The struggle for workers’ rights in this country has been an ongoing battle for hundreds of years. At the turn of the 20thcentury, the city of Philadelphia was experiencing an influx of migrant African American workers from the Southern states, fleeing varying forms of persecution and exploitation. Since skilled positions were rarely opened to them, many of them sought work as wage laborers on Philadelphia’s busy shipping docks. One such laborer was Ben Fletcher, an African American born to formerly enslaved parents. In Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly, Peter Cole illuminates the historical relatively unknown life of Ben Fletcher and his involvement with the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies). Cole’s biographical account examines the intersection and the implications of this relationship.

The book’s main argument focuses on the racially integrated Local 8 chapter of the Wobblies and the life of one of its most important influential leaders – Ben Fletcher. In this second edition, Cole ambitiously and painstaking goes deeper in uncovering more details on the topic since the publication of the first edition in 2007. Why take on the task of the second writing of an obscure piece? Cole explains circumstances have evolved over the past thirteen years “I continued to learn more about Fletcher and the union he helped lead, Local 8” (p. xv). He attributes this phenomenon to the global reach of internet technologies where access to historical records is becoming easier to locate, and the public’s awareness around social issues are coming to the forefront. The book does not fail to deliver. Its readability appeals not only to anthropologists but to historians and to those interested in gaining a primer on labor unions and the role of racism in defining labor relationships.

The foreword written by historian Dr. Robin D.G. Kelly highlights the significance of the narrative in serving to rewrite revisionist history not only for the benefit of aspiring activist scholars but in setting the record straight. The rest of the book is followed by the preface to the second edition, introduction, and the writings and speeches by and about Ben Fletcher. The preface lays out Cole’s critique of racism and capitalism “Fletcher was one of the country’s greatest black radicals . . . as more people question capitalism and . . . its intertwining with white supremacy, the history of a working-class, black socialist and unionist is of great interest” (p. xv). The endeavor and process of writing a biography on a person where only scant records are accessible must be praised. The introduction section is that biography, followed by primary source documents on Ben Fletcher’s personal and work life. Thus, the book is not a traditional biography, which is perhaps a weakness. I do not fault Cole; instead, I applaud him for taking the risk in attempting to validate a crucial aspect of the past that might have gone unrecognized.

Cole, in describing Fletcher’s ascendency in the Local 8 workers’ union, provides context “despite the era’s rampant racism, antiunionism, and xenophobia” Fletcher, a dock labor worker with limited high school education, rose to become an instrumental union organizer (p. 2). Cole’s assertion of Fletcher’s deserving place alongside other great Black radicals is not without merit. He arrives to this summarization by analyzing the writing of prominent anticapitalism and Marxist voices and theorists such as W.E.B. Du Bois and other Black intellectual radicals on the effectiveness of Local 8 being a vanguard in accomplishing racial integration.

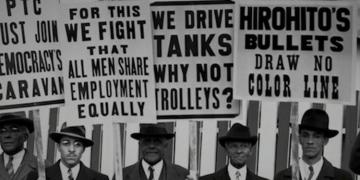

Cole’s chronicling of labor union movements demonstrates his grasp on the subject matter. His characterization of unions belonging to the American Federation of Labor (AFL) juxtapose to IWW’s Local 8 exposes the hypocrisy of the former exclusive polices favoring a specific group of workers. The Wobblies, from its inception, was considered a radical group because they were acting as an inclusive direct action solidarity organization with membership open to all “workers regardless of race, sex, color or nationality” (p. 2).

Cole’s contemporaneous insights are critical to the extent that it allows the reader to grasp the legacy of institutionalized racism still in existence today. Cole draws the reader in by connecting the dots from the past to the present; for example, he illustrates how racism is a construct utilizes in aiding the advancement of capitalism by segregating the working class. He points out the structural accumulating of wealth by big corporations when left unchecked bolstered by anti-labor laws.

Fletcher, advocating on behalf of Local 8 was still a Black man living in an overt Jim Crow racist society supported by an exploitative capitalist industry. Cole’s recollection of Fletcher’s life as a young man intertwining with Local 8 gives a bird’s eye view of Fletcher’s commitment to social activism. The evidential materials from the Writing and Speeches by and about Ben Fletcher are enlightening. Cole’s compilation substantiates the life and work of Ben Fletcher.

Cole’s incisive reporting on the coordination between corporations and the state apparatus to quash any attempts to stand up against capitalism is useful in knowing how the “Red Scare” propaganda was leveraged in undermining leftist labor union movements. “The purpose of the raids and arrests were abundantly clear: destroy the IWW” (p. 30). The dangers to progressivism ideals are real. The section in the book “The Persecution of Fletcher and the IWW” detailing these actions seems foreign to a country whose Bill of Rights was not applicable to those with an opposing viewpoint fighting for justice and equality for all. Cole reflecting on resiliency, writes that Fletcher’s commitment to the goals of the Wobblies was unparallel among other Black labor organizers of the day and ought to be recognized.

In summary, Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly (revised and expanded 2nd edition) is an outstanding book. Peter Cole deserves applause for penning a well-researched analysis on several key historical events intentionally left out of revisionist history. The research of available data in producing this book had to be a herculean effort. The inherent weakness of the text is obvious “exploring Fletcher’s ideological beliefs . . . [was] tricky because he did not leave behind a memoir, diaries, or any other personal records” (p. 58). The author in reconstructing the life events of Ben Fletcher depended on primary documents that were often missing vital details, which could have been used in building a complete picture. Nevertheless, having read the primary documents myself, I believe Cole did an excellent job of interpreting the source documents and teasing out conclusions. I appreciate the manner in how the book was fashioned, allowing the reader to investigate and to interrogate the primary source documents to arrive at one’s own conclusion. In the words of Cole, “In addition to the desire to give Ben Fletcher his due, this volume also was created to let readers decide for themselves what to think about Fletcher, the IWW, and the history of radical unionism” (p. 62). The possibilities are endless. One could conduct further research expanding upon the topic or the pursuit of a doctoral dissertation.

A copy of Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly should be read by the general public and included in the libraries of academia. It can serve as a reference in understanding “radical unionism” and in examining the legacy of racism in the context of the text or on a macro level. The book’s messaging is also contemporary and uplifting, for its depiction of the plight of the working class is still very much with us today. We ought to embrace Fletcher’s enthusiasm for direct action and solidarity. He was a staunch believer till the very end. What an example.

Brian Shuffler is a PhD student at the California Institute of Integral Studies