A Freedom of Information Act request shines a light on how much private corporations and government agencies have been exploiting prison labor during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article was originally published in The Real News.

Curtis Ray Davis II was wrongly convicted of murder. He served nearly 26 years in Louisiana’s Angola State Prison before his conviction was overturned and he was released in 2015.

While in prison, he worked for various corporations in the private sector, making just two cents an hour. Despite the overturning of his conviction, Davis has received no additional monetary compensation for the time he spent in prison or for the thousands of hours he spent producing agricultural products, making car license plates, and working in metal fabrication.

“I spent 25 years in prison and left with $1,200, and I was innocent of the crime I was convicted for,” said Davis. “It was like being in slavery again. I was working 40 hours a week to make enough to maybe buy a bar of soap.”

Davis is now the executive director of the ReEntry Mediation Institute of Louisiana, an organization that provides mediators to develop plans with incarcerated individuals and their loved ones on re-entry—plans that include mental health services, apprenticeships, and job training opportunities.

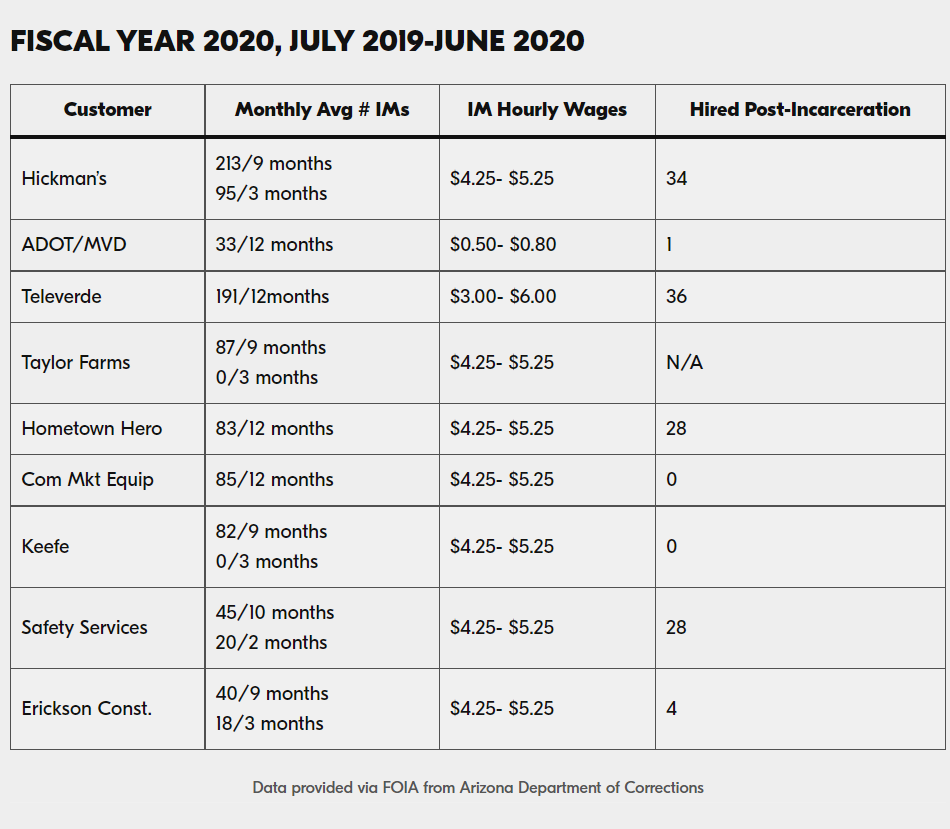

According to statistics obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, over 600 prisoners currently work in the private sector in Louisiana. Hundreds more inmates in Louisiana prisons work for state, local, or internal departments. In fiscal year 2021, private corporations spent $2,997,984.68 on contracts leasing prison labor, and the state prison labor system reports more than $29 million in operational sales (for example, the sale of agricultural products or livestock raised by state prisoners).

Around the US, people incarcerated in state and federal prisons are forced to work for private employers or government agencies for little to no pay with virtually no labor protections. All the while, the companies and public agencies involved reap the benefits of a cheap, reliable source of labor that produces millions of dollars in revenue.

Typical wages for prisoners working in private industry in Louisiana range from as low as $0.02 an hour to $0.40 an hour. Many of these workers supply labor for the private agricultural industry, primarily in livestock, soybeans, and corn.

Agricultural corporations that rely on prison labor in Louisiana include the Louis Dreyfus Company, a global corporation based in the Netherlands, which reported $33.6 billion in net sales in 2020.

Prison labor is used by multiple livestock auction corporations such as Tiger Lake Livestock, Red River Livestock, Dominique Stockyard, and the Amite Livestock Company. The lack of transparency in corporate supply chains and reliance on subcontractors makes it difficult to uncover the extent to which US corporations are benefiting from prison labor.

Elomba Ngabo, a current prisoner at Hunt Correctional Center in Louisiana, has refused to work throughout his incarceration. He’s received numerous disciplinary reports, loss of privileges, and punishments (including solitary confinement) for refusing to work for free in the agricultural fields around Angola since he was first told about the working conditions by other prisoners. Ngabo arrived at Angola State Prison in late 1997, and spent 22 years there before getting transferred to a different facility two years ago. He described lines of predominantly Black prisoners working in fields, overseen by armed white men directing them on what work to do and how to do it.

“It took away my appetite and literally I would feel sick. It affected me to the point where I began to have nightmares and couldn’t sleep at night thinking about the day they would call us out to work in the field lines,” said Ngabo.

He co-founded the organization Decarcerate Louisiana, which seeks to abolish slavery as punishment for a crime, in addition to abolishing the prison-industrial complex. The organization is supporting State House Bill 196 to abolish slavery and involuntary servitude in Louisiana.

“One can simply consider the unskilled labor that is hired to supervise the prisoners to see that no serious educational and rehabilitation instruction can successfully take place,” added Ngabo. “If public safety instruction and the morals of the people were an important value that outweighed slavery in significance, why not take at least 75% of the 18,000 acres of land that Angola Prison sits on today and, instead of using it to enforce plantation labor discipline, how about zone the land for education and rehabilitation instruction?”

More than 1 in 10 prisoners in Louisiana, 14% of all prisoners in the state, are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole—the highest rate in the US.

“You have the prison enterprises making millions of dollars off of the backs of prisoners. It’s all catered to making money, using prison labor as much as they can, and with life sentences, that means the labor is continuous,” said another prisoner at Hunt Correctional Facility in Louisiana, who requested to remain anonymous. “You still see the plantation, you’re still doing exactly what was being done in the 1800s.”

Approximately 55% of prisoners in US prisons work while serving their sentences, with jobs ranging from internal work related to food service, maintenance, and cleaning, to correctional industry programs that require prisoners to either work for private employers or, more often, for public agencies in jobs like construction or manufacturing.

Severely low wages are rampant throughout the prison labor industry, with workers being paid nothing or, at most, up to a few cents or dollars an hour—and even these wages are subject to various deductions to pay for prison and court fees.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was a major blow to many employers, including those in the private sector who utilize prison labor to manufacture their products. But the pandemic has also emboldened employers to rely more on prisoners as a cheap source of labor amid claims of a “labor shortage” and difficulties in hiring and retaining enough workers.

Early on in the pandemic, when sanitation workers in New Orleans went on strike over poor working conditions and low pay, prison labor was used as a source for replacement workers. Other employers in the sanitation and manufacturing industries cited prisoners as a pool of labor they sought to expand during the pandemic, and over 40 states relied on prison labor to produce personal protective equipment (PPE) and sanitizer products from the onset of COVID-19 in the US.

Prisoners in Iowa who produced PPE during the pandemic made on average $30 a week for 40 hours of work, while facing significant costs for necessities such as toiletries and phone call fees.

In Mississippi, prisoners are forced to work off small debts through a restitution program where the prisoners are transported to and from private employers from a jail until they cover their debts.

In Arizona, the largest egg manufacturer in the Southwest US, Hickman’s Farms, has used prison labor since the 1990s. The owner claims the practice began as a result of difficulties in hiring and retaining enough workers to do farm work. Prisoners are paid on average $4.25 to $5.25 an hour to work on the ranch, but that pay is subject to various deductions, including 30% for room and board, which leaves them with a net income of about $1.50 an hour.

Arizona’s use of prison labor in the private industry has grown significantly over the past several years, with Arizona Correctional Industries’ revenue nearly tripling from 1999 to 2020. Arizona Correctional Industries reported a revenue of more than $46.5 million in fiscal year 2020 and is seeking to reach a revenue of $65 million by 2025. Executives of Arizona Correctional Industries received some of the largest bonuses in the state in 2019, while prison workers make far below minimum wage.

The largest private employer of prison labor in Arizona, Hickman’s Farms, spent more than $7 million on leasing prisoners for cheap labor in fiscal year 2020, using on average more than 200 prisoners at any given time prior to the pandemic. The number of incarcerated workers the company used dropped to around 90 in the first few months of the pandemic until the egg ranch moved over 100 prison workers into company housing on the egg ranch itself, citing COVID-19 concerns. The company also uses prison workers through a work release re-entry program, though only a small percentage of prisoners used for labor by private employers in Arizona are provided jobs upon release.

Several prisoners formerly employed at Hickman’s Egg Ranch have filed lawsuits over injuries and maimings sustained while working at the ranch. Residents near the farms have filed complaints over the pollution and harmful chemicals produced by the company. The eggs produced by Hickman’s are sold at grocery stores around the Southwest US.