African Stream is an anti-war, anti-imperialist video and text website based in Nairobi, Kenya. I spoke to its founder, Ahmed Kaballo.

Ann Garrison: I love African Stream. Can you tell us how you got started?

Ahmed Kaballo: African Stream was an idea I had after working as a journalist for many years. I was always trying to pitch stories about Africa, and even when I worked for anti-imperialist media, they would tell me, unfortunately, that people just weren’t interested in Africa, that their eyes were glued to the Middle East, North America, South America, and Europe.

I've always been passionate about Africa, so I was determined to prove that mantra wrong. I'm an African person, my future, my past and my present are in Africa, and I wanted to create an anti- imperialist platform focused on Africa, but with a global audience, not just Africans. The majority of our audience are Africans, but we also appeal to anti-imperialist and anti-war people from all over the world who want to build a broad movement.

AG: Are you yourself from Kenya?

AK: No, I'm from Sudan, but I went to university with a few Kenyans.

I knew that for me to set up an African media outlet with any credibility, it needed to be based somewhere on the African continent and operated by Africans, from the camera operators to the editors. So then it was a question of where to work and we decided it had to be an English-speaking nation since we were going to produce mostly in English to reach the broadest audience, though we are also now producing some content in French.

So I just basically created a chart of the important things for choosing a site for this project. They were:

- Press freedom

- Safety, particularly because I was planning to relocate here with my family

- Internet speed and infrastructure, and

- Connectivity to other parts of Africa that we might want to fly to

There were a few options, but Nairobi, Kenya, came out on top, and I've got a great team here.

AG: How is African Stream structured?

AK: There's me as the editor in chief. Then we have two managing editors beneath me, and we have two output editors who fact check and check the structure of every story. We're always trying to compete for the attention of people whose attention spans are shrinking by the day. The two managers and I do the final check.

In the Kenyan office, we also have four full-time journalists. We have three editors, and three camera operators. We work with two freelancers in Burkina Faso, two in the US, and others around the world.

AG: And how do you decide what and when to webcast and post text?

AK: Most of the team in Kenya works from 8 am to 5 pm. And then the freelancers work from 10 am till 7 pm. And we have a couple of people in the Kenyan office who work from 2 pm to 7 pm. So we treat it much like a nine-to-five from Monday to Friday, but we also schedule people who work on the weekend.

We’re constantly looking for stories and doing research to find out what's going on on the continent and in the diaspora.

Our full-time journalists and freelancers are always pitching stories, and I'm also constantly pitching stories to journalists.

We try to do about ten posts a day. On the weekend, that drops down to about six on Saturday, six on Sunday. We're currently just trying to keep that content going, trying to keep people updated. We get messages from the audience asking why we’re not covering this or that, and this is actually very helpful because it's quite a challenge to stay on top of what’s happening in Africa’s 54 nations and in the diaspora without having journalists in each country. The audience alerts us to things that we need to look into.

Another thing that helps us is that a lot of the journalists we work with also come from a community organizing background. So beyond the reach of the journalists that we have, we are also connected to many different community groups in different countries.

So sometimes they may bring our attention to something that the mainstream media is reporting in a certain way, but that we need to get deeper into, to determine what the real story is.

AG: So you consider your beat the Black world worldwide?

AK: Exactly, from the start, and we've been very consistent on that. You know, we're following in the footsteps of Malcolm when he started the Organization of Afro-American Unity and lobbied African states to support his charge against the United States for human rights violations. We are one people, our struggles are connected. And only once we connect those struggles and connect with each other are we really ever going to be successful.

AG: And do you have an editorial policy, a way in which you determine whether or not you're going to take an editorial stance or a perspective you’re going to report from?

AK: Yes, we do. And the editorial policy is constantly under review. We all have a meeting every Thursday at noon. We have an editorial policy and perspective that we've devised over time, but then there are always tricky, seemingly contradictory topics that we need to discuss. For example, what was going on between Venezuela and Guyana over oil rights. That was one of those topics that needed to be explored. We had many conversations with different people and tried to figure out what was going on, because broadly, as leftists, socialists and Pan Africanists, we support the Bolivarian revolution and the Republic of Venezuela particularly, but when that disagreement arose, it didn’t look good.

So we tried to hold off before jumping into the story. We consulted and read many sources, including Black Agenda Report, to figure out what was going on. By the time we had done that it seemed to have settled down, and they seemed to have reached some sort of agreement.

We have a very clear editorial policy on support for the self-determination of Western Sahara and its freedom from Moroccan occupation.

We also have an editorial stance on what's going on in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). We see that as Western aggression carried out by proxy states Rwanda and Uganda. We think there is always war in DRC because it’s so wealthy. For the cheap extraction of its resources, there needs to be a constant state of destabilization. Rwanda is there under the guise of taking out what they call Hutu extremists who committed genocide in Rwanda, but even if that were once true, that genocide took place 30 years ago, so now it’s just Rwanda’s excuse.

We take a very clear position on Israel and Palestine. And we oppose settler colonialism in all of its forms. We ask why Israel has support in Africa, and we did a story on evangelical churches in the United States and their support for the evangelical, Zionist movement in Africa.

AG: I watched that interview you did with the rapper and scholar Lowkey, who said that the repressive technologies and strategies developed by the Israeli state could be turned on Africans.

AK: Yes, Lowkey’s a friend of African Stream and we were glad to have him on.

We also took a position on the coup in Niger that was informed by somebody on the ground, speaking to people in the army and in the streets. We asked why there was so much enthusiasm for these men in military uniforms.

We support the alliance of Sahelian states–Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. That’s the kind of unity we want to see more of on the African continent, more pooling of resources, more mutual defense.

People criticize the fact that Russia is in Africa supporting the security process there, but our argument is that there would be no need for Russia or anyone else if we united and pulled our resources together to defend one another and speak with one voice on the global stage.

AG: And how is your audience growing?

AK: Six months ago the greatest number of people following us and engaging with our content were from the United States, but now I think Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa, is first, and the United States is second. East Africa as a region is third. Our audience used to be mostly male but now it seems to be at least half female. On our YouTube channel, our audience was predominantly from India, though that’s changed over time. I can only guess that there are a lot of African students in India. Now South Africans make up our largest audience on YouTube.

We keep building our audience by producing a steady stream of high quality, reliable, consistent content. If we make a mistake, we always put in a correction.

Even over Christmas, when we took a couple of weeks off, we made sure that we posted around eight times a day.

We try not to miss any of the big stories even if that means our social lives suffer.

We've been operating for about a year and a half now, and I remember that during that first half year, it seemed like nobody was watching. You know we’d get 10 likes and two comments on a post, and one of the comments would be from one of our wives saying, “Good job.” And we’d ask ourselves whether it was worth it.

But eventually more people started liking and sharing our content, and the shares helped us a lot.

AG: I've been sharing your content on my Twitter page, and I’m going to start sharing on Facebook. It's great stuff and there’s nothing else like it. It's so needed.

AK: Thank you.

AG: As an American who tries to understand and write or broadcast about Africa, I find it's so under-reported that I often struggle just to find a starting point. I have to ask myself how much someone who might be reading or listening might know.

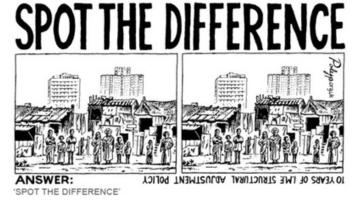

AK: In my circle of friends and family, I used to be that guy that they're considering woke, who’s always preaching about serious subjects, including Africa, to people who don’t consider themselves “political.” So when we started to create African Stream, we wanted to grab those apolitical people as well, so that we wouldn't just be speaking to ourselves. That's why we’ve tried to create a lot of short content. We often try to condense it into one to three minutes because longer pieces don’t have the same reach.

We're also trying to do more skits as a way of grabbing the attention of those apolitical people. William, a young guy that joined us as an intern, just did a brilliant skit mocking Michael Rapaport in Israel, where Rapaport was saying, “You guys keep talking about apartheid? Where's the apartheid?”

William went to Karen, a posh suburb in Nairobi, and asked, “Where are the slums in Kenya? I don't see any. Where are the slums?”

AG: I find your text posts are very digestible; it’s not that they don’t go deep, but they have a concision that people can stick with and understand.

I only have one request. You recently had that text piece about M23 in the DRC and you cited sources that went into it all in much greater length, but the long URLs in the graphics weren't clickable, and I couldn't copy them either, so I’m hoping you’ll add them.

AK: The image wouldn’t allow you to copy and paste the URL?

AG: No, and I really wanted to read the sources. Short is good, but URLs are good for those who want more.

AK: Thanks. That’s good feedback. I'll make sure the person who posted that adds to it.

AG: You've got a lot of labor going into this and no advertising. Do you have any funding, or is this all a labor of love?

AK: We got some funding from some Africans. Our pitch at the beginning was that you're investing in this humanitarian organization and that humanitarian organization, but the problem isn't, you know, aid. The problem is perception. So if you really want to help the continent of Africa, you have to invest in changing the perception of Africa, both on and off the continent.

So we got some funding, but it’s running out, so we're about to launch a fundraiser. The plan was always that we’d have funding in the beginning, then we’d create a product that people would value, and once we have a big enough audience, we’d say to them, “Listen, you've been following us now for up to a year and a half. For this to continue, we're going to need your support.” And hopefully, you know, people are invested enough in the product that they will do that. If our direct messages are anything to go by, then they will, but who knows?

AG: Who was the original funder?

AK: We got funding from different sources. Private individuals, and because of the stuff that we report on, they don't want to be named. We actually lost one of the funders from Nigeria because he wasn't happy with our coverage of what was going on in Niger. And that did affect production. We had to let a few people go.

AG: So now you'll be doing a GoFundMe and/or a Patreon page?

AK: Exactly.

AG: Now lastly, we’ve touched on the DRC, but I’d like to know if there's anything further that you'd like to say about that and about Haiti, one of the other most long suffering corners of the African world.

AK: OK, I'll start off with Haiti. We've been covering Haiti quite a lot from very different angles. We had a reporter who managed to find out where Ariel Henry was going to be and ask a question at an event where questions were not invited. And what's going on in Haiti is very sad. The plan to deploy Kenyan police as part of a US/Western occupation there has damaged Kenya’s reputation on the global stage, especially among Africans.

There’s this widespread misperception that because there’s a so-called gang problem in Haiti, the solution is US-sponsored intervention, and we reject that. We know that the United States has essentially occupied Haiti for the past 20 years, stolen many of its resources, installed a dictator, and actively destabilized it. The US removed its only democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, and it’s the US that will be leading this new military deployment there, even if Kenya ultimately takes part. We actually have someone on the ground in Haiti, and we began covering the situation as soon as we started African Stream.

And the sentiment in Port-au-Prince is the same as the sentiment in Nairobi. Haitians don’t want Kenya to intervene, and Kenyans don’t want to intervene. This is a project of imperial elites and those they’ve compromised.

Haitians want weapons to stop flooding into Haiti from the United States, whether to the government or to armed groups in the streets. They're all coming from the same source. If the United States wanted to really help the people of Haiti, that’s how they would do it. They would stop the arms from getting into the country.

Now DRC. The DRC needs everyone's attention and everyone's support. The only real way that we're going to stop the crisis in DRC is to intervene in the supply chains going from DRC to the industrialized world.

A lot of people fall into the trap of just blaming Rwandan President Paul Kagame for everything, and we criticize both Kagame and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, but unless we expose the supply chain, and all those benefiting from the ruthless resource extraction, then there'll just be other figures destabilizing the DRC after Paul Kagame and Yoweri Museveni are dead. So we really need to make sure that there's more accountability from these companies like Tesla, Apple, and Glencore with regards to this resource extraction, because that's what's fueling the instability. If there was nothing underneath the ground, apart from the dirt, DRC wouldn't be in the situation that it's in right now.

AG: Okay, is there anything else you'd like to say?

AK: Only that we’re huge fans of Black Agenda Report. You guys do fantastic work.

AG: Thank you.

African Stream can be found on the Web, Twitter, Facebook, Tiktok, and YouTube.

Ann Garrison is a Black Agenda Report Contributing Editor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. She can be reached at [email protected]. You can help support her work on Patreon.