In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Christopher D. E. Willoughby. Willoughby is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the History of Medicine Health at Pitzer College. His book is Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

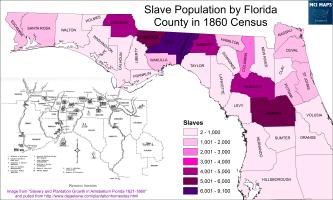

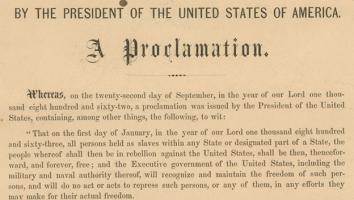

Christopher Willoughby: Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools is about the formation of racial expertise in U.S. medical schools from the founding of the first medical program at the University of Pennsylvania in 1765 up to the U.S. Civil War. This idea of the racial expert, I show, has deep roots in the nation’s medical institutions. Through research in medical faculty and student records, I found that in the decades leading up to the Civil War, many faculty and students had embraced an understanding of enduring, embodied racial difference, influenced by the theory of polygenesis—that each race was created as a separate species by the Christian God. Faculty and physicians built complex technical justifications to support inherited racial difference, measuring stolen crania from around the world and collecting data on race and mortality in colonial and enslaver societies. Finally, rather than being supplanted by Darwinism in the 1860s, many physicians merely adopted the causal narrative of natural selection while teaching that Black people were indefinitely anatomically distinct.

In our current moment and the longer historical trajectory of racism in medicine, my book has several important interventions, some of which will be addressed in later questions. Most critically, rather than focusing on the ideas of a few repugnant individuals, my research makes clear that the medical profession actively disseminated racial science through medical training. Rather than passive constructions like racism is in the DNA of American society that hide the active means of perpetuating racial essentialism, we must study how these ideas were spread through human and institutional action. Efforts at eradicating racial thinking from medicine, academia, and society more broadly then must acknowledge and target how institutions like medical schools embraced and still use eighteenth-century racial categories to study patient health outcomes. Moreover, these racial categories often mask the socio-economic determinants of health inequality.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

I think for those of us on the Left, my book should redirect the focus of our criticism toward institutions rather than individuals. In many respects, this book thinks about how doctors holistically became a sort of professional managerial class for “race relations”. Medical professionals and scientists played a unique role in that they were authorities on the meaning of the natural world and the human body. As the first U.S. medical schools were founded, racial difference quickly became a standardized part of the educational program. While there are significant changes since then, this general premise that race has medical meaning persists in the present. Likewise, despite some positive steps like the medical profession being significantly more diverse, racial theories and the use of racial categories in genetics research remains pervasive. The lesson here is that the problems of race in medicine are much bigger than issues of individual bias. Ending racism in medicine then requires significant institutional reforms to the curriculum as well as changing some research rules and regulations that passively and actively promote the racialization of medicine.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

For good reason, in the present, I would call skull measuring and racial science pseudoscience. Even most scientific disciplines today would agree with this, but I would implore readers to unlearn this term for studying the history of ideas that have since been discredited. Why?

Calling antiquated racial science in its historical context pseudoscience masks the complicit nature of scientists and scientific methods in spreading racial essentialism. In essence, when we describe these concepts as pseudoscience, we foreclose the possibility that the system of scientific knowledge production can create bad, factually suspect explanations of natural phenomena. Most prior historians of polygenesis in the U.S. have focused on pro-slavery politicians, and these politicians embrace of “pseudoscientific” arguments in defense of slavery. This framing tells us something about Southern politics, but it hides how racial sciences like polygenesis have had homes in elite, northeastern institutions like Ivy League medical schools or scientific academies. This political history framing makes medical, racist theories appear cartoonish and outside of the bounds of scientific knowledge. What my book reveals is the opposite. In mainstream antebellum science and medicine, politicians found a convenient argument to protect the institution of slavery. Thus, I hope my readers unlearn this term when thinking about the history of science. It does not mean we should abandon science or scientists, but we should scrutinize their findings ourselves and assume they are shaped by and shape broader social terrain.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

Well, at its core, I hope this book can shed light on the role of institutions in theorizing and promoting racial essentialism. So, on the one hand, Masters of Health provides a sort of origin story for scholarship like Dorothy Roberts’s book Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. Like Roberts reveals about the present, in the antebellum period, medical faculty found racial theorizing profitable. In the case of polygenists Samuel Morton and Josiah Nott, they gained international fame through writing racial science monographs. On the other hand, the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school had a student body that was more than fifty percent southern. Professors were paid per student. Thus, they had a profit-motive to teach a curriculum that would be useful for physicians practicing in plantation districts. Despite a growing sectional divide over slavery in the antebellum period, southern students knew they could receive a racialist education in the North.

Second, my goal is to illustrate how these racial essentialist theories naturalized profoundly unequal conditions among people. In this sense, I am directly building on Marxist scholars like Adolph Reed Jr. and Barbara Jean Fields, who have analyzed the race concept and the underclass myth as ideologies that naturalize and justify unequal conditions and exploitative labor regime. In medical education, white students obtained some invisible psychological “wages of whiteness”, but the race construct’s core function was to legitimate a hierarchical labor system. Through racial theories, elites created a scientific framework that obscures their responsibility for inequality in health and wealth.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

Wow, that is a big question, but I am going to stick to the field of racial science and medicine. The two books that have pushed me to think about my research differently are James Poskett’s Materials of the Mind: Phrenology, Race, and the Global History of Science, 1815-1920 and Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. These books have greatly influenced my next project which is a global history of a racial skull collection at Harvard Medical School’s nineteenth-century museum. In the case of Poskett, what makes his book unique and interesting is how he focuses on the critical role of material culture and global commerce in making racial science possible. In Poskett’s framework, race science is not just the product of white men thinking, but instead was built upon the material networks of global capitalism. From materials mined to make plaster casts of heads to intellectual exchange built through books and journals, Poskett’s intellectual history is shaped by material culture and conditions around the world.

Cooper Owens on the other hand highlights the individual in her study of how enslaved women were experimented upon but also became trained and worked as nurses to create novel gynecological surgeries in the South. Cooper Owens emphasizes various methods and routes to humanizing and narrating the lives of those subjected to science. These books have directly influenced my new project, which will be a series of short histories of people whose skulls were stolen and housed at Harvard. Like Poskett, I aim to situate their lives in a global array of networks and events in the history of imperial and commercial expansion. Learning from Cooper Owens, I will also focus on the life stories of these individuals.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.