Legendary Pan-Africanist and Marxist journalist, Samori Marksman provides a powerful archive of the scale and scope of nefarious US actions in the Caribbean region.

The August-September 1980 edition of the investigative magazine Covert Action Information Bulletin was dedicated to “Destabilization in the Caribbean” – a theme as urgent now as it was then. In the early 1980s, the Caribbean states suffered under both covert and overt actions by the US. Today, we are currently watching the real-time meddling – perhaps bungling is a better word – of the US in the internal affairs of Haiti. We are also witnessing the slavish attempts by Guyana and Barbados to position themselves as the faces of US foreign policy in the region, and the ongoing US economic and political sanctions against Cuba and Venezuela.

The editors of Covert Action recognized the historical importance of the Caribbean to US foreign policy and American corporate strategy. They also saw the region as “one of the most crucial areas in the struggle between reaction and progress” as Leftist governments fought to chart their own paths towards political and economic self-determination, unhindered by the imperial monstrosity that Cuban nationalist José Martí famously called “the Colossus of the North.”

It was the largest issue that Covert Action had ever published. It contained an extended investigation of US attempts to undermine democratic socialism in Michael Manley’s Jamaica; a reprint of a speech by Maurice Bishop to the people of Grenada—given just hours after he survived an assassinaton attempt; and an overview of the transition from political repression to outright terrorism in Forbes Burnham’s Guyana, a transition punctuated by the murder of Walter Rodney in Georgetown on June 13, 1980.

Also included in the issue is a phenomenal overview of US military interventions, occupations, and destabilization efforts in the Caribbean, written by the legendary Caribbean Pan-Africanist Marxist journalist, historian, political activist, teacher, and WBAI program director Samori Marksman (October 27, 1947 – March 23, 1999). Marksman outlines this history from the era of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine to the 1980s (skipping, unfortunately, the series of U.S. occupations of Cuba, Haiti, Panama, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic). He provides us with a powerful document archiving both the scale and scope of US policy in the region. Most importantly, Marksman reminds his North American readers that the Caribbean is not merely a sun-drenched beach providing a background to a rum-soaked vacation. It is, instead, a real place, with real people, who are struggling for control over their lives, and fighting to assert their dignity. We reprint Samori Marksman’s essay below.

Destabilization in the Caribbean: An Overview

Samori Marksman

Rum and reggae-rhythms, calypso and coke, beaches and bongo-drums, hot-sun and hedonism.... By now the average North American is already familiar with these standard depictions of “the Caribbean reality.” Unfortunately, however, life for the overwhelming majority of Caribbean people is far from pleasureful. These “nativistic,” tropical-paradise images are more figments of a tourist imagination than true reflections of the day-to-day rigors of human survival in these poor, undeveloped Third World societies. Had this misperception also been pervasive among U.S. government officials, then those Caribbean patriots who are merely seeking to rearrange their societies to provide basic human needs for their people, would not be faced with the degree of U.S.-engineered intrigue and sabotage against their respective efforts that we are witnessing today.

The real “Caribbean realities” are very much on the minds of those who formulate U.S. policy for the region. Recent political changes in Grenada and Nicaragua, the social leanings of the People’s National Party of Jamaica, the potential for radical social change in El Salvador and Guyana, and the success of the Cuban revolution are all studied and perceived in Washington as “threats to the national security of the United States of America.” And U.S. reaction to these changes has been swift and vicious—sometimes naked and ugly—as in Guyana, beginning with the CIA’s toppling of the [Cheddi] Jagan government, the installation of the Burnham regime, up to the recent assassination of Dr. Walter Rodney; in Cuba, with the “permanent plot” of assassination, economic strangulation, and political destabilization against the government; and recently, in Grenada, with the attempted assassination of that country’s entire leadership.

At times U.S. reaction has been much less overt, more sinister, as in the CIA’s protracted campaign of destabilization against the government of Jamaica’s Michael Manley; the application of the strategy of “new-diplomacy,” that is, deploying a younger, “more hip,” more physically attractive corps of diplomats to the region; offering liberal sums of money and special training programs to trade union leaders from the region; or acts of economic destabilization via U.S.-based or U.S.-controlled transnational lending institutions, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development, the International Monetary Fund, the Caribbean Development Bank and so on.

Why Such Hysteria in Washington?

The reaction of the U.S. and other North Atlantic governments to progressive changes in the Caribbean, changes which take some of these states onto a path of non-capitalist development, could, perhaps, be explained on two levels: 1) The “natural” systemic reaction, that is, the reaction of the capitalist bloc to what it perceives as contradictory tendencies within its “own” historic hemisphere-of-influence; and 2) The strategic reaction to what the North Atlantic bloc perceives as “an intrusion” by the Soviet Union into their traditional domain.

In neither case are those factors pertaining to the human, social and historic desires and interests of the Caribbean people themselves taken into account.

And what are these basic desires and interests?

Foremost is the desire to assume full responsibility for determining their own destiny. To be able to feed, clothe, shelter and develop themselves. And to work alongside all decent human beings to bring about a more humane global order.

The Caribbean islands are not economic monstrosities poised to devour the capitalist metropolis. They do not have multi-billion dollar trade surpluses with Western Europe and North America. They do not (with the exception of Trinidad) possess any known, large quantities of oil or natural gas. Nor do they own or control transnational lending institutions and industrial conglomerates.

These are basically poor, undeveloped, agricultural economies which do not perceive the primary contradiction in the world today as that of “East vs. West'' but rather as one between the advanced North Atlantic capitalist countries of the so-called “First World" on the one hand, and those of the underdeveloped “Third World” on the other. In other words, they perceive it as a “North vs South'' contradiction.

In the smaller islands which make up the Eastern Caribbean Common Market (Antigua, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St. Lucia, St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, and St. Vincent), the magnitude of their poverty is staggering— and is exacerbated further by their almost total dependency upon foreign financial support. Local consumption (in many cases) absorbs in excess of 100% of the Gross Domestic Product. Which means that virtually all investments are financed by external sources. Even the state (public) sectors of these economies rely upon external sources for no less than 85% of their investment capital. Many of these primitive economic circumstances are not dissimilar to those existing in the “more developed” Caribbean states of Jamaica, Guyana and Barbados. The economic conditions and their negative social spin-offs are, for the most part, colonial inheritances—handed down by the capitalist European states and later (after independence) aggravated by the avaricious economic and political policies of the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and France toward the region.

If one is to believe the policy utterances coming from Washington these days pertaining to the “new communist threat” in the Caribbean and, therefore, the need for the U.S. government to “become involved” in countering this threat, one might be misled into thinking that active U.S. intervention in this area is a new development.

U.S. interventionist policies date back to the eighteenth century when George Washington, while in the process of trading Black slaves from the North American mainland — in exchange for rum in Barbados—attempted to undermine British authority over the island. It evolved with US military/merchant fleets and traders competing fiercely with the Spaniards, Dutch, French and English for monopoly of the slave traffic and control of markets and contested territories such as Haiti and Cuba.

In 1823, with the introduction of the hegemonistic Monroe Doctrine, U.S. authorities now had “legitimate” grounds to lay claim and domination over the Americas, including the Caribbean.

U.S. de facto colonization of Cuba after the so-called “Spanish-American War” and the subsequent seizure and colonization of Guantanamo and Puerto Rico is now common knowledge.

It established a military base at Chaguaramas on the island of Trinidad. It overturned a popular regime and installed a right-wing dictatorship in Guatemala in 1954. It invaded Cuba in 1961, the Dominican Republic in 1965, sent military ships to Trinidad and Tobago in 1970 to quell a popular uprising, and U.S.-based corporations set up military installations in Antigua and Barbados in the mid-1070s, and used their facilities in Antigua to transship military hardware to the fascist regime in South Africa. And, more recently, direct U.S. military assistance to Barbados and other islands have become an integral part of its new strategy for the region.

“Nothing to Lose”

The prevalence of unemployment rates over 50% among adult workers in most of the territories (over 75% among the youth), primitive health facilities (where they exist), high illiteracy rates, non-existent Social Security programs, cave-age developmental “strategies,” and regimes which see their role as that of state catchment for expatriate financial interests, only serve as political mobilizing factors — around which the workers, youth, peasants, declasses, and revolutionary intelligentsia can— and are rallying. And in those territories where these forces have rallied and organized to redress these conditions, the stratal and parastatal gendarme machinery, trained and equipped by U.S. Canadian, British and French police and intelligence agencies, unleash their brutal repression against the people—as was seen in Grenada under Gairy, in Nicaragua, Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago and elsewhere.

The tide of radical social change currently surging through the Caribbean basin is, unfortunately, seen by U.S. authorities through eyes blinded by neo-Kiplingesque paternalism and afflicted by Soviet/Cuban phobia. One example is that after the social and economic devastation left behind in Grenada from years of being in the eye of what the Grenadians knowingly call “Hurricane Gairy,”a devastation which the courageous leadership of the New Jewel Movement is attempting to correct, U.S. authorities have only been able to come forward with paternalistic counsel: “Don't establish relations with Cuba ... or else!" “Don’t deal with East European and Arab countries!” “Don't go to the Non-Aligned Summit Conference!" etc.; and pocket change: a few $5,000.00 "development" projects. Yet the changes in Grenada are seen as “Soviet and Cuban expansionism,” the fulfillment of the Kremlin’s manifest destiny.

Regrettably, this view is shared by many leftists and academicians in North America. Some irresponsibly and piously sling “analytical" terms and descriptions of the emerging progressive Caribbean states—“Bonapartist," “surrogate states," etc.—which only serve to splinter, confuse and weaken international support for these popular movements and strengthen reaction. Others—betraying a sense of eternal faith in imperialism's “good side" and who subscribe to the theory of intra-bourgeois-party ambidexterity—sit and wait, lethargically, for “progressive elements” within the dominant, explicitly pro-imperialist parties in the U.S. Canada, U.K., and France to rise and implement new policies.

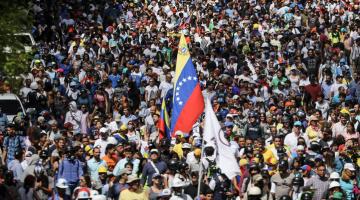

The mortal reality in the Caribbean today is that a profound, dynamic, mass-based revolution is taking place throughout the region. U.S.-led counterrevolution in the area is equally widespread. “Stop Jamaica before it’s too late,” “Don’t let Grenada provide an example," “Stifle Cuba," are strategies all in full operation. North Americans, especially U.S. citizens who profess a sense of international goodwill and concern for humanity, must view it as their duty and responsibility to call a halt to their government's and some private institutions’ interference in the internal affairs of Caribbean countries whose people are crying out: "We are more than beaches . . . we are countries–with real people.”

Samori Marksman, “Destabilization in the Caribbean: An Overview,” Covert Action Information Bulletin 10 (August-September 1980)