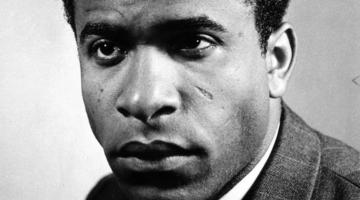

Kwame Ture reminds us that the Black university is a place of contradictions – and a potential site of struggle.

The announcement that Howard University was awarded a $90 million contract to create a Department of Defense research center – the first for an historically Black college – brought a torrent of disbelief, disgust, and scorn from many corners of the Black interwebs. Sure, there were folks who unapologetically thought that Howard should take the money, grab the bag, seize the loot; there were folks who made the straightforward, if backward, claim that universities need money and they couldn’t choose where they got it from. But mostly, there has been anger at a sense that a prized Black institution of higher learning had not simply sold out, but was also about to sacrifice all of its one-hundred-and-fifty plus year mission and history.

Founded in 1867, Howard was known as “the capstone of Negro education.” It differed from institutions like Tuskegee and Hampton both for its federal charter, and for its self-conscious role in educating the upper realms of the Black elite and professional classe. Yet like Tuskegee and Hampton, and like other HBCUs, it has long had difficult financial fortunes, a fact attenuated after predominantly white institutions integrated, drawing both Black students and, eventually, Black donors. It is a situation embodied by a primary contradiction in Howard’s life: while student dorms are falling apart, and student aid is nearly non-existent, the university has found a way to lure highly-paid, megawatt star professors, ostensibly (if perhaps paradoxically) to aid in fundraising.

Arguably, Howard’s financial crisis parallels a crisis in its mission. This crisis is embodied in the question: What is the purpose of the Black university? It is a question that has recurred since Howard’s founding, seen in the student protests of the 1920s (when students protested compulsory military training) and the 1960s. It’s a question that also animated discussions in a number of special issues of Black World/Negro Digest at the beginnings of the birth of Black Studies. The Department of Defense (DoD) contract, and Howard’s new role as the capstone of military research for a network of HBCUs, returns us to that question in alarming ways. It is a situation that evokes what Walter Rodney once called “the juicy contradictions” of the political economy of Black higher education in the service of US imperialism. Rodney writes: “Rockefeller finances a chair on African history from the profits of exploiting South African blacks and upholding apartheid! Black revolutionaries study African culture alongside of researchers into germ warfare against the Vietnamese people!” With the DoD contract who knows what nefarious activities will be paired with the Black college experience? Who knows what juicy contradictions Howard faculty and students will now face in their pursuit of knowledge for Black liberation? Is the pursuit of knowledge at an HBCU still for Black liberation?

Howard, of course, has attracted and graduated many of our most important intellectuals and activists. The great pan-Africanist Kwame Ture was a student at Howard in the 1960s, when he was still known as Stokely Carmichael. His autobiography, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael, has a chapter called “Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite.” Ture acknowledges the impact of the university on his life, while conceding its contradictions. He lists his inspired encounters with the faculty — including Rayford W. Logan, Sterling Brown, Toni Morrison, E. Franklin Frazier, W. Leo Hansberry, Chancellor Williams, Frank Snowden, Owen Dodson, Arthur P. Davis – while describing his protests against the ROTC. Ture paid respectful homage to the Black University, while demonstrating that its relevance and excellence could only be preserved through student struggle. We reprint an excerpt from Ready for Revolution below.

Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite

Kwame Ture

Howard University would open up vast new horizons for me. No doubt about that. Without question, I received a unique education there. And no question, it was qualitatively and substantively different from any education I could possibly have had at Harvard or anywhere else in the world.

At Howard I was educated as much by my fellow students as by the faculty; as much from the location of the school, the friends I made, and the spirit of the times as from anything to be found in the curriculum; as much from the character of the administration as from the quality of instruction; as much from the movement as from the university. But educated I was.

Because in our time-the opening four years of the 1960s-Howard University was an extraordinarily interesting place for any young African to be who was not totally brain-dead and who was concerned with his people and their struggle. And both conditions were to be found among students at Howard.

Howard presented me with every dialectic existing in the African community. At Howard, on any given day, one might meet every black thing ... and its opposite. The place was a veritable tissue of contradiction, embodying the best and the absolute worst values of the African-American tradition. As Junebug Jabbo Jones (may his tribe increase) loved to say, "Effen yo' doan unnerstan' the principle of eternal contradiction, yo' sho ain't gonna unnerstan' diddly about Howard University. Nor about black life in these United States neither."

What's more, in every significant regard the Howard experience was the diametrical opposite to that of Bronx Science. Now, I am not putting down either school. I really enjoyed both, and I was, for good or ill, profoundly influenced by both, though in different ways. One obvious difference is age. I entered Science at fourteen and Howard at eighteen. But more than that, in terms of institutional culture, the character of the student population, the general social and intellectual ambience, it is impossible to imagine two more different schools.

Each school had a well-developed sense of its uniqueness. Each had an equally strong view of its institutional mission and constituencies. But nothing about these was even remotely similar. They could have been in different countries. Indeed on different planets. Which, if you think of it, is a reflection not on those schools, but of the country. Science had its face turned rigidly back toward Europe, while Howard, no matter how much some resisted or sought to play it down, had turned its face, however tentatively, toward Africa.

Howard's most egregious image in the African community was as an elitist enclave, a "bougie" school where fraternities and sororities, partying, shade consciousness, conspicuous consumption, status anxiety, and class and color snobbery dominated a student body content for the most part with merely "getting over" academically.

Was this true? Certainly to some extent, but while this aspect was for some reason very visible, it was, give thanks, by no means, the whole story. Nor even close to it. There were, of course, the status-conscious, overindulged, whiskey-drinking children of affluent black professionals. But at least half the American students were from the South, and the great majority, whether from North or South, were poor, the children of black workers and strivers and most usually as in my own case, the first in their immediate family to attend college. So, if they aspired to the attitudes, behavior, and values described above, they hardly had the means to afford them.

Adding to which a hefty percentage greater than in any other American university were "foreign" so-called. This meant Africans from either the English-speaking Caribbean or mostly anglophone Africa. These students tended to be slightly older, well prepared, and motivated academically, somewhat more cosmopolitan in outlook, and every bit as poor as the Africans born in America. So that when I checked into the new Men's Residence Hall in September, my roommate was Gurney Beckford, a small, dark, exceedingly earnest young man from the hills of Jamaica. Housing probably saw my place of birth as Trinidad and so stuck me in with someone else from "the islands." It was fine with both of us, we got on great. Gurney is still a good friend.

The new Men's Residence Hall was formally named Drew Hall that year. "Drew" being Dr. Charles Drew, the African (American) physician whose pioneering work in hematology isolated plasma and made blood transfusion possible. Dr. Drew had done this work while on the faculty of the Howard Medical School. According to the oral tradition on campus, Dr. Drew, whose work had saved countless American and other lives during WorldWar II, and who had transformed the entire practice of Western medicine, bled to death after a car accident in the South where he was denied the prompt medical attention he had made possible and that might have saved his life. I'm told that this account has recently been challenged, but that is how it was told on campus when we were there.

I expect the Trinidadian birthplace was also the reason I soon received a letter summoning me to "the foreign students' orientation."

Of course I looked like, dressed like, and talked like a black New Yorker. But I could slip at will into the Trinidad idiom and accent of my parents and their friends. A first-generation immigrant kid who had not forgotten the language of the old country.

But my freshman dorm was an extraordinary place English-language wise. There were brothers from Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, every state of the old Confederacy, and areas urban and rural. There were my home boys from Harlem, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, and brothers from Detroit, Philly, Roxbury, South Side Chicago. All Africans born in America, but what a diversity of slang and sound. Also, by the end of my first week I had begun friendships with brothers from Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad, Antigua, the Bahamas, and on and on. I had also met Igbo and Yoruba men from Azikiwe's Nigeria, Fanti and Ashanti men from Nkrumah's Ghana, and Luos and Kikuyus from Kenyatta's Kenya. All three heads of state had a personal relationship with Howard.

During 1960 a wave of African nations had attained independence, as would Jamaica, Trinidad, and a host of smaller territories in the east Caribbean in the following two years. Later, the Osageyfo, President Nkrumah, would correctly characterize this as being mere "flag independence." But to us at Howard that fall, blithely unaware of the looming threat of neocolonialism, it was an exciting, heady moment rich in promise. All Africa would be free. You could see it happening. Free to choose judiciously from the riches of its own traditional wisdom and the best of Western achievements to give the world a new definition of modernity and a higher humanism. Africa, we were fully confident, would solve the great human problems that continued to bedevil European civilization. We were so sure then, so optimistic, that we would live to see that. Now, I think it will take longer.

It seemed like almost monthly a new African embassy would open up with suitable dignity and fanfare. The diplomats always reached out to their nationals studying at Howard, who in turn invited their "American" friends. So we got accustomed to going with our friends to any number of annual national independence day celebrations at various African and Caribbean embassies. That time and place had a tangible, intoxicating air ofPan-African motion and internationalism. It was soul stirring.

The administration at Howard, and to a certain extent the faculty, would reflect many aspects of the massive contradictions underlying the relationship between Africans in America and white America.

On one hand, the school pointed with justifiable pride to its historical role in the progress of the race. Not just by educating "Negro leadership" but claiming an honorable role at times in the actual struggle. For example, most of the lawyers in Brown vs. Board of Education were Howard Law School products. Outgoing president Mordecai Johnson had been a forthright advocate for African civil rights. President James M. Nabrit Jr., who replaced him the year after I entered, had been part of the legal team arguing Brown. So he came from an activist legal tradition.

The Howard Choir (in the tradition of the Fiske Jubilee Singers, which, in the 1880s, had rescued that school financially by famously touring European capitals singing the powerful music of their slave ancestors) could make you weep and exult with those same "Negro spirituals." Still, the dean of fine arts was so unreconstructed and unapologetic an Afro-Saxon that he absolutely forbid jazz in any form, not even from the elegant and musically sophisticated "Duke of E," in Crampton Auditorium ... as long as he would be dean.

Howard was the only historically black school in the entire nation funded by the federal government. My position was, in simple justice, all black schools should have been, so that was no real cause for gratitude on our part. But that was not, could not at least publicly be, the position of the higher administration.

For some curious reason the congressional committees that controlled the university's budget seemed to attract a disproportionate number of Dixiecrat politicians. These Southern Democrats, the political beneficiaries and institutional protectors of white supremacy in the nation, were aptly described (some of them, anyway) as "the most mean spirited, foulmouthed crackers who ever bought a fool's vote with whiskey." And they did not position themselves on those committees out of any sudden rush of goodwill toward black folk.

So annually Howard's president had to walk a narrow line drawn by the whim, caprice, or outright malice of these Dixiecrats. At budget time, a tangible mood of anxiety, high or muted, depending on the perceived mood of the Congress, seemed to emanate from our administration building. I don't remember a student who was not aware of this reality. And I don't know one that did not resent it. It was almost always one of the first things a new student heard: "Looka here, Uncle Sam pays the bills. Best you never forget that and always present yourself accordingly."

I can now sympathize with the fundamental difficulty of our administrators in having to go hat in hand to those racists. Those black men, when all was said and done, did have the responsibility to protect and advance as best they could the school's interests. But on campus that constraint translated into a series of attitudes, rules, and injunctions calculated to prevent any activity on the part of the students that was likely to offend "powerful white folk." These filtered down to us via the Student Activities bureaucracy, with whom we were, consequently, constantly at war.

As you might well imagine, we in NAG [Nonviolent Action Group] took a slightly different position. Inasmuch as this nation had enslaved Africans and continued to discriminate against them, thereby crippling them educationally, we felt that the least the nation owed the African community was excellent resources by which to educate ourselves. Educationally, we felt America owed us many more than one federally supported school. As a matter of historical obligation, not charity.

So far as "upsetting powerful whites" was concerned, we felt no obligation to be "nice" or "neat, clean, honest, and polite" as the formula went, just to get the budget. We felt, especially as we grew more confident in our organizing skills, that we students could organize effective pressure inside the nation's capital, in international forums, and before the world media, to ensure that the U.S. government met its obligations to black education. We understood that the Howard administration would need to stay aloof publicly but at least they should not hinder us. The world was changing, wasn't it?

But this was never the position of the administration. Which is why NAG was never a recognized student organization at Howard. Every year we petitioned. Every year the Student Government and the students supported us. Every year the initiative ran into the most skillful, stubborn, and barefaced obstructionism from the Student Activities bureaucracy. Processes were arbitrarily changed, suspended, or ignored; committees dissolved or simply did not meet all year; or else meetings were summarily adjourned before a final vote could be taken.

We would be furious, roundly denouncing the "handkerchief-headed, plantation overseer mentality" of the Division of Student Life. But you know something ... I'm now prepared to see a certain method in their madness. As the spiritual says, "You'll understand it better by n' by."

Because, you know, no one in the Howard administration ever once told us to stop. (Though they probably knew that it wouldn't do no good no how.) They never tried to coerce or threaten us with expulsion or other administrative sanction. Which was not the case with a lot of state dependent Southern black schools. For example, President Felton Clarke of Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, that year, to his shame, expelled all his student activists, nearly fifty students. Two of whom, Eddie C. Brown and his younger brother "Rap," ended up with us in NAG.

The administration knew full well who we were. But by the simple expedient of denying us recognition, they gave themselves "deniability." By disclaiming knowledge or responsibility, they did not have to move on us, and they never did. I can imagine our president, like Ellison's invisible man's grandfather, "yessing the white folk to death.” …

After spending the first two days registering, I set out to find NAG, which was not to be found.

"Nonviolent Action Group? NAG? Well, there is the NAACP. No? The Alphas, the Kappas, the French Club.... No? Sorry, I can't find any such organization on campus."

Ultimately I found someone Dion Diamond or John Moody, I think-who'd been at the anti-HUAC demonstration and could explain that NAG met every second Sunday off campus at the Newman House.

"But Howard's got an NAACP youth group, how come?" I asked.

"Course they do. But that's only because they never do anything, Jack. I don't think they even ever meet."

Which is how it was that on the second Sunday after my arrival I became a functioning member of SNCC, or at least its Washington, D.C., affiliate, the elusive NAG.

It is possible in hindsight to see some element of principle, strategy, and even political cunning in at least one of the university's actions that at the time had so infuriated us. Tell the truth an' shame the devil. But a host of other matters are not susceptible to any equally honorable explanation.

These came especially from middle and lower administration members and some faculty in the form of attitudes and policies that always angered us. I mean, they messed with our minds.

I'm talking an outmoded nineteenth-century missionary approach to "Negro education." We resented the patent condescension. According to which the educational mission was to "civilize young Negroes fresh from the cotton fields." It was to render us "cultured," i.e., polite and safe in word, thought, deed, and appearance so that ultimately superior white America might in its benevolence, one blessed day, accept "the Negro." Academically and culturally then, the imperative was to promulgate, uncritically, the curricula of American (read white) higher education and the attitudes and behavior of "the better class of white people." A few administrators would actually use such language to us without any evident embarrassment.

The assumption was that America had a "Negro problem," which was us. So that the onus was on us to improve ourselves. If only "the Negro" were less primitive and more responsible. If only they smelled less and glistened more, were more "cultured" and less crude, more industrious and responsible ad infinitum, then white America would gladly accept us. (Key word there, responsible. The white press used to brazenly issue orders thinly disguised as friendly advice to "responsible" Negro leaders. Responsible to whom or what?) Thus it was common on campus to hear Southern students harshly ordered to "learn to speak properly. Stop sounding so country." When in my sophomore year a NAG member (and my girlfriend) started to wear her hair natural, it precipitated hysteria among the dorm mothers. She was threatened with expulsion from the dorms and the school. Happily a young dean of women, Patricia Roberts, intervened and maturity prevailed. But this backwardness was wide spread and ingrained and greatly resented by every student I ever spoke to about it.

An aspect of this thinking carried over into the curriculum and instruction. Too many of the faculty bureaucrats who set curricula seemed content to accept the establishment textbook version of American reality. A dispensation in which we were either absent or present only as a lingering but peripheral problem in American life. The Negro as social liability. For these loyal Afro-Saxons, the only serious criticism of the mainstream was for its incomprehensible exclusion of deserving and highly evolved Negroes like themselves. Correct that single, inexplicable shortcoming by affording them their due social recognition and public acceptance, and America was perfect.

Of course, the implication of these attitudes that we students should strive for self-improvement while accepting respectfully all the values and practices of white America required rationalizing racist humiliation.

This was precisely the kind of psychic self-immolation that was totally unacceptable to our generation of students. Totally unacceptable, Jack.

We were young adults. The "foreign" students, Africans born elsewhere, tended to be even a little older. Many were mature men and women who had worked for years before being able to seek higher education. At the first general residents' meeting in the new Men's Hall dorm, I can remember standing next to a dignified "freshman" from Guyana who looked older than my father, and being gradually suffused with deep embarrassment and outrage at what we both were hearing.

The dorm director was extraordinarily condescending and not real smart. I listened in disbelief and growing humiliation as he spoke to us as though addressing children. The highlight of his address was a catalog of insulting "housekeeping" expectations apparently predicated on the assumption that most of us were encountering flush toilets and indoor plumbing for the first time. To the men from Africa and the Caribbean, as to us, he was their first official introduction to Howard, and for them by extension, to African-Americans. What on earth can they have thought of us?

At the foreign-student orientation I again received a shock. It was a large enough meeting. Mature and intelligent men and women from Africa and the Caribbean receiving their first orientation to the school, the city, and again the African community in America. And here was an African administrator of Howard University in effect planting the fear of "American Negroes" in our consciousness. We were not really encouraged to associate with black "Americans" cultural differences, they said and were warned not to venture freely into the surrounding community because of crime. It was "us and them" at its worst. Howard was in a typical black urban community, with all the problems associated with that, but whatever their intentions, the presentation from Howard representatives was heavy handed, crudely stereotypical, and a clear effort, I thought, to continue to divide Africans. I was furious. Had it come out of a white mouth, I'd have unhesitatingly dismissed it as racist. I resolved then and there to cultivate relationships with African brothers and sisters from outside the country and to try to pull them more and more into campus life and the social fabric of the African-American community. That became NAG's policy also.

But praise the Lord-evrah thang an' its opposite

...

… Ahm gonna lay down my sword and shield. Whether this was by inclination of the administration, by congressional dictate, the school's missionary origins, or by all three, I do not know. But I remember only two activities that were officially compulsory for all freshmen U.S. citizens: chapel on Sunday and the Reserve Officers' Training Corps.

I had no intention of entering the U.S. armed services, but in 1960 there was as yet no popular movement against the militarization of universities. So the only way I, as an individual, could resist was to get out of the marching, which I felt was a monkey show on campus, and also to raise the obvious contradictions in the military science classes.

We had a choice: the army or the air force. Since I had no intention of marching to and fro swinging my arms, I chose the air force, thinking there would be less parading about. But there was still too much.

So, the first day when we were lined up in our uniforms to march, Cadet Carmichael fainted. The second go-round I fainted again. The third time I fainted I was excused from the parade, permanently.

In the class discussions I would raise questions about the ethics of having training in the arts of massive destruction at a school allegedly educating us for the advancement of humanity. This was no mere debating ploy. I was seriously troubled by the clear contradictions, so I kept raising that and similar questions.

Our instructor was a captain, an African born in America. After a few classes he understood that (a) I was genuinely troubled by the contradictions and (b) I was not likely to shut up.

"Okay, Cadet,'' he said, "here's what's going to happen. Take the exams, and any grade you earn, I will award. And of course, you needn't worry too much about attending the classes." That was cool by me. I needed a grade to graduate so I read the book and took the exams.

Some students, more than a few, not only disagreed with my position but were passionate and vocal about it. These brothers felt that it was our patriotic duty to serve. Some were planning to enter the military professionally. The interesting thing is many of them were from the South. So it was easy. "Look, Jack, I'd love to be a patriot too. And just as soon as this country ends segregation, ends racial discrimination, stops the denial of legal and political rights to our people, I'll run to enlist. I be the first one, blood, I promise."

A distinguished historian on the faculty named Professor Rayford Logan, had written a famous dissenting history of Reconstruction called The Betrayal of the Negro. So naturally I hastened to take his course, in which we read his The Negro in American Life and Thought. Either in that book or in his lectures, we learned about a consignment of German prisoners of war being sent south to prison camps in Mississippi during World War II. Their guards were a detachment of black MPs. When the train crossed the Mason-Dixon Line, guess what? These armed African (American) soldiers, in the uniforms of their country, guarding "their" nation's enemies, were at mealtime ordered out of the air-conditioned white dining car to the Jim Crow eating cubicle at the rear of the train. The enemy prisoners, being "Aryan,'' were welcome to enjoy the comfort of the well-appointed white-supremacist dining car.

Truthfully, I had no idea I'd said anything aloud until Professor Logan stopped speaking. Professor Logan was very austere. No one ever interrupted him.

"Yes, did you say something?" he asked, staring at me.

"Sorry. I hadn't meant to," I muttered.

"Well, young man, what did you not mean to say?"

"I said, sir, that if it had been me, I would have blown that train to hell."

Professor Logan merely looked long at me and nodded. "Thank you," and he went on with his lecture. After that I couldn't wait to be accosted by the Southern patriots about ROTC.

….

It must be abundantly obvious by now exactly what an interesting combination Howard and the nation's capital was then. The extent to which the Howard experiences in that remarkable historical moment were various and multiple. All things to all men? Many things to many men? Certainly many different things to many different folk. Every dialectic in the African world was there to be found. And we sure managed to find evrah last one. So your education came at you in waves from myriad and unexpected directions other than the conventional. Just about everything about that place at that time was educational, even the classrooms. It all shaped us.

Excerpted from Stokely Carmichael and Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (Scribner, 2005).