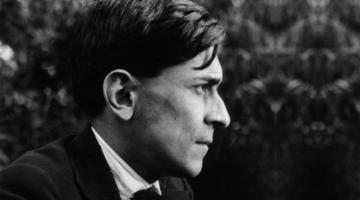

William Bass pictured with two railroad workers on his Monte Coca line in Hato Mayor, Dominican Republic. Source: William Bass, Thirteen From the Front: A Memento. 1909.

From the moment the first colonizers arrived in the Caribbean, the West has treated the region as a treasure chest for resource extraction and labor exploitation.

In January 1936, William Louis Bass, an American sugar industrialist from New York, submitted a 16-page proposal to Haitian president Sténio Vincent. It was for the transformation of La Gonâve, a Haitian satellite island, into a residential and commercial haven for foreign industrialists in what he called “the Garden of Eden.” Per his proposal, the plan would require an authorization of $25,000,000 in American capital, tax exemption for the businessmen that would reside there, and the development of an isolated portion of La Gonâve into a “resort or playground for wealthy foreigners, natives, and naturalized foreign-born citizens.” Bass had good reason to believe the Haitian government might agree to his plan. From 1915 to 1934, the Republic of Haiti had been victim to a brutal U.S. military occupation, and in its aftermath, the specter of American economic dominance over the country still loomed large.

Bass was not unfamiliar with the Caribbean terrain (or tax exemption for the wealthy). He was born on a sugar plantation in Alacranes, Cuba in 1865, where his father, Alexander, worked as an engineer on the estate of slave owner Don Juan Poey. From about 1887 to 1912, Bass owned multiple sugar plantations in the Dominican Republic, including the Ingenio Consuelo, the largest sugar mill in the nation at the time, and was consistently offered concessions on import and export duties by the Dominican government. After the U.S. acquisition of Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War, Bass expensed $750,000 in capital to incorporate the Humacao Sugar Company, taking advantage of the absence of tariffs between Puerto Rico and the American mainland. The exploitation of Caribbean land and labor, to Bass, had been a career, and throughout it, he consistently championed the expansion of American imperialism to facilitate his commercial pursuits. He was a staunch supporter of the 1903 Platt Amendment that tied Cuba’s sovereignty to American control, and advocated for an extension of that policy to the Dominican Republic. On his sugar mills, he exploited the labor of Afro-Caribbean subjects of the British West Indies, paying them only 50 cents to $1 per day, and housing them in squalid, inexpensive settlements known as bateys, neighborhoods meant for migrant sugar workers in the Dominican Republic.

Bass’ proposal for a “free zone” in La Gonâve never quite materialized—but the idea of the Caribbean region as a Garden of Eden for wealthy Westerners looking to both exploit labor & experience tropical paradise indeed prevailed. In fact, it is today’s modern reality. This exploitative dynamic is one that the esteemed Antiguan writer Jamaica Kincaid captured cynically in the opening pages of A Small Place. She takes the reader, the tourist, from the international airport of her native country into its emblematic sites—its roads (badly paved), its buildings (repairs pending), the Prime Minister’s Office, the Parliament building, the American Embassy, etc. Kincaid’s tourist notices that Antigua’s cars look brand new yet sound awful, that merchants & businesses deal in American currency and not their own, and that the natives do not take kindly to tourists. Because every native, anywhere in the world, would like an escape from the onerous toil of their day-to-day life. But, as Kincaid reminds us, most natives in the world are too poor to go anywhere. “They are too poor to escape the reality of their lives,” she says, “they are too poor to live properly in the place where they live, which is the very place you, the tourist, want to go.”

Alexander and William Bass were two of the earliest progenitors of a form of economic exploitation enhanced by American dollar diplomacy in the post-emancipation Caribbean. The presence of American corporations holding a monopoly on Caribbean industries was enabled by the U.S.’s early 20th century Monroe Doctrine policy, predicated upon the idea that the Western Hemisphere was America’s playground. The internationalization of U.S. banking also helped enable such commercial control, with American bankers financing American commercial pursuits in Latin America & the Caribbean, a phenomenon well-documented in Dr. Peter James Hudson’s Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean. This rise in American dollar diplomacy and the importation of American finance capitalism into the Caribbean was accompanied by a rise in Caribbean tourism. From the end of the 19th century up to World War II, over 100,000 European and American tourists would vacation in the Caribbean. Thus, the plan that Bass had proposed for the island of La Gonâve had not been a deviation—the industrialist was merely trying to combine a more classic economic domination with a sort of new form of residential tourism.

In the contemporary world, this combination of Western tourism and economic extraction persists in the Caribbean. It is not merely a remnant of a dying colonial past but an actively maintained present condition that plagues the Caribbean region. Caribbean economies are heavily reliant on tourism, and extractive commercial industries plague the region. In the Dominican Republic, for example, tens of thousands of sugar workers, many of them stateless, toil under the sweltering heat of the tropical sun, cutting sugar cane for the profit of American-based companies such as the Florida-based Fanjul Corp. In the summer of 2021, the National Workers Union of Jamaica protested that workers in the nation’s tourism sector were being exploited “to the point of slavery” in the midst of deadly COVID-19 infection spikes. The following year, Haitian garment workers exploited for the benefit of fast-fashion companies such as H&M and JC Penney, crowded the streets of Port-au-Prince in a strike that called for an increase of wages from $5 USD per day, to $15 USD per day. For the nations of Guyana and Venezuela, ExxonMobil’s 2015 discovery of 11 billion barrels of oil in the Essequibo region has sparked a border conflict escalated by American imperialism. All the while, the company is usurping over 65% of Guyana’s oil and gas workforce. Chevron acquired the Hess Corporation for $53 billion last October for a share in the Guyanese oil pot—a transaction that may pay the nation of Guyana as little as $100,000.

Imperialism, as shown through the aforementioned examples, has continued to rear its ugly head on the Caribbean people. As the work of the assassinated Guyanese historian Walter Rodney is increasingly called to the fore, we should consider his writing on the considerations of Third World development and the folly of pseudo-development through extractive forms of industrialization:

“Imperialism has been able to circumvent the criticism that it reduces the Third World merely to primary production. The international bourgeoisie and their agents have been able to start ‘industrialization’ of a sort within Third World countries. Looking at the development plans of every African nation, one finds that a beer factory will usually figure number one or number two on the list. Building a beer factory is considered as the first step towards industrialization. Quite apart from the fact that I don’t know of beer as having developed any nation, one has to realize the fallacy on which the claims are based. ”

In the Western Hemisphere, the Caribbean region has for centuries been a site of imperialist extraction and labor exploitation from the eras of slavery and colonialism through independence and neo-colonialism. In the imperial core, especially in the U.S. where multinational firms dominate Caribbean industry, international class solidarity should and must consider the Caribbean. The sustenance of the capitalist system is inextricably tied with the maintenance of imperialism—one cannot exist without the other, and both systems are inextricably concerned with the Caribbean region.

Joseph Sturgeon is a student organizer with the Kwame Ture Society based at Howard University in Washington, D.C. An aspiring historian of the Caribbean, he writes on racial capitalism, political economy, and the impacts of imperialism.