The late Brazilian intellectual, artist, and activist Abdias do Nascimento argues that racial democracy is premised on an idea of racial mixing that not only valorizes whiteness, but is predicated on the dilution and disappearance of the African race -- on an annihilationist practice of “genocide.”

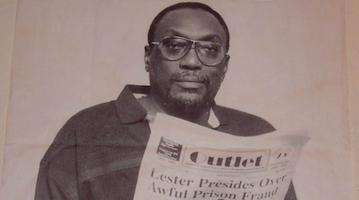

A recent issue of the Journal of Black Studies contains a special section dedicated to the life and work of Abdias do Nascimento. Nascimento was a Brazilian pan-Africanist and polymath who passed away in 2011 at the age of ninety-seven. Edited by anthropologist Keisha-Khan Y. Perry and Anani Dzidzienyo, the late Ghanaian scholar of Africa and Brazil, the journal issue provides an excellent introduction to a figure who, as the editors point out, is both a towering intellectual, cultural, and political figure in the Black world, and one who is surprisingly neglected and under-engaged.

The introduction, and the issue in its entirety, is a wonderful, often moving, tribute to Nascimento. Contributors to the issue write of his singular role in the development of Africana philosophy and Pan-African thought worldwide. They describe the impact of Nascimento’s experiences as a soldier in the Brazilian military in the early 1930s and his subsequent incarceration on his political and intellectual development. They discuss Nascimento’s philosophy of quiliombismo, a militant, collectivized practice of Black autonomy inspired by the seventeenth-century insurrectionist communities formed by Africans who escaped slavery on Brazil’s plantations. They survey Nascimento’s immense contribution to the arts and the representation of Africa in Afro-Brazilian culture via painting, theatre, film, and sculpture, from his time working with the Teatro Experimental do Negro to Theatre in the 1940s and 1950s to his time in exile in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. They also write of Nascimento’s contribution to changing the national discourse in Brazil around race relations, organized resistance, and state policy.

One of Nascimento’s most important political interventions arrives through his dismantling of the benign mythology of Brazil’s “racial democracy.” Nascimento argues that racial democracy is premised on an idea of racial mixing that not only valorizes whiteness, but is predicated on the dilution and disappearance of the African race -- on an annihilationist practice of “genocide.” This genocide occurs through sexual violence against Black women, the encouragement of white immigration, and the disportionate use of the law to contain, surveil, and punish Brazil’s African population. Today, the genocide of Brazil’s Afro-descended populations occurs through racist state violence in the form police murders and dispossession. In Rio de Janeiro, police admitted to killing 606 people in the first four months of 2020. Close to six people a day were murdered by police in April of the same year. In May of this year, police killed twenty-eight people during a heavily-militarized attack on a Rio de Janeiro favela. In the past decade, of the 9000 people killed by police, three quarters were Black men.

Nascimento’s first statements on genocide in the Brazilian context were made in Africa: at seminars in Dakar, Senegal and Ife-Ife, Nigeria, in 1976 and 1977, respectively. They first appeared in print in English in 1979 in the collection Mixture or Massacre: Essays in the Genocide of a Black People. Mixture or Massacre was published by Nascimento’s Afrodiaspora imprint, started while he was teaching with the Puerto Rican Studies and Research Center, State University of New York at Buffalo. A decade later the Trinidad pan-Africanist Tony Martin reprinted Mixture or Massacre through The Majority Press. In honor of Nascimento, and to mark the November 20th, Black Consciousness Day in Brazil, we reprint a short excerpt from the essay “Genocide: The Social Lynching of Africans and their descendants in Brazil” below.

Genocide: The Social Lynching of Africans and their descendants in Brazil

Abdias do Nascimento

Brazil as a nation proclaims herself the only racial democracy in the world, and much of the world views and accepts her as such. But an examination of the historical development of my country reveals the true nature of her social, cultural, political and economic anatomy: it is essentially racist and vitally threatening to Black people.

Throughout the era of slavery from 1530 to 1888, Brazil carried out a policy of systematic liquidation of the African. From the legal abolition of slavery in 1888 to the present, this scheme has been continued by means of various well-defined mechanisms of oppression and extermination, leaving white supremacy unthreatened in Brazil.

During the era of Western colonial expansion, the African people were considered non-human and bestial. The tradition of European racism which uniquely informed the system of enslavement of Africans by Aryans differentiated it from all other forms of slavery known to human history. Slaves were forced to live the filth, misery and degradation of their "scientifically determined" social status. This meant medical and hygienic neglect, malnutrition and subjection to physical torture and sexual abuse. These tribulations led to the mental, emotional and cultural deprivation of the Black people with which we are all, I think, familiar.

After "abolition," the masters, especially owners of coffee plantations in the Southern states, refused to employ "freed" Black people as workers and gave preference instead to Aryan immigrants from Europe. They denied former slaves the most basic element of subsistence, then accused them of laziness and indolence or of having no interest in leading productive lives. They ignored the basic fact that it was they themselves who had turned the African slave into "little more than a brute and little less than a child" by their infamous exploitation of him and of his family. Then they turned the result of this process of dehumanization into an "argument" against any possibility of his becoming a free man.

During and since slave times, the most effective tool of physical and spiritual genocide of Black people has been the manipulative mystique of whitening the Brazilian population.

The testimonies to the predominantly and often explicitly racist orientation of Brazilian immigration policies are many and varied. They attest to a prevalent attitude that the Brazilian population was ugly and genetically inferior because of the presence of African blood, and that it needed to "... fortify itself through joining with the higher value of the European race." ...

This attitude was endorsed by supposedly scientific and sociological theory, which provided vital intellectual support for the white supremacist ploys. In the words of leading intellectual Silvio Romero: "My argument is that future victory in the life struggle among us will belong to the white race."... Writer José Verissimo also remarked:

As ethnographers assure us, and as can be confirmed at first glance, race mixture is facilitating the prevalence of the superior race here. Sooner or later it will eliminate the black race. Here this obviously already is happening….

Religious endorsement of these concepts was also obtained: even the Catholic church held that the Black people suffered “infected blood.”...

The aggressively racist nature of the official policies of immigration is not difficult to discern: as late as the administration of Getulio Vargas, on 18 September 1945, by Law Decree 7967, the government regulated the entry of irrimigrants according to

...the necessity to preserve and develop in the ethnic composition of the population the more desirable characteristics of its European ancestry. ...

The support of the intellectual and religious sectors allowed the governing strata to exercise these policies over almost all the aspects of Brazilian society. Various strategies of domination developed in the cultural composition of the society, one of them being religious repression. Aryan western cultural imperialism masks itself in a movement of apparent exchange of influences labelled among conventional scholars as religious syncretism. This expression, however, ignores the fact that such a term is legitimate only if "exchange" occurs in an atmosphere of living spontaneity. In the case of Afro- Brazilian culture, on the contrary, we are dealing with the more or less violent imposition or superimposition of white Western cultural norms and values in a systematic attempt to undermine the African spiritual and philosophical modes. Such a process can only be described as forced syncretization.

Another deadly tool in this scheme of immobilizing and fossilizing the vital dynamic elements of African culture can be found in its marginalization as simple folklore: a subtle form of ethnocide. All of these processes take place in an aura of subterfuge and mystification in order to mask and dilute their significance or make them seem ostensibly superficial. But despite such attempts at deceit, the fact remains that the concepts of white Western culture reign in this supposedly ecumenical culture in a country of Blacks, marginalizing and undervaluing our heritage of Africa in the process. For this white- identified culture, the "folkloric man" is the natural man, destitute of history, projects and problems. He has only a profound alienation from his African identity. Since raw material is non-entity waiting to take form, for this conventional culture "folklore" is the raw material that the white man manipulates, manufactures and profits from.

On the whole, in this pretentious concept of "racial democracy," there lies deliberately buried the true face of Brazilian society: only one of the racial elements has any rights or power — whites. They control the means of dissemination of information, educational curriculum and institutions, conceptual definitions, aesthetic norms, and all other forms of social/cultural values. This control accounts for the widespread and rather innocent belief of the Brazilian people in "racial democracy" itself.

A bibliography of the work of Abdias do Nascimento can be found here, at the Instituto de Pesquisas e Estudos Afro Brasileiros. Keisha-Khan Y. Perry’s and Anani Dzidzienyo’s “Homenagem: Remembering the Life and Work of Abdias Nascimento” in their special issue of the Journal of Black Studies is unfortunately behind a paywall.