In the past year or two, the proposition of defunding or abolishing police and prisons has travelled from incarcerated-activist networks into mainstream conversations.

“Mariame Kaba, a New York City-based activist and organizer, is at the center of an effort to “build up another world.”

The murder of George Floyd last spring provoked an unprecedented outpouring of protests, and a rare national reckoning with both racism and police violence. Public officials across the country pledged police reform. On April 20th, Derek Chauvin, the officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes, was found guilty of murder. It is rare for police to be prosecuted, let alone punished. I remember my incredulous reaction, in 1992, when my mother called to tell me that the four police officers who beat Rodney King, in Los Angeles, were found not guilty. I remember, in the summer of 2013, being at a Chicago restaurant, having dinner with my wife, and feeling the numbing shock of seeing in real time, on television, George Zimmerman acquitted for the murder of Trayvon Martin. We left the restaurant to join a protest downtown, crossing the street to catch the train. When I walked through the turnstile, a Black woman wearing the uniform of the Chicago Transit Authority looked at me with tears in her eyes, and mouthed, “They let him get away with it.” For most ordinary African-Americans who have watched helplessly, for years, as police act with violent impunity in their communities, the conviction of Chauvin feels like justice long delayed. For Floyd’s family, the verdict came as a relief. Philonise Floyd said that the conviction “makes us happier knowing that his life, it mattered, and he didn’t die in vain.”

In a certain sense, the trial of Chauvin has been viewed as a piece of a national reform strategy. There is a hope that his conviction will serve as evidence that police do not operate above the law and that they can be subjected to its punishments. But if it takes tens of millions of people marching, and an extraordinary recording capturing Chauvin’s cool torpor as Floyd’s life left his body, to secure some measure of legal accountability for the police, then what does this conviction mean for the transformation of American policing? In effect, Chauvin had to be convicted for it to remain even remotely credible that, in the United States, the law protects the rights of African-Americans. Pursuing such an outcome allowed Chauvin’s employers and supervisors to disavow him, describing him as a rogue cop who had abandoned his training. “Policing is a noble profession,” the prosecutor Steven Schleicher said at the trial. “Make no mistake, this is not a prosecution of the police—it is a prosecution of the defendant. And there’s nothing worse for good police than bad police.””

“For most ordinary African-Americans the conviction of Chauvin feels like justice long delayed.”

Days into the protracted spectacle of the Chauvin trial, the police killing of an unarmed twenty-year-old Black man, Daunte Wright, ten miles north of Minneapolis, in the suburb of Brooklyn Center, sparked fresh protests. The details of that latest outrage bore all the markings of the sanguinary and absurd cycle of racist police violence. Consider that police stopped Wright’s car because of some minor technicality often used a pretext for racial profiling, that they threatened him with arrest because of an existing warrant, and that, in the most tragic turn of events, the officer who killed Wright claimed to confuse her Taser with her gun. Within hours of his murder, the chief of police and the officer who pulled the trigger, Kim Potter, had resigned their jobs, and Potter was subsequently arrested for second-degree manslaughter. The quick resignation and arrest are other indications that things are not quite the same regarding the police, but nothing that led to the confrontation and the ultimately death of Wright has been undone.

Indeed, as the high-stakes trial of Chauvin was unfolding, the news was roiled by the release of body-camera footage showing a Black soldier being pepper-sprayed during a routine traffic stop in Virginia, followed by the release of body-camera footage documenting the police shooting, in Chicago, of thirteen-year-old Adam Toledo, his empty hands in the air. Chicago officials initially claimed that Toledo had an “armed confrontation” with the officer who shot him. Misleading comments from Mayor Lori Lightfoot and others revived memories of the murder of seventeen-year-old Laquan McDonald, seven years earlier. McDonald was shot sixteen times by a Chicago cop, Jason Van Dyke, who claimed that the teen-ager attacked him with a knife. Subsequent release of dashboard-camera footage showed McDonald walking away from the police as Van Dyke unleashed a fusillade of bullets in his direction. The revelations surrounding McDonald’s murder exposed a coverup that stretched high into Chicago’s political leadership, effectively ending the then mayor Rahm Emanuel’s political career there. The killing of McDonald was also supposed to usher in a new period of police reform in a city long dogged by scandals and crises of police racism, corruption, and brutality. Jason Van Dyke was also convicted of murder, but the controversy surrounding the death of Adam Toledo shows that the Chicago Police Department remains far from reformed.

Minutes before the verdict in the Chauvin trial was revealed, a white police officer in Columbus, Ohio, shot a Black sixteen-year-old, Ma’Khia Bryant, four times in the chest, killing her. Bryant was wielding a knife and threatening to stab another girl when she was shot, but the officer’s default to shooting and Bryant’s resulting death quickly dashed any hopes that the guilty verdict in Minneapolis indicated a turning point in American policing. Since then, new cases involving police shootings of unarmed Black men have surfaced in North Carolina and Virginia.

“Ma’Khia Bryant’s resulting death quickly dashed any hopes that the guilty verdict in Minneapolis indicated a turning point in American policing.”

The continuation of police abuse has reaffirmed the calls of some activists for an end to policing as we know it; for others, it has confirmed that the institution of policing should be abolished completely. In the past year or two, the propositions of defunding or abolishing police and prisons has travelled from incarcerated-activist networks and academic conferences and scholarship into mainstream conversations. Of course, this doesn’t mean that these politics have become mainstream, but the persistence of police violence disproportionately harming Black communities has pushed far more people to contemplate radical proposals for dealing with issues of harm and safety.

One Black woman who has been at the center of these conversations is Mariame Kaba, an educator and organizer who is based in New York City. Kaba fund-raised for large-scale mutual-aid operations as the impact of covid-19 began to set in and the lack of public provisions threatened hunger, homelessness, and illness for untold numbers. She is also known for helping to organize a successful campaign to award reparations to Black men who survived torture orchestrated by the former Chicago police commander Jon Burge. Those reparations include a five-and-a-half-million-dollar compensation fund for the victims and their families, waived tuition at the City Colleges of Chicago, a mandatory curriculum for Chicago public schools about the police torture, and a public memorial. It was an unprecedented campaign and outcome, which mirrored the professed values of the growing abolitionist movement: repair and restoration. Kaba and her fellow-activists were less interested in prosecuting the offending police officers than in developing initiatives that could repair the harms done by the Chicago Police Department.

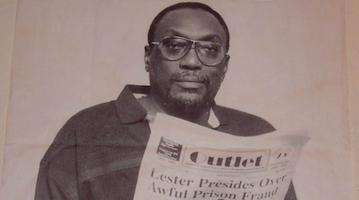

Many were introduced to Kaba and her work through her blog, Prison Culture, which she began, in 2010, as a way to talk about her organizing projects and to educate and engage with a small public about the consequences of prevailing law-and-order politics in the United States. Kaba writes in Prison Culture about the culture of punishment that has functioned as a guiding principle in American jurisprudence. She also shares movement reports, articles published elsewhere, poems from other writers, and lots of visual art. When I spoke to Kaba recently, she told me, “I am not interested in writing. I am an organizer who writes.” But, as an organizer, she writes quite a bit, and, in February, she published a book, “We Do This ’Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice,” an eclectic collection of articles, interviews, speeches, short pieces co-written with some of Kaba’s political collaborators, and more, edited by the sociologist Tamara K. Nopper.

The book, which débuted on the Times best-seller list, offers an entry point into the world of abolitionist politics, beginning with an essay titled “So You’re Thinking about Becoming an Abolitionist.” It contains several basic but profound observations: “Increasing rates of incarceration have a minimal impact on crime rates. Moreover, crime and harm are not synonymous. All that is criminalized isn’t harmful, and all harm isn’t necessarily criminalized.” If there is a mismatch between punishment and crime, and crime and harm, then what is the intent of the criminal-justice system and the police it employs? Kaba refers to the “criminal punishment system” to emphasize that justice in the United States means a promise of retribution much more than an effort to understand why an infraction has occurred. She writes, “If we want to reduce (or end) sexual and gendered violence, putting a few perpetrators in prison does little to stop the many other perpetrators. It does nothing to change a culture that makes this harm imaginable, to hold the individual perpetrator accountable, to support their transformation, or to meet the needs of the survivors.” When we spoke, Kaba told me, “I am looking to abolish what I consider to be death-making institutions, which are policing, imprisonment, sentencing, and surveillance. And what I want is to basically build up another world that is rooted in collective wellness, safety, and investment in the things that would actually bring those things about.”

“I am looking to abolish what I consider to be death-making institutions.”

Kaba is the daughter of West African immigrants who came to the United States in the sixties, her mother from Côte d’Ivoire and her father from Guinea. Her father completed graduate studies, in economics, at Columbia before accepting a job at the United Nations. Kaba, born in 1971, came of age in the racial tumult of nineteen-eighties New York City. She recalled “going to school on the subway, and all the sudden seeing houseless people in the subway. . . . It had a lot to do with deinstitutionalization, as well as the crack epidemic, as well as the aids epidemic, as well as all these things piling onto each other at the same time.”

In our conversation and in her book, she made note of the police killing of Michael Stewart as formative to her own political awakening. On September 15, 1983, Stewart, a twenty-five-year-old African-American artist, was arrested for graffitiing the subway. Transit police beat and hog-tied him; he never regained consciousness. Nearly two years later, an all-white jury acquitted six police officers accused of murdering Stewart. On October 29, 1984, the sixty-seven-year-old Eleanor Bumpurs was shot and killed by police who were assisting in her eviction from public housing in the Bronx. Bumpurs suffered from mental illness, claiming that Ronald Reagan had come through the walls of her home, and she had barricaded herself inside her apartment. As police broke through the front door, Bumpers, wielding a knife, was shot twice, in the hand and the chest. The cop who shot Bumpurs was eventually acquitted of manslaughter charges. Both cases received national attention and inspired grassroots organizing and protest. Kaba notes that, while she was drawn into action to protest the killing of Stewart, she was not compelled in the same way by the activism surrounding the killing of Bumpurs. She writes, “I remember very clearly that she was killed. I remember that people were organizing against her killing. I don’t remember organizing against it, because I thought very much that the killing of Black men was the main thing we were fighting to end. I didn’t see myself so much as a woman or a girl. In terms of my own identity, my gender didn’t figure in the way that my race did.”

This had changed by the time Kaba left college and returned to New York City to work with survivors of domestic violence. She was befuddled that many of the women she was working with did not want to call the police on their partners. Kaba said, “Then I started asking people questions like, ‘Why don’t you want to go to the police?’ And people would look at me, like, ‘What are you talking about? Why wouldn’t I go to the cops? Do you not see who I am? The cops don’t keep me safe.’ And so I slowly came to consciousness.” In her book, Kaba writes, “What happens when you define policing as actually an entire system of harassment, violence, and surveillance that keeps oppressive gender and racial hierarchies in place? When that’s your definition of policing, then your whole frame shifts. And it also forces you to stop talking about it as though it’s an issue of individuals, forces you to focus on the systemic structural issues to be addressed in order for this to happen.”

“What happens when you define policing as actually an entire system of harassment, violence, and surveillance that keeps oppressive gender and racial hierarchies in place?”

There is no definitive beginning point for prison-abolition politics, but it is clearly connected to a turn, beginning in the sixties, in American imprisonment, in which it went from a method, in part, of rehabilitation to one of control or punishment. During the civil-rights movement, police were the shock troops for the massive resistance of the white political establishment in the American South. By the mid-sixties, policing and the criminal-justice system were being retrofitted as a response to a growing insurgency in Black urban communities. By the seventies, they were being used to contain and control both Black radicals and Black prisoners. The scholar and activist Angela Y. Davis may be the best-known prison abolitionist in the United States today. But, in 1972, she was facing charges of kidnapping, murder, and conspiracy, after guns registered to her were used by the seventeen-year-old Jonathan Jackson, in a botched attempt to free his brother, the Black radical George Jackson, from Soledad prison.

Davis had become a leader of George Jackson’s defense committee and had developed a close relationship with him. As a result of their collaboration, and of Davis’s experience of spending sixteen months in jail before her acquittal, she devoted her political energies to prisoners’ rights and eventually to prison abolition. In an interview that she gave while awaiting the outcome of her trial, Davis said, “We simply took it upon ourselves at first to defend George Jackson, John Clutchette, and Fleeta Drumgo”—the radicals known as the Soledad Brothers. “But we later realized that the question was much broader than that. It wasn’t simply a matter of three individuals who were being subject to the repressive forces of the penal system. It was the system itself that had to be attacked. It was the system itself that had to be abolished.”

In 1995, the radical theorist Mike Davis wrote a cover story for The Nation describing a new “prison-industrial complex” being established in California, with no pretense that the exponential growth of prisons was tied to the rise and fall of crime. Indeed, according to the scholar and activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore, in her pathbreaking book “Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California,” even though the crime rate peaked in 1980, between 1984 and the early two-thousands, California “completed twenty-three major new prisons,” at a cost of two hundred and eighty to three hundred and fifty million dollars each. By contrast, the state had built only twelve prisons between 1852 and 1964. Bodies were necessary to justify the rapid growth of the prison sector, and the Crime Bill of 1994, along with California’s three-strikes legislation, passed that same year, provided them. Gilmore writes that “the California state prison population grew nearly 500 percent between 1982 and 2000.” The three-strikes law, which mandated twenty-five-years-to-life sentences for a third felony, had an especially severe effect on Black and Latinx communities. Mike Davis reported that, during the first six months of prosecutions under the new law, “African-Americans made up fifty-seven percent of the ‘three strikes’ filings in L.A. County,” even though they made up only ten per cent of the state population. This was seventeen times higher than the rate at which whites were being charged under the new law, even though white men were responsible for “at least sixty percent of all the rape, robberies, and assaults in the state.”

“The California state prison population grew nearly 500 percent between 1982 and 2000.”

The three-strikes law was an accelerant to what would come to be called “mass incarceration,” but it was also the makings of a new movement against prisons and against the means and methods by which they became populated—namely, policing. In 1997, in Berkeley, Davis, Gilmore, and others formed the organizing group Critical Resistance, which brought together activists, the formerly incarcerated, and academics to “build an international movement to end the prison industrial complex by challenging the belief that caging and controlling people make us safe.” Ten years later, Gilmore published “Golden Gulag,” which she describes as the culmination of research projects undertaken with Black mothers of incarcerated persons in California state prisons. She wrote, “What we learned twice over was this: the laws had written into the penal code breathtakingly cruel twists in the meaning and practice of justice.” This produced new questions, extending far beyond the passage of new laws. The mothers, along with Gilmore, asked, “Why prisons? Why now? Why for so many people—especially people of color? And why were they located so far from prisoner’s homes?” In this sense, although academics have been important to formulating the movement’s arguments, the journey toward abolition is not an academic or intellectual exercise. Instead, it has been gestated within the communities deeply scarred by the disappearing of sons and daughters by the state.

By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, the cumulative, devastating effects of twenty years of increasing policing and incarceration—inaugurated by Reagan but abetted by the policies of the Clinton Administration—came into greater focus, as new conversations opened up about structural inequality in the United States. Michelle Alexander’s book “The New Jim Crow,” published in 2010, offered a breakthrough analysis of continued Black inequality as a product of years of policing and imprisonment in Black communities. Kaba identifies the failure to stop the execution of the Georgia death-row inmate Troy Davis, in 2011, as catalyzing the emergence of an abolitionist consciousness among what Elizabeth Alexander has described as the “Trayvon Generation.” Five months after Davis’s execution, Trayvon Martin was killed by George Zimmerman. Kaba noted that “the call, when Trayvon Martin was killed, was to arrest and to prosecute and to convict Zimmerman.” In 2014, after Michael Brown was killed, “the push was to indict Darren Wilson, and for body cameras.” Zimmerman was acquitted, and a grand jury failed to bring charges against Wilson. Kaba said, “And, because so many of these young folks were actually mobilized in the organizing, they could see the futility of the demands that they were making and the limits of those demands, and wanted and were ready to hear something new.”

That generation’s maturation in the world of police reform became apparent last summer, when many young activists and organizers began to embrace a demand that funding for police departments be redistributed to other public agencies and institutions. The demand originated in Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed, and where the city council briefly committed to defunding the police department. But, Kaba said, it’s important to note that local Black radical organizations—Black Visions Collective, Reclaim the Block, and MPD150—had been campaigning for years to divest from the police department and invest in community groups, battling the police over the city’s budget. She explained, “You’ve already got folks on the ground over there that have had two cycles of budget fights around defunding the police based on divestment. So the part of this people don’t understand is the continuity of these ideas. They don’t just come out of nowhere. People aren’t just yelling stuff randomly. It got picked up nationally because people were, like, ‘This makes sense.’ ”

“Local Black radical organizations had been campaigning for years to divest from the police department and invest in community groups.”

Although the demand to defund the police may have had its specific origins in Minneapolis, Kaba understands that the growing curiosity about abolitionist politics is rooted in something much broader. She said, “People are frustrated by the way that the welfare state has completely been defunded. People don’t have what they need to survive. And yet the military and prisons keep getting more and more and more.” Contrary to the beliefs of their critics, abolitionists are not impervious to the realities of crime and violence. But they have a fundamental understanding that crime is a manifestation of social deprivation and the reverberating effects of racial discrimination, which locks poor and working-class communities of color out of schooling, meaningful jobs, and other means to keep up with the ever-escalating costs of life in the United States. These problems are not solved by armed agents of the state or by prisons, which sow the seeds of more poverty and alienation, while absorbing billions of dollars that might otherwise be spent on public welfare. The police and prisons aren’t solving these problems: they are a part of the problem.

At its core, abolitionist politics are inspired by the necessity for what Martin Luther King, Jr., described as the “radical reconstruction” of the entirety of U.S. society. They intend to promote systemic thinking instead of our society’s obsession with “personal responsibility.” Derek Chauvin’s conviction was premised on the idea that he was personally responsible for George Floyd’s murder. The emphasis on his accountability distracts from a system of policing that administered his continued employment, even though eighteen complaints had been lodged against him during his nineteen-year career. Moreover, Chauvin was a field-training officer, who had trained two of the other officers who will face trial for participating in Floyd’s murder. Chauvin may be held to account for the killing, but neither the Minneapolis Police Department nor the elected officials charged with overseeing the M.P.D. will be held to account for allowing someone like Chauvin to be on the streets, let alone responsible for training others.

To approach harm systemically is to imagine that, if people’s most critical needs were met, the tensions that arise from deprivation and poverty could be mitigated. And when harm still occurs, because human beings have the propensity to hurt one another, nonlethal responses could attend to it—and also to the reasons for it. To be sure, these are lofty aspirations, but they are no more unrealistic than believing that another study, exposé, commission, firing, or police trial is capable of meeting the desire for change that, last summer, compelled tens of millions of ordinary people to pour into the streets. Indeed, the trial of Derek Chauvin could not even conclude before a Black man was killed at a traffic stop.

Our current criminal-justice system is rooted in the assumption that millions of people require policing, surveillance, containment, prison. It is a dark view of humanity. By contrast, Kaba and others in this emergent movement fervently believe in the capacity of people to change in changed conditions. That is the optimism at the heart of the abolitionist project. As Kaba insists in her book, “The reason I’m struggling through all of this is because I’m a deeply, profoundly hopeful person. Because I know that human beings, with all of our foibles and all the things that are failing, have the capacity to do amazingly beautiful things, too. That gives me the hope to feel like we will, when necessary, do what we need to do.” Abolition is not an all-or-nothing proposition. Even the guiding lights of the movement are embedded in campaigns for short-term reforms that make a difference in daily life. For Kaba, that has meant raising funds for mutual aid during the pandemic and campaigning for reparations in Chicago. For Gilmore, it has meant working with incarcerated people and their families to challenge the building of prisons across California. For Angela Davis, it has meant lending her voice to movements for civil and human rights, from Ferguson to Palestine. The point is to work in solidarity with others toward the world as they wish for it to be. “Hope is a discipline,” Kaba writes. “We must practice it daily.”

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor is a contributing writer at The New Yorker. She is an assistant professor of African American Studies at Princeton University and the author of several books, including “Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership,” which was a 2020 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for history.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com