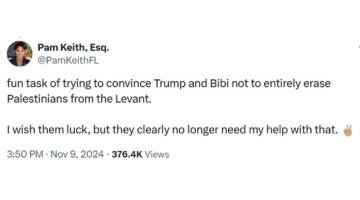

Carnegie Mellon's "expressive activity" policy forbids groups of more than 25 people from protesting on campus. This group of students, faculty, and alumni holding signs labeled "1" through "29" technically violates that policy. Jonathan Aldrich

Dozens of campuses quietly implemented new “expressive activity” policies over the summer—effectively banning many forms of protest.

Originally published in Mother Jones.

Last school year’s historic protests over the war in Gaza roiled campuses and dominated headlines, with more than 3,100 students arrested nationwide. Over the summer, the protests cooled off and students returned home. But college administrators spent the summer crafting new free speech policies designed to discourage students from continuing what they started last spring. Between May and September, over 30 colleges and university systems—representing nearly one hundred campuses—tightened the rules governing protest on their property.

The protest encampments that appeared on more than 130 campuses last spring served as a visual reminder of the 2 million displaced people in Gaza. Students held teach-ins, slept in tents, created art together, ate, and prayed in these makeshift societies—some for hours or days, others for entire weeks or months. The free speech organization FIRE estimated last week that 1 in 10 students has personally participated in a protest regarding Israel’s war in Gaza. The protesters demanded that their schools disclose any investments in (variously) the Israeli military, the state of Israel, or the military-industrial complex in general—and disentangle their endowments from war-makers.

Some student groups won meetings with administrators, disclosure of the terms of their college’s endowment, or representation for Palestine studies in their school’s curriculum. A few schools agreed to work towards divestment or implement new investment screening procedures. Students elsewhere, though, saw no concessions on their goals from college administrators—and were left, instead, to spend months doing court-ordered community service or working through a lengthy school-ordered disciplinary process.

Prior to last year’s protests, “time, space, and manner” restrictions on campus protest were considered standard practice, said Risa Lieberwitz, a Cornell University professor of labor and employment law who serves as general counsel for the American Association of University Professors. Many universities had pre-existing policies prohibiting, for example, obstructing a walkway or occupying an administrative office. Those policies were usually enforced via threats of suspension or expulsion. This year’s restrictions are different, said Lieberwitz, who previously described the new rules as “a resurgence of repression on campuses that we haven’t seen since the late 1960s.”

Lieberwitz is particularly concerned with policies requiring protest organizers to register their protest, under their own names, with the university they are protesting. “There’s a real contradiction between registering to protest and being able to actually go out and protest just operationally,” she said. “Then there’s also the issue of the chilling effect that comes from that, which comes from knowing that this is a mechanism that allows for surveillance.” Students who are required to register themselves as protest organizers may prefer to avoid expressing themselves at all.

“The point of having a rally is to be disruptive, anyway,” said MIT PhD student Richard Solomon, who participated in last year’s campus protests. For Solomon, divestment is personal. Last month, Mohammed Masbah, a Gazan student he refers to as his brother and who spent several months living with his family, was killed in an Israeli airstrike. As Solomon pointed out in a column for the student newspaper, Masbah was likely killed with the help of technology developed at American universities like MIT.

“MIT has lots of rules about ethical funding, about the duty to do no harm with one’s research,” he told Mother Jones. “And yet they refuse to apply any of those rules to their own behavior, their own research, their own institutional collaborations.” It’s hard, he said, for students to respect protest rules when their school doesn’t respect its own rules, either. (When asked to comment, a MIT representative pointed me to a speech by the school’s president last spring, in which she stated that MIT “relies on rigorous processes to ensure all funded research complies with MIT policies and US law.”)

Beyond demanding that protests be registered, many schools have banned camping on their grounds. Some have required that anyone wearing a mask on campus—whether for health reasons or otherwise—be ready to present identification when asked. Others have banned all unregistered student “expressive activity” (a euphemistic phrase that generally covers a range of public demonstrations including protests, rallies, flyering, or picketing) gatherings over a certain size. Still others have banned all use of speakers or amplified sound during the school week (including, in one case, the use of some acoustic instruments).

At Carnegie Mellon University, students and faculty were informed during the last week of August that any “expressive activity” involving more than 25 students must be registered—under the organizers’ names—at least three business days prior to the event, and be signed off on by a “Chief Risk Officer.”

In response, a group of Carnegie Mellon students, faculty members, and alumni lined up on a grassy campus quadrangle holding up signs labeled “1” through “29.” This act, now prohibited on Carnegie Mellon’s campus, drove home the policy’s absurdity—on a campus of 13,000 students, half of whom live on campus, a gathering of 25+ people may be harder to avoid than to initiate.

David Widder, who earned his PhD at Carnegie Mellon last year, called the new policy “authoritarian,” and unlike anything he’d seen during his six years at the institution. “We hoped to playfully but visibly violate the policy—and show that the sky does not fall when students and faculty speak out about issues that matter to them,” he told Mother Jones. “We can’t credibly claim to be a university with these gross restrictions on free expression.”

According to a statement by the university’s provost, the new policy was intended to “ensure coordination with the university and support the conditions for civil and safe exchange.”

Linguistics Professor Uju Anya, who spoke at the rally, pointed out that at least $2.8 billion of Carnegie Mellon’s research funding has come from the Department of Defense since 2008. “We know that our universities have skin in the game now, in the weapons and in the money,” Anya said. “So, ultimately, Carnegie Mellon is in bed with baby bombers, and they don’t want us—the members of this community, who also have a stake in what the university does—to openly question them.”

At some schools, the conflict over newly instituted protest policies has already made its way to the courts. The ACLU of Indiana announced August 29 that it would be suing Indiana University over an “expressive activity” policy which, like CMU’s, was implemented in late summer. The policy under debate defines “expressive activity” in part as “Communicating by any lawful verbal, written, audio visual, or electronic means,” as well as “Protesting” and “Distributing literature” and “circulating petitions.”

The policy limits “expressive activity” to the hours between 6 a.m. and 11 p.m. “This is written so broadly, if any one of us was to wear a T-shirt supporting a cause at 11:15 p.m. while walking through IU, we would be violating the policy,” Ken Falk, legal director of the ACLU of Indiana, said. “The protections of the First Amendment do not end at 11:00 p.m., only to begin again at 6 a.m.” Since Indiana University is a public school, it is bound by the First Amendment and can’t limit speech as strictly as a private college.

Lieberwitz, the AAUP lawyer, said she expects more legal challenges like the ACLU’s this coming year. According to the Crowd Counting Consortium at Harvard University, protests on college campuses are spiking again, though not at the levels seen last year. On at least two campuses, protesters have already been arrested. And between August 15 and September 3, there wasn’t a single day without some sort of Palestine solidarity action on a college campus somewhere in the United States.

The following is an incomplete list of US university protest policies changed between May and September of 2024.

Carnegie Mellon University: As of August 23, an “event involving expressive activity” occurring on campus “must be registered with the University if more than 25 participants are expected to attend” at least three business days in advance.

University of California (1o campuses): Camping or erecting tents is forbidden as of August 19. Masking “to conceal identity” is banned.

California State University (23 campuses): “Camping, overnight demonstrations, or overnight loitering” is banned, as are “disguises or concealment of identity,” as of August 19.

University of Connecticut (five campuses): As of August 21, students cannot make amplified sound through speakers or megaphones, or use certain acoustic instruments like “trumpets, trombones, or violins” in public spaces at any point during the day Monday through Friday, with official university events excepted.

University of Denver: On May 9th, protests were restricted to specific on-campus locations.

Drexel University: On September 9th, a new set of “activism guidelines” were released, reiterating a previous ban on encampments, banning demonstrations in buildings, and prohibiting protests after 10 p.m.

Emerson College: As of August 23, protests may only occur between 8 a.m. and 7 p.m., and must be pre-registered with the college.

Emory University: As of August 27, camping is prohibited on campus, and protests are prohibited between midnight and 7 a.m.

Franklin and Marshall College: As of August 28, “Individuals may not wear a head/face covering or other device that is intended to conceal the identity of the wearer.” Items such as “illuminated signs” and non-battery-operated candles are now prohibited. Protests are restricted to two hours in length, and must be registered five days in advance.

Hamilton College: As of August 20, demonstrations and protests must be registered with the school. “No person may erect a structure, symbolic or otherwise, associated with a demonstration or protest without obtaining permission during the registration of the event.”

Harvard University: Plans to ban “outdoor chalking” and “unapproved signage” are in process as of July 30, according to a draft obtained by the Harvard Crimson. Indoor protests have already been banned as of January 2024.

Gonzaga University: As of August 23, overnight demonstrations are prohibited.

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign: As of August 21, camping is prohibited except in designated areas.

Indiana University (nine campuses): As of July 29, “expressive activity” is limited to the hours between 6 a.m. and 11 p.m., and any “signs or temporary structures” are now required to be approved at least 10 days in advance of “expressive activity” by the university.

James Madison University: As of August, no “tents or other items” may be used to create a shelter on campus unless approved by the university. Chalking on walkways is prohibited. “Camping” is defined as “the use of any item to create a shelter.”

University of Maryland (11 campuses): on August 19th, interim public space use policies were implemented prohibiting unauthorized encampments and unauthorized use of amplified sound.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology: As of August 30, unauthorized tent encampments are prohibited. Authorized demonstrations on campus may only be organized by “Departments, Labs, or Centers, recognized student organizations, and employee unions.”

University of Massachusetts, Boston: As of August 30, organizers are required to notify the university of demonstrations five days in advance. Indoor protests are prohibited. Tents are prohibited at protests. Demonstrators may not wear “attire that attempts to disguises or conceal the identity of the wearer that the institution may be deem [sic] as obstructing the enforcement of these rules or the law.”

University of Minnesota (five campuses): On August 27, university administrators unveiled new “guidelines for spontaneous expressive activity,” which state that all protests must end by 10 p.m., must use no more than one megaphone, and that groups of over 100 people must register their spontaneous expressive activity at least two weeks in advance.

Northwestern University: A new demonstration policy effective September 5th bans overnight protest, sets up designated zones for chalking and flyering, and requires students to remove face coverings when asked by a “University official performing their duties.”

University of Pennsylvania: As of June 7, encampments are banned, as are any overnight demonstrations, and “non-news” livestreaming. “Unauthorized overnight activities” are to be considered trespassing.

Pomona College: As of August 2024, encampments are prohibited, and noncompliance may result in “detention and arrest by law enforcement.” Additional police officers have been hired to patrol campus.

Rice University: New policies in effect August 30 define a demonstration as expressive activity by “one or more persons,” limit hours and locations for demonstrations, and note that “The University may immediately terminate any unauthorized event, including an unapproved Demonstration.”

Rutgers University: As of August 20, demonstrations must be held between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. and only in “designated public forum areas.”

University of South Florida system (three campuses): As of August 26, “activities in public spaces” after 5 p.m. are prohibited unless students request a reservation.

SUNY Buffalo State University: On August 22, draft policies were made public limiting posters on bulletin boards, restricting “Public assemblies (e.g., protests, picketing)” in public areas, and reiterating a prohibition on the establishment of or maintenance of “temporary or permanent living spaces” on university property.

SUNY-Fredonia: As of August 21, “assemblies lasting more than four hours” are prohibited, as are encampments.

Syracuse University: As of August, “unauthorized use or assembly of tents or other temporary shelter structures” is prohibited.

University of Texas at Austin: as of July, University free speech policies were updated to clarify police involvement. “The University of Texas at Austin Police Department (UTPD) and any other peace officer with lawful jurisdiction may immediately enforce these rules if a violation of these rules constitutes a breach of the peace, compromises public safety, or violates the law.”

Virginia Commonwealth University: As of August 9, anyone on University property covering their face must show identification. Encampments are explicitly prohibited, “unless approved in advance by the University.”

University of Virginia: Updated “Rules on Demonstrations and Access to Shared Spaces” as of August 26. Non-permitted tents are now forbidden, no tent can stay up for over 18 hours, unless “in use for official University or school events,” and anyone wearing a mask on University property must present identification if asked. No outdoor events are permitted between 2 a.m. and 6 a.m.

Virginia Polytechnic Institute: As of August 30, camping on university property is banned, as is overnight use of university property for events, with the exception of property “that has been wholly or partially designated as a sleeping area such as a residence hall.”

University of Wisconsin, Madison: Updated its policy on “expressive activity” August 28. “Expressive activity,” defined as activities protected by the First Amendment including “speech, lawful assembly, protesting, distributing literature and chalking,” is now prohibited within 25 feet of university building entrances.

Did your school implement a new protest policy this year? Email shurwitz@motherjones.com.

Correction, September 13: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s protest policy as prohibiting protests within 25 feet of university buildings, rather than prohibiting protest within 25 feet of university building entrances.

Sophie Hurwitz is a Ben Bagdikian editorial fellow covering politics and social movements at Mother Jones. Previously, Sophie covered education and the criminal-legal system for the St. Louis American, and worked as a fact-checker for New York magazine. Reach out to shurwitz@motherjones.com or @sophiehurwitz on Twitter.