the protests as part of Americana.”

At its core, a movement’s effectiveness is determined by the extent to which it destabilizes or at the very least inconveniences those with power. Street protests retain that potential if they are creatively designed products of analysis of the vulnerabilities of the system. Hitting the establishment’s weak spots hard can produce reforms. But there will never be reforms that threaten those features of the system that are vital to maintaining a capitalist status quo. By now it should be clear that capitalism requires the violent control of African populations, and no amount of marching, burning and looting will change that. Africans globally will see a new, revolutionary reality – even with respect to police - when they finally become powerful players on the world stage by wresting the natural resources of Africa from the greedy clutches of imperialism and using them for the benefit of Africa’s people everywhere. But that might take generations. What then to do in the short-term about the ever-growing mountain of black bodies pierced by cops’ bullets?

Professional athletes may be on to something. Their decisions to sit out games as a gesture of solidarity with the movement against police terrorism suggests a strategy that can hit the establishment where it lives. While corporate sponsors will be unaffected by the postponement of a few games, a long-term players’ boycott could place billions of dollars of sports revenue in jeopardy. The potential lies not only with professional athletes. The many thousands of people around the world who have taken to the streets to protest police violence can be more effective if they coordinate and mobilize targeted global boycotts and strikes. Multinational corporations have long thumbed their noses at consumers and workers because they have known there are always other markets and labor forces in other countries to be exploited. However, people coordinated and united globally in their disengagement from the establishment’s economic paradigm can leave capitalism with no alternatives.

Disengagement from the forces of oppression has a long, impressive history. Yeshua (Jesus) and his followers disengaged from Roman imperialism. Maroon communities of enslaved Africans disengaged from the institution of slavery. African runaways from plantations who joined with indigenous people to become the Seminole nation disengaged from (and fought) the United States of America. In more modern times, the Nation of Islam, New Afrikan independence organizations and others have had similar objectives. The strategies of these groups may have varied but what they have all shared is a conscious pride that, in spite of an awareness that they could not defeat their enemies militarily, drove them to preserve their dignity by refusing to beg for mercy, reforms or charitable concessions. They chose not to simply disengage from enemies, but to also build a new, independent, self-determining reality.

“The many thousands of people around the world who have taken to the streets to protest police violence can be more effective if they coordinate and mobilize targeted global boycotts and strikes.”

We will remain true to that tradition if, as we coordinate global strikes and boycotts, we do not approach oppressive forces with a presumption that those with power control our fate, and that our activism is merely to urge more civilized behavior by cops. We must instead think creatively about how to either take total community control of law enforcement as an institution or to bring about an independent, nation-building, self-governing reality that completely eliminates police officers from our daily existence.

Africans have a long history, both in Africa and the Diaspora, of administering systems of social control in our communities without alien squads of uniformed, armed people with badges engaging in harassment, intimidation and murder. For example, the warriors of traditional Africa kept order. Councils of elders ensured justice. In Cuba there have been Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. The Panthers organized community patrols. The Nation of Islam organized and trained the Fruit of Islam. At the Million Man March, the simple mass commitment to preserving the peace ensured no incidents of conflict or violence, and no one displayed weapons to make that happen. We are no less able to develop new approaches to community security adapted to the current material conditions of our community.

If we must march, let us not do so blindly, aimlessly and with hopes for sympathy. Let us march instead toward disengagement from an oppressive empire and with a resolve to establish a new, self-determined independence.

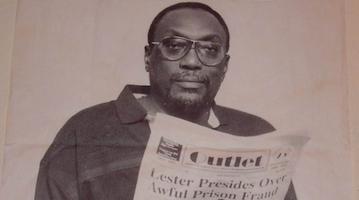

Mark P. Fancher is an attorney and long-time contributor to Black Agenda Report. He can be contacted at mfancher[at]comcast.net.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com