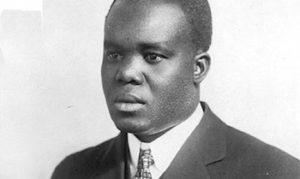

Hubert Henry Harrison was one of the foremost Black socialist and nationalist thinkers of the early 20th century. He was known as "the father of Harlem radicalism." This is the second of of a three-part commentary on works about Harrison.

In his introduction to the first volume, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism (1883-1917), Dr. Jeffrey B. Perry describes Harrison as “the most race conscious of the class radicals and the most class conscious of the race radicals.” Given the over 1,800 pages of text and notes in the volumes under consideration here, it may take some time for students and radical activists to digest Harrison’s contributions, yet the evidence strongly supports the view that Hubert H. Harrison was one of the most influential and most radical of the radicals (in the sense of going to the root) in 20th century America.

Perry’s intriguing description of Harrison’s place in US social history offers historians a window for future inquiries. Even more importantly, Harrison’s life and work offers some urgent lessons for today’s “class” and “race” radicals who wrestle with similar defining features of American society that Harrison challenged a century ago at the beginning of the “American Century”; racial oppression, capitalism, imperialism, opportunism and narrow mindedness in those who would profess to lead the people’s movements. Harrison’s experiences and reflections upon leadership, program, and organization are particularly relevant for those today asking “what is to be done?”

Early Years

Harrison was a working-class immigrant from Saint Croix, a Caribbean Island under Danish control, who arrived in Manhattan in 1900 as a 17-year-old orphan with little more than the clothes on his back and a thirst for knowledge. He arrived the height of what has been referred to as the “nadir” in US race relations, a time during which many of the gains won through the Civil War and Reconstruction were being reversed and “Jim Crow” had been made the law of the land by the US Supreme Court in 1896. Perry contrasts the differing role that race played in St Croix vis a vis the US and notes that Harrison and other emigrants from the Anglo- Caribbean to the US at this time were shocked by the virulence of the racial hatred they encountered.

The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, (1883-1918) captures the energy with which Harrison threw himself into his new world. Eager to learn, indignant and shocked by the virulent white supremacism he encountered in the US, Harrison was in his own words, “irrepressible.”

The young Harrison earned honors at evening high school while working full time in NYC. His brilliance as a student was recognized early on. He continued his self-education by making full use of the public library system and attending the lectures, discussions and debates offered by churches, lyceums and informally organized study groups.

Perry carefully describes and documents the intellectual milieu in which Harrison developed his early views and skills. Harrison was an autodidact, (the “organic intellectual” before Gramsci coined the term) who never ceased to stress the importance of education to his readers and listeners. His 1918 article written for The Voice entitled “Read, Read, Read” expresses the importance he accorded to the cultivation of critical thinking and acquisition of broad knowledge by everyday folks. Harrison’s critical reviews in The Negro World of T. Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color Against White-World Supremacy and The New World of Islam, will be of particular interest given that Stoddard was an early proponent of the “white” erasure theory advocated by white supremacists today.

Harrison led a lively social life in the growing Harlem community and at the age of 26 married Irene Louise “Lin” Horton, a Caribbean immigrant when she became pregnant with their first child.

Harrison studied with a critical eye and identified religious and ideological shibboleths that he found demeaned his race and self-worth as a free-thinking individual. He positioned himself as a Du Bois man following the 1905 Niagara conference that raised criticism of Booker T Washington’s response to the disenfranchisement, racial violence and oppression of Black Americans.

Harrison’s letter to The Sun in 1910 criticized remarks made by Booker T Washington and aroused the ire of the Tuskegee machine which had him summarily fired from the Post Office, a job that had provided him and his growing family with a modicum of economic security. The letter, reprinted in A Hubert Harrison Reader, is an early example of Harrison’s well-crafted prose, critical thinking and wide-ranging awareness of the conditions faced by African Americans in the US:

“Mr Washington says that if black people will cease insisting on the ‘real and great grievances’ and acquire property and manual skill, the grievances, which are the crux of the Negro problem, will decrease and finally disappear. I will make no appeal to the philosophy of history or to anything that may even faintly savor of erudition because Mr Washington and his satellites say that that is bad. But I will appeal to the hard facts.”

Harrison goes on to cite specific examples of how the disenfranchisement of the Negro produced wide disparities in government expenditures on Black vs white schools, protected job discrimination in favor of white over Black workers, and negatively impacted the ability of Blacks to acquire and defend their property. Harrison’s public criticism of Booker T. Washington’s remarks however led to the loss of secure employment, the consequences of which will not be lost on working class readers generally. This act of reprisal from the Tuskegee machine cast Harrison and his family into economic insecurity and thrust him into a life of activism.

The Socialist Party 1911-1914

“The most race conscious of the class radicals”

From 1911-1914 Harrison was the Socialist Party’s leading Black organizer. He sought to enlist the Party to demand the enforcement of the 14 and 15th amendments passed in the wake of the Civil War, but which were not enforced after the end of Reconstruction. The defense of the Black community which he described as “a group that is more essentially proletarian than any other group,” was clearly the duty of Socialists. He hoped that the Socialists would offer a clear alternative to the Republican Party for Black voters, particularly as they migrated to Northern cities.

In 1911 Harrison began by introducing a socio-economic analysis of racial oppression that challenged the Socialist Party’s biological conception of race:

“Politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea. The presence of the Negro puts our democracy to the proof and reveals the falsity of it. Take the Declaration of Independence for instance. That seemed a splendid truth. But the black man merely touched it and it became a splendid lie. And in this matter of the suffrage in the Southern States it is expedient to keep the Negro a serf politically because he is still largely an economic serf. If he should attain to political freedom he would free himself from industrial exploitation and contempt. Of course such a revolution is startling to even think of…” (New York Call, November 28, 1911)

“…the mission of the Socialist Party is to free the working class from exploitation, and since the Negro is the most ruthlessly exploited working class group in America, the duty of the party to champion his cause is as clear as day. This is the crucial test of Socialism’s sincerity…” (International Socialist Review, July 1912)

Harrison’s series of articles for socialist publications prior to World War 1, his support for the International Workers of the World, his criticism of the white labor opportunism of the American Federation of Labor, his book review of William Z. Foster’s 1919 Steel Strike are included in A Hubert Harrison Reader.

The leaders of the Socialist Party rejected Harrison’s call and then went on to endorse the Chinese exclusion acts. Harrison’s writings for the NY Call in 1911, the Socialist Party’s daily paper, included such headings as “The Negro and Socialism: I – The Negro Problem Stated,” “Race Prejudice – II,” “The Duty of the Socialist Party,” “How To Do It – And How Not,” More extensive articles published by the International Socialist Review in 1912 include: “The Black Man’s Burden [I],” “The Black Man’s Burden [II],” and “Socialism and the Negro.” Harrison’s parting letter to the New Review in 1914 “Southern Socialists and the Klu Klux Klan,” was never printed by the journal but was reprinted in The Negro World in 1921. Harrison’s article “Race First versus Class First,” printed in the Negro World in 1920 reminded his audience of the crippling influence of white supremacism in the Socialist Party. All of these articles are reprinted in A Hubert Harrison Reader and Harrison’s struggles with the Socialist Party are recounted and meticulously documented in the first volume of the biography, Hubert Harrison: The Father of Harlem Radicalism (1883-1918).

In hindsight, Harrison’s writings, published by the NY Call and the International Socialist Review, offer one of the earliest, most pointed critiques of white racial opportunism in the US socialist and labor union movements. Harrison’s writings should be required reading for a new generation of socialist minded “class” radicals concerned to place the struggle against white supremacism at the center of their efforts for labor solidarity and fundamental social change. Harrison’s final assessment was that the Socialist Party leadership put the white “race first and class after.”

The most “class conscious of the race radicals”

After leaving the Socialist Party, Harrison focused on organizing in the Black community and pioneered what became a tradition of street oratory in Harlem that continued down through Malcom X. From 1914 to 1917 Harrison drew together a nucleus of like-minded grass roots organizers. His agitation centered on the aspirations and grievances of the African-American community locally and nationally and urged African Americans to organize and advocate for themselves, free from the controlling influence of “white” patrons, an approach he termed “Race First.”

1914- 1918 Race First

“The most class conscious of the race radicals”

Harrison’s frustration with the Socialist Party, led him to pose the question to his fellow Black socialists: “What to do when your “white” friends say no?” Harrison answered that question over the next 15 years through his efforts to unite the Black community around a program of self-defense and self-interest and in organizations free from the controlling influences of would-be friends and allies whose support came with strings attached.

The street oratory that he had pioneered as a leading speaker for Eugene Debs’ 1912 presidential campaign was now focused on Harlem street corners. Harrison soon attracted large crowds with his message of racial pride and demands, radical for the day; that the federal government enforce the 14th and 15th amendments; that black police officers be hired; that Black candidates unbeholden to white power brokers be elected by the Black community; that stores in Harlem hire Black workers; that Black owned businesses be supported and that they in turn support the interests of the community; and that a federal anti-lynching law be passed.

Harrison’s “Race First” approach took organizational form with the Liberty League which was founded in the summer of 1917 as African Americans in East St Louis engaged in armed self-defense against white supremacist mobs and President Wilson was drawing the US into WW 1 to “Make the World Safe for Democracy.”

The Liberty League drew together Black socialists and a much broader section of the Black community in Harlem which had become a center of the Black Diaspora from the US South and the Caribbean. The Liberty League publication, The Voice, edited by Harrison, was the voice of a new movement, rising in tandem with movements nationally and internationally.

At the first meeting of the League, Harrison introduced Marcus Garvey, a newcomer to Harlem from Jamaica. Garvey was a follower of Booker T Washington and had come to the US to raise funds for his Jamaica based Improvement Association.

In 1917 Harrison co-founded the Liberty Congress with Monroe Trotter that met in Washington DC as President Woodrow Wilson was pushing the US into WWI. Military Intelligence and the Justice Department as well as local police began their surveillance and efforts to contain the emergence of these Black led initiatives. Perry has poured through the archives and offers a detailed examination of these early efforts by government agencies who employed both the “carrot” and the “stick” to contain and disrupt the activities of the Liberty League and the Liberty Congress. These state interventions directed against Harrison and Black activists clearly overlapped with similar efforts against the IWW, anti-war socialists, anarchists and supporters of the Russian Revolution.

The ending of chattel bondage and the central role of Black people in the Civil War and Reconstruction was still in living memory in the early 20th century. If the huddled masses of European immigrants and their so called ‘white” labor and socialist leaders were blind to the role that racial disenfranchisement and Jim Crow played in supporting capitalism, the same could not be said for the US ruling elite themselves whose Supreme Court had provided the legal rationale for Jim Crow. Both political parties and much of the leadership of organized labor had, in different ways, overseen, supported or cast a blind eye to the imposition of debt peonage, discrimination and the chain gang on the Black population.

Harrison had attempted to enlist the Socialist Party in the fight to enforce the 14th and 15th Amendments to no avail. He understood that a mass movement was needed and if the white led labor movement was deaf and dumb to the plight of Black America then it fell to the Black community itself, not the “talented tenth,” to lead.

As Wilson pushed the country into a war to “defend democracy” in 1917, Harrison’ wrote “The Descent of Dr. Du Bois,” criticizing an editorial in the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, entitled “Close Ranks,” in which Du Bois advised the African American community to “Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close ranks, shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow-citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.”

On July 4, 1917 Harrison wrote in the Liberty League’s publication, The Voice:

“This nation is now at war to make the world ‘safe for democracy,’ but the Negro’s contention in the court of public opinion is that until this nation is made safe for twelve million of its subjects the Negro, at least, will refuse to believe in the democratic assertions of the country.”

He described the world war as a power struggle between the European colonial powers over the division of Africa and Asia and Wilson’s “Democracy” rhetoric as “dust in the eyes of white workers.”

Harrison aimed to build a movement unencumbered by the need to follow the lead of white politicians or patrons. He had come to value independence not so much as a goal in and of itself but as the basis for true self-determination. “Race First” was Harrison’s pragmatic response to the record of efforts to control and subordinate the struggle against white supremacy and for full equality. It addressed the fundamental need of Black Americans to replace the sense of inferiority and self-loathing induced by white supremacism with self-reliance, political independence, self-defense, cultural affirmations, and self-expression in all fields of human endeavor.

Sean I. Ahern is a retired NYC public school teacher, father, grandfather and husband. He was previously active in labor struggles in the Postal Service and NYC Transit Authority.