Glen Ford's persona and dedication inspired analysis and created many friendships.

We first encountered Glen Ford during what he called the “lonely days.” The lonely days were those early months of the Obama presidency, when the jubilation of having a first Black president had rendered most Black people’s critical facilities completely useless and to even whisper a mild critique of Obama was to invite a torrent of scorn and opprobrium. Glen was one of “the 5-percenters,” as our mutual friend Kevin Alexander Gray called us. He was part of that small percentage of Black folk who did not fully support Obama. After Obama’s election in 2008, Glen, alongside the other contributors to Black Agenda Report, was a rare, persistent critic of Obama’s actual policies. He diligently scratched away at the progressive veneer to reveal a dangerous and reactionary neoliberal core; beyond the brown skin, he recognized the white soul of capitalism. During those difficult and lonely days Glen’s writing served as a lifeline for those needing critical analysis of imperialism, militarism, and racism, and of the meaning of Black liberation and self-determination.

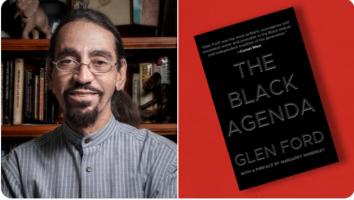

One was struck by both Glen’s voice, and his verse. Glen was a baritone. His voice was low, rounded out by years of smoking. In some ways it belied his physical presence: you did not expect this powerful sound from a slight, bespectacled, lightskinneded man, with his waspish goatee and his straight-ish hair gathered in a long ponytail. Be it in person or on the radio, he spoke with the solemn, deliberate, halting articulation of another era. His cadence forced you to reckon with every syllable spoken.

As for the writing, Glen gave us the vocabulary and phraseology to understand contemporary politics, especially of the right-wing contortions of the so-called left under the wheel of neoliberalism. It was Glen who gave us the phrase “the more effective evil” to describe Obama, dispensing with those who would fall back on the amoral pieties of a “lesser evil.” Glen also helped popularize the use of “Black misleadership class” as a way to understand the assimilated US Black political elite. It should be said, however, that he inherited that phrase from the rhetoric of his political forebearers: the Black Communists of the 1920s and 1930s who used the term “Negro misleaders” to describe reformist Black politicians.

Glen’s gifts as a writer were not merely in the coining of cutting phrases. Glen was a prose stylist of the highest order, a master rhetorician who combined a strict economy of words with a directness and clarity that revealed the stakes and consequences of politics and policies. There was no hiding behind language, no cowering behind muddled grammar, but there was certainly complexity—for what appears in the world as commonsense or obvious often veils the complex machinations of power. Glen’s writing cut through these veils with forensic precision, giving us the kinds of political economic critiques of capitalism that allowed him to see clearly the historical factors that gave rise to the charter school movement and the gutting of public schools, to understand what the 2008 bank bailout meant for the future of capitalism and democracy, to comprehend the revanchist white madness that elected Trump and murdered Trayvon. When so much of so-called Black left critique remains trapped by identity politics, or mired in a fetishization of race and racism as the primary defining factor of Black social and political life, Glen brought a knife-twisting critique of capitalism, militarism, and imperialism. It was a critique that could only come from being a socialist writing in the tradition of Malcolm X and the radical Dr. King.

We were eventually introduced to Glen in person at the 2010 Left Forum conference. From that first meeting, we would occasionally catch up with him when we visited New York City. Glen would take the train over from New Jersey and meet us at a downtown bar and we would spend a few hours talking politics and laughing at Glen’s stories of life in the military and in the media. During one of those meet-ups, the conversation turned to Haiti and U.S. interference in Haiti’s elections. “I wish I could explain to people what was going on,” Jemima told Glen. He responded that she should just write it up for BAR. Jemima laughed and argued that she didn’t know how to write like the contributors to BAR. Glen looked at us earnestly and said: “all you need is a hook and 800 words.”

Jemima’s first contribution to BAR was published in April, 2011 and soon, her commentaries appeared frequently enough that she was listed as a BAR editor and columnist. But it was difficult to keep up with the pace of publishing. Glen understood, and when she did send something in, he was happy to receive it. “Wonderful piece -- great overview,” Glen wrote about her 2019 piece on the protests in Haiti and the “imperial amnesia” of western coverage of these protests. “Nice to have your journalistic company, once again. Please make it a habit. Sincerely, Glen.” Unfortunately, she did not make it a habit. But we would be surprised when BAR would sometimes publish work that we had placed elsewhere, often in academic venues. How did Glen know about these essays? We hadn’t told him. But then we remembered that Glen read everything.

Even though we were not writing regularly for BAR, we stayed in touch with Glen. We invited him to Nashville to participate in the 2014 symposium Black Folk in Dark Times and to Los Angeles in 2018 for a forum on Peter’s newly-published book, Bankers and Empire. In Los Angeles, Glen asked for instructions on what to present and he wanted to go over his presentation with us beforehand. We were surprised by the request, and what seemed to be a sense of self-doubt behind it. He told us “this [academia] was not his world.” He said he didn’t understand how it functioned and the codes that governed it. Yet for us, Glen was among the greatest writers and sharpest minds we had ever encountered and we always wished scholars would try to learn from him.

Glen also told us something else during that visit to Los Angeles. “My mind’s not right,” he said with a wry smile looking over his glasses. He had been on dialysis for some time. He had to schedule appointments with the VA hospitals in California to ensure he could participate in our event. But there was a palpable sense in him that he was losing control. He had lost weight and seemed slightly disoriented. He told us that he had to make an intense effort to stay focused. It was at that point that we began to worry about his health. That worry accelerated from the fall of 2020 when he spoke of increasing serious health problems. At one point Glen lost his voice. The grand baritone was reduced to a forced rasp.

But Glen continued. The publication schedule of BAR continued, until the final months when his byline didn’t appear and the content of each issue became thinner and thinner. The only contact time BAR supporters had with Glen was during the weekly Black Agenda Radio segments.

The last time we “saw” Glen was on New Year’s Eve 2020. We had planned a Zoom meeting to discuss The Black Agenda Review, but Glen joined us with a bottle of cheap red wine after a day of editing and it turned into a couple of hours of animated conversation, storytelling, laughter, and libation. He said he was working on the page proofs for an edited collection of his writing. He was in good spirits and we all laughed when he admitted he no longer understood white politics. Glen had to join his family for the New Years celebrations and so our meeting reluctantly, for us, came to an end. We raised our glasses one last time and wished him a happy new year.

Cheers, Glen!

Sleep well, dear friend. We will miss you.

Peter James Hudson is a writer, editor, and historian who teaches Black Studies at UCLA. He is the author of Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean.

Jemima Pierre is a contributor to Black Agenda Report, the Haiti/Americas Coordinator for the Black Alliance for Peace, and a Black Studies and anthropology professor at UCLA.