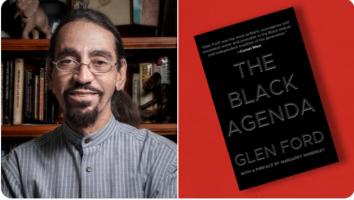

The compilation of Glen Ford's work, "The Black Agenda" was published by OR Books posthumously. In the introduction he recounted his life story and career.

By way of an introduction to this anthology of my writings on politics and race, it seems appropriate to set out a brief account of my life. I’ll keep it short; just sufficient to give a bit of context to the pieces that follow. I hope, at some point in the future, to write a full autobiography.

I was born Glen Rutherford in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1949. I was a “red diaper baby.” My mother Shirley was a consummate political organizer and, in 1958, my father Rudy became the first Black man to host a non-gospel television program in the Deep South. By the age of eleven I was reading newswire copy on my father’s radio show in Columbus, Georgia. My professional career began in 1970 at James Brown’s radio station in Augusta, Georgia, WRDW-AM, where the “Godfather of Soul” shortened my surname to “Ford.” Determined to put radio at the service of the people, WRDW helped empower grassroots activists to challenge the local white power structure, culminating in a Black rebellion that left six dead but pulled the city out of the political backwaters.

After a stint as a reporter at the Communist Party USA’s Daily World newspaper in New York City, and a close collaboration with the Jersey City chapter of the Black Panther Party—which was then in full retreat from a nationwide police and FBI “final offensive”—I returned to the airwaves in Columbus as a newsman at WOKS-AM radio. There, I tried to replicate the organizing strategy we had deployed in Augusta the previous year, filling the station’s hourly newscasts with sound clips from local grassroots activists. Key among them was the newly-organized local chapter of the Chicago-based African American Patrolmen’s League, comprised largely of Vietnam veterans whose top priority was fighting police brutality. The Black cops became the point-persons of the local movement when they publicly removed the American flag patches from their uniforms to protest the department’s racist intransigence.

Regional and national human rights and labor leaders journeyed to Columbus in solidarity. By summer, the city was under curfew and burning, with multiple arsons nightly for more than two months—fires rumored to have been set by on-duty Black police officers with accelerants provided by Black soldiers at Fort Benning, the neighboring Army base. Columbus was wrenched into a new era by the nation’s longest sustained urban rebellion on record.

My next stop was WEBB-AM, Baltimore, another of James Brown’s radio stations where, in addition to local reporting, I created my first radio syndication. Black World Report, aired on Sunday afternoons, was a half-hour weekly program of national and global news from a Black liberationist perspective. It was a poor man’s syndication—the roster of stations broadcasting the program was limited by the availability of used recording tape from WEBB’s studios—but the project provided me with experience in national, long-form program production.

In June of 1972 I got my first union job with a living wage at WOL-AM, Washington, D.C.’s top-rated, Black-oriented station. I brought along Black World Report and immersed myself in the city’s local and national Black political networks. I worked most closely with the African Liberation Support Committee, in solidarity with guerilla movements fighting colonialism and white minority rule on the continent, and with tenants’ organizations that, even in the early ’70s, were struggling against creeping gentrification of Black neighborhoods. I organized my own speaking circuit under the theme “Merging the Masses, the Media and the Movement,” sustained mainly by relatively small honorariums from Black student unions.

It was the Golden Age of Black radio news, a profession that was called into existence by, first, the explosion in the number of Black-oriented radio stations in the ’60s and, second, Black people’s demand that these stations provide information relevant to their lives and struggles. Black radio news was birthed by the “movement.” Two Black radio news networks were founded in the early ’70s. After almost three years at WOL-AM, I was hired by the Mutual Black Network (with eighty-eight affiliated stations), headquartered in downtown D.C., where I soon became Washington Bureau chief, effectively shaping the network’s hourly broadcast content. I brought much the same approach to national reporting as I had employed in local news, methodically reworking the list of Black “leaders” that the network’s news gatherers would call for reaction to world and national events. Movement activists and other leftists were put on the A-list.

At this time, I reluctantly discontinued production of Black World Report, the little syndication I had created in Baltimore three years earlier. I became a founding member of the Washington Association of Black Journalists in my first year at the Mutual Black Network. The WABJ was soon dominated by Blacks from the general corporate media who felt no obligation to the Black political movement that had gotten them jobs. Rather, these corporate climbers saw themselves as performing a “role model” service to Black America simply by holding down prestigious positions. I quit the WABJ shortly before it became part of the newly-formed National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ), which quickly devolved into a kind of guild that counts Black faces in corporate newsrooms but fights for nothing worthwhile to the masses.

On top of my bureau chief duties, during my four years at the network (1973–77) I also served, variously, as Capitol Hill, State Department, and White House correspondent and delivered a daily political commentary, plus three or four hourly newscasts per shift. But a gaping “hole” in the national Black broadcast journalism array cried out to be filled; there was no African American counterpart to the Sunday morning news interview programs Face the Nation (CBS), Issues and Answers (ABC), and Meet the Press (NBC). The three network television institutions generated the newsmaker quotes that made the headlines on Monday morning and shaped much of the national political conversation for the rest of the week. Black America needed its own newsmaking mechanism.

I spent the next three years developing America’s Black Forum (ABF), which finally debuted with about thirty affiliated stations on January 16, 1977, the same week as Roots. ABF was the first nationally syndicated Black news interview program on commercial television, produced at ABC affiliate WJLA-TV. The program made Black broadcast history. Over the next four years, ABF generated national and international headlines nearly every week. Never before—and never since—had a Black news entity commanded the weekly attention of the news services (AP, UPI, Reuters, Agence France-Presse, and even Tass—the Soviet news agency) and the broadcast networks. ABF consistently beat ABC’s Issues and Answers in the ratings at the network’s own Washington affiliate.

Although a considerable journalistic success, America’s Black Forum began its broadcast life without a sponsor. As the bills piled up, my co-producer Peter Gamble and I searched desperately for an advertiser to fill the commercial slots, or an investor to ward off creditors. To keep ABF on the air, we felt compelled to sell a majority interest in the program to a Black investors group in return for assumption and payment of the debt. The program earned its first advertising dollars four months after its debut and was soon operating in the black, allowing ABF to pay off its creditors—no thanks to the crooked investors, who never paid a cent of the debt. Peter and I continued to produce ABF for the next four years, fighting with the crooks all the while, but knowing that a legal showdown would destroy the syndication. In 1981, rather than risk killing the program that had served Black journalism so well, we sold our remaining shares to the crooks for cash and left the syndication. ABF continued on the air for another twenty-five years, but very seldom made news again.

In 1979, while still host, producer, and co-owner of ABF, I set up Black Agenda Reports—the first project I would give that name—which provided five short-form programs each day on Black women, history, business, sports, and entertainment to sixty-six radio stations. The syndication produced more short-form programming than the two existing Black radio networks combined, but folded when the Reagan administration drastically slashed the budget of BAR’s sponsor, Amtrak. I revived the name Black Agenda Report when Margaret Kimberley, Bruce Dixon, and I launched our Black weekly internet political periodical in 2006.

Black radio news was in deep decline by the early ’80s, a casualty of corporate consolidation and asset inflation in which radio station prices skyrocketed under competing bids from big chains. Small, “stand-alone” owners of one or two stations, many of whom took pride in providing local and national news to their communities, were replaced by chain managers who reported to corporate headquarters thousands of miles away. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), a creature of presidential appointments, now defined the “public interest” so narrowly that local and national news became optional—and ever more stations were opting out. Increasingly, there was no one at local stations authorized to put syndicated programming on the air; all such decisions were made at corporate headquarters. Black radio news was decimated as hourly local and/or national newscasts became relics of the past. The same thing was happening in white-oriented radio.

True to their class, the Black political establishment was concerned only that minority entrepreneurs be allowed to participate in the corporatization of media. What I would later call the “Black misleadership class” did nothing to safeguard the informational needs of their constituents. And the grassroots movement that had brought Black radio news into existence to serve a previous generation was now dormant. Amidst this spreading corporate wasteland, I produced the McDonald’s-sponsored radio series Black History Through Music, aired on fifty stations nationwide. (The sponsor bought the airtime). For two years I was national political columnist for Encore American & Worldwide News magazine, founded by the crusading and fearless Black publisher Ida E. Lewis, who was still hanging on in the Age of Reagan. I earned a modest living voicing commercials for radio and television. During this period I also got a kick out of verbally thrashing corporate executives who paid a hefty fee to a Madison Avenue outfit that specialized in preparing executives for encounters with the press. I justified taking on these assignments in the belief that the clients were wasting their money, since corporate journalists would never be as hard on the top brass of big companies as I was. (But if I did do some political harm, I apologize.) The advent of the first generation of low-cost computers allowed me to publish several issues of the print political journal The Black Commentator—a title I would use again twenty years later—and Africana Policies magazine. However, I found that distribution of hard-copy publications was prohibitively expensive, and both projects were short-lived.

As an executive board member of the National Alliance of Third World Journalists (NATWJ), I traveled to Cuba, Nicaragua when the Sandinista government was under siege by U.S.-backed terrorists, and Grenada two months before the U.S. military attacked and occupied the island nation. I authored The Big Lie: An Analysis of U.S. Press Coverage of the Grenada Invasion (IOJ, 1985).

In 1987 I partnered with Patrice Johnson and Anthony Devon to launch Rap It Up, the first nationally syndicated hip-hop music show, broadcast on sixty-five radio stations. During its six years of operations, Rap It Up allowed me to play a key role in the maturation of a new African American musical genre that, in its early years, “sampled” snippets of Malcolm X speeches and for a time revived the Black Power political ethos of the ’60s.

By the early ’90s, however, the corporate recording industry giants were in the process of swallowing up the last of the small, independent labels that had midwifed the genre. “Gangsta rap” was born, not from a racist conspiracy to poison the minds of Black youth, as some believe, but as the result of a corporate label study that found hip-hop’s core audience to be the youngest of any genre in commercial music history: eleven to thirteen-year-olds. As every observer of childhood development knows, “tweens” of both sexes, but especially males, find almost sensuous pleasure in profanity. Misogynist tirades are tween-aged boys’ reflexive way of coping with their own insecurities about how to deal with girls. The recording industry interpreted the study’s results to mean that the tween market would be most profitably served by flooding it with profane, misogynist song lyrics.

Gangsta rap was the undoing of Rap It Up. Although our team was hyper-vigilant in splicing out bad language, affiliate stations feared their broadcast licenses would be in peril if they continued to air the show. Rev. Jesse Jackson denounced gangsta rap and demanded station programmers purge it from their playlists. Rap It Up ceased production in 1993. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 set off a new round of corporate consolidation, but a new medium was emerging that could be useful to purveyors of “information for liberation.” By the year 2000 over half of American households owned a computer and Black internet users were carving out their own cyber spaces. I was working at a Black weekly newspaper that I helped found in northern New Jersey when longtime colleague Peter Gamble phoned to suggest that I consider finding an internet audience for my political commentary. We had not collaborated for almost twenty years, but by conversation’s end plans were begun for a full-blown magazine to be called The Black Commentator—predecessor of the extant Black Agenda Report. Articles from both publications appear in this anthology.