A Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas in 1900. Source: Austin History Center

The Juneteenth holiday is an opportunity to delve into Black history in a serious way. Unfortunately, the designation of a federal holiday has trivialized Juneteenth's meaning and given license to scoundrels and cynics to get away with white washing the nation's crimes.

Juneteenth has a particular and special meaning if you’re the descendant of formerly enslaved people in the South, particularly Texas, where the holiday has been an official holiday and celebrated for decades. But between the opportunistic political whitewashing of the holiday by Democratic and Republican politicians alike, and the corporate marketing and vapid sloganeering surrounding it, what Juneteenth really means needs to be examined more closely.

First, it has always been strange that people who believe that Africans who were enslaved had an entire secret coded language for communicating among themselves, especially about escaping their enslavers, also believe that enslaved people in Texas somehow had no clue that the Civil War was over. That narrative is false, according to BAR Editor and Senior Columnist Margaret Kimberley who wrote in her June 2021 article “How Not To Celebrate Juneteenth” that, “Of course, Texans of all races knew that Robert E. Lee surrendered his armies in April 1865 and they knew that Lincoln was assassinated shortly thereafter. They had newspapers and the telegraph and letters from those who left the battlefield. Enslaved people were aware of anything that white people knew.”

But I would also point to the words of an ancestor, Felix Haywood, who was the son of slave parents bought in Mississippi and brought to San Antonio, Texas by Felix’ future master William Gudlow. Haywood and his siblings were all born into slavery, and worked as a sheepherder and cowboy before Union soldiers reached Texas in the summer of 1865. In an interview in 1937 with the New Deal Public Works Project, Mr. Haywood said: “We knowed freedom was on us but we didn’t know what was to come with it. We thought we was going to get rich like the white folks. We thought we was going to be richer than the white folks, ’cause we was stronger and knowed how to work, and the whites didn’t, and they didn’t have us to work for them any more. But it didn’t turn out that way. We soon found out that freedom could make folks proud, but it didn’t make ’em rich.”

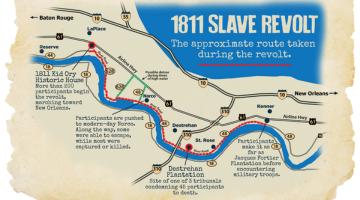

Now, I am going to discuss why freedom didn’t make Africans rich later in this article, but the immediate question of why it took two years for Texas to comply with the Emancipation Proclamation after the Confederacy surrendered needs to be addressed. And the answer is that there was no power in Texas to enforce it. Because Confederate forces in some states refused to surrender and give up slavery until the very last minute, and that was when Union forces showed up and forced them to. So the truth is that enslaved people of course knew the war was over and that they had fought for and won their liberation. But they also understood that the people who fought a war with their own government to keep Africans enslaved weren’t going to release them from 250 years of very profitable bondage just because they lost the war fair and square.

But there’s something else about Juneteenth that we need to understand to appreciate the full context of its meaning. The first statement of the proclamation, which is formally entitled General Order No. 3 issued by Union General Gordon Granger in Galveston, TX, does indeed state that “The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free…”, and goes on further to state that “...This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves,...” One could almost get excited about this freedom thing at this point if it weren’t immediately followed by: “... and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor.”

So let’s think about this. The formerly enslaved were supposed to just believe that the same people who fought a war to keep them enslaved were now suddenly going to not just treat them as equals, but would also now pay them fair wages for the work they just fought a war to keep forcing them to do for free? And who did not act on the knowledge that the Confederacy had lost the war months ago? And why would anyone trust the former enslavers to not only treat their former property as equal to themselves but to now pay them wages for work they had forced them to do for free over the past 250 years? I wasn’t there, but I bet my ancestors didn’t put much stock in trusting their former enslavers to suddenly do right by them in this regard. But if that weren’t bad enough, the final statement in the proclamation underscores a pernicious aspect of how the federal government, represented by the triumphant Union army, wasn’t really interested in actual freedom and equality between former masters and slaves as they claimed. It reads:

“The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

The government that supposedly went to war to end slavery really tried to tell the formerly enslaved to stay on the plantations that were the sites of their ongoing domestic terrorism, so the domestic terrorists who were their former owners could keep benefitting from their labor, even if they would have to pay for it now. Aside from the absolute absurdity of these torture sites being called the new freedmen’s home, if one is truly free, why put restrictions on whether and where one moves in that freedom?

It would seem from this announcement that our ancestors were not expected to exercise that freedom outside of a continued exploitative relationship between the people who profited off their free and forced labor for centuries. And the allegedly benevolent Union army and Northern politicians chastising people whose very offspring were worked like pack mules as soon as they could drag a bag behind them to pick cotton so that they would not be “supported in idleness” is absolutely galling. If anybody deserved to be idle for a few decades if they wanted to and be completely supported in it, it was the formerly enslaved, who worked under the whip until death to make the slave owners and the Northern industrialists and their families and their societies rich while the enslaved benefitted absolutely nothing! But instead, the liberals came down from the Free North with a reminder that they don’t tolerate lazy Negroes just like the Southerners who forced our ancestors to cook their food, raise their babies, clean their houses, and work their land so they didn’t have to didn’t.

Regardless of the attempts by the Northern white supremacist capitalists to keep the formerly enslaved tied to their former enslavers, I am happy to report that our ancestors did not do as they were told. According to BlackPast.org, “When the news came, entire plantations were deserted. Many Blacks brought from Arkansas, Louisiana, and Missouri during the War returned home while Texas freedpersons headed for Galveston, Austin, Houston, and other cities where Federal troops were stationed.” I’ll get to that bit about the importance of Federal troops in a minute, but humor me before I dig into that to examine what our ancestors did to celebrate their liberation.

Beginning in 1866 Black people began to hold parades, picnics, barbecues, and gave speeches in remembrance of the day that their enslavement ended in Texas. By 1900 the festivities had grown to include baseball games, horse races, street fairs, rodeos, railroad excursions, and formal balls. Recently on the ReMix Morning Show, I raged passionately against the recent wrongheaded and meaningless, if not outright politically opportunistic and corporatist, “celebrations” of the federal Juneteenth holiday that are devoid of any real historical context and modern political substance and utility. I do not mean to say that we should not celebrate at all, because our ancestors clearly did. But they did something more.

During these early celebrations, two important activities were carried out: first, the oldest of the surviving former slaves were often given a place of honor, so our ancestors were not ashamed of the degradation they triumphantly endured, they honored the resilience and resistance of the oldest survivors of it. Second, black Texans initially used these gatherings to locate missing family members and soon they became staging areas for family reunions. So these celebrations had a purpose - honoring those who survived and mending the bonds that were broken by what we survived.

And I have to ask, as an aside, is this where the tradition of family reunions began? I don’t know for sure, but I love it so much if it is. I suspect this might be true, since at Black family reunions to this day, you will likely find that many of us set aside time to call out the names of our family members who could not attend because they have gone on to glory, as Grandma Cornelia Jefferson would say, like my family did when she took her walk among the ancestors in 2018, and when my beloved husband Abdushshahid Luqman took his in 2021.

Anyway, back to the history… Let’s discuss why our ancestors leaving Galveston after that first Juneteenth and going to wherever federal troops were is important.

The Equal Justice Institute notes that the Union army - at this point recognized as Federal troops - remained in the South to ensure that Reconstruction-era amendments to the U.S. Constitution that abolished slavery, established the citizenship of formerly enslaved Black people, and granted Black people civil rights—including granting Black men the right to vote – were enforced in the former Confederacy.

But many white Southerners whose economy, society, and even culture were built upon the ideology of the supremacy of white people and the subjugation of Blacks opposed this new order, and many of them reacted violently to the requirement that they treat their former “human property” as equals and pay for their labor. Plantation owners and non-property-owning white mobs attacked Black people for claiming a freedom they never wanted our ancestors to have. Even with their presence in the South, in the first two years after the war, thousands of Black people were murdered. Imagine the bloodbath that would have ensued if Federal troops had not been present at all!

Well, we actually don’t have to imagine it because political protection of the formerly enslaved began to be rolled back as Congressional efforts were undermined by the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned laws that provided remedies to Black people facing violent intimidation. Then in the 1870s, Northern politicians began retreating from their commitment to equality and justice for Blacks, culminating in the Compromise of 1877 just 12 years after the beginning of Reconstruction. This is vitally important to the context of the idea of Juneteenth as a standalone marker for the freedom formerly enslaved people won, because it encapsulates how the political apparatus in this country has always operated in a bipartisan manner to curtail that freedom for their profit.

The 1876 presidential election featured Confederate sympathizing Democratic candidate Governor Samuel B. Tilden of New York and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, governor of Ohio, who wrote that he would bring “the blessings of honest and capable local self-government” to the South. Remember that this election took place during the Reconstruction Era, when as the Zinn Education Project describes it, “...in state after state…Black men, many of them formerly enslaved, gathered with white men, many of them poor and disempowered until Reconstruction, to rewrite the constitutions of the South. Starting in Alabama in November of 1867 and ending with Texas that opened its convention in June of 1868, multiracial assemblies met in Southern state capitol buildings — most built by the labor of the enslaved — to radically alter the political and economic landscape.” Most interestingly, the lesson points out that, “Also unlike the Northern constitutions, the South’s new laws protected Black civil rights. Blacks could now hold office, serve on juries, and several constitutions explicitly banned the kind of discrimination that would later characterize the Jim Crow South.”

So Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican candidate representing the party that was supposed to have been the stalwart opponents of slavery, was already signaling to the Southern white politicians and people that he would end this foolishness of Negroes and poor white people banding together to grow political power, and would bring instead “honest and capable local self-government.”

But by election night it was Tilden who had 184 of the 185 electoral votes he needed to win and was leading the popular vote by 250,000, but the Republicans refused to accept defeat and accused Democratic supporters of intimidating and bribing African-American voters to prevent them from voting in Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina, the only remaining states in the South with Republican governments. Democrats also accused Republicans of corruption in the same states, and two sets of election returns with different results were submitted. Meanwhile, in Oregon, the state’s Democratic governor replaced a Republican elector with a Democrat (alleging that the Republican had been ineligible), thus throwing Hayes’ victory in that state into question as well. Finally, in 1877 Congress set up an electoral commission to resolve the disputed election. Republicans then met in secret with “moderate” Southern Democrats to get them to not oppose the official counting of votes with a filibuster, thus ensuring a Rutherford Hayes presidency, and to accept the civil and political rights of African Americans, which the Democrats agreed to on the conditions that Hayes would appoint a prominent Southerner to his cabinet, support federal aid to build the Texas and Pacific railroad, and most importantly, to withdraw federal troops from the South.

His election now not opposed by Democrats, Hayes became president and he did appoint a Southerner to Postmaster General but did not approve a land grant for the Texas & Pacific railroad. Two months into his term, however, he did indeed do as the Southern Democrats asked and order federal troops removed from the last Southern state houses they were guarding Louisiana and South Carolina, allowing the Democrats in the former Confederacy to seize control in both those states, restoring their power all across the South.

The Compromise of 1877 effectively ended the 12 years of Reconstruction after the Civil War, when Southern Democrats’ promises to protect the civil and political rights of Black people were not only not kept, but the removal of federal troops from the South with the complicity of Republicans gave way to widespread disenfranchisement of and violence against Black people. From the late 1870s onward, southern legislatures passed Jim Crow laws that segregated Southern society through the middle of the next century with white mobs once again violently enforcing the white supremacist status quo, ending only after Blacks once again engaged in another liberation struggle, the Civil Rights Movement, culminating in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. There’s plenty to argue about the efficacy of those pieces of legislation, but because of the bipartisan Compromise of 1877, the legal subjugation of Black people in the South was extended for more than 90 years.

And this is why the freedom that people like Felix Haywood experienced made him proud but didn’t make him rich - because the social and economic subjugation under a new form of oppression of the formerly enslaved was necessary to maintain the exploitative relationship between our ancestors and this capitalist system that was built on their backs. And this timeline of enslavement to emancipation to Juneteenth to Black Codes implemented to limit the rights of freedmen in the South during Reconstruction and to the establishment of Jim Crow after was all designed to keep white supremacy the status quo in the South, certainly, but most importantly it was done to keep capitalism profitable off the continuation of the exploitation of Black labor forced to work for whatever the white supremacists in the South and the North decided to pay them, or else face violence and death that the Federal government did little to quell for nearly another century. Additionally, as punishment for being in league with the uppity Negroes thinking they were free and equal during Reconstruction, the capitalist class happily subjected poor white people to the same degradation.

So it’s nice that the US government made Juneteenth a federal holiday. But let’s never forget that this government, and both political parties in it, have always been complicit in compromising on not only our civil but our human rights and on any real acknowledgment, assessment, and recompense for what they denied us in the process, because their insatiable lust for the spoils of our exploitation - money and their political power - has always been more important than our freedom or equality.

Especially since it’s still being done to us in pretty much the same way today.

Jacqueline Luqman is a radical activist based in Washington, D.C.; as well as co-founder of Luqman Nation , an independent Black media outlet that can be found on YouTube (here and here and on Facebook; and co-host of Radio Sputnik’s “By Any Means Necessary”.