Dominican racial logic frequently contradicts what US scholars think they know about how race works.

“Every day decisions have to be made about what aspect of one’s identity would dominate at which moment.”

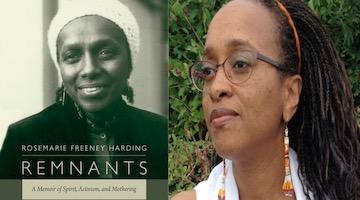

The following is an excerpt from Rachel Afi Quinn’s book, Being La Dominicana: Race and Identity in the Visual Culture of Santo Domingo. It is used with permission of the University of Illinois Press. Copyright 2021 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.

At the moment of cataloguing, racial identity appears as if it is fixed, yet those of us who live in bodies that are of mixed racial heritage experience firsthand how highly dynamic a construct race can be.

To Be Black or Latina?

“My first experience was a dilemma filling out a form at the YMCA in the US,” Yaneris tells me, describing her own challenges as an Afro-Latina in identifying herself within the social boundaries that invariably defined her as Other. She and I are sitting in her living room in Santo Domingo one evening.

“To be Black or Latina? It’s like, ‘okay, I am not fucking Latina,’” she laughs, “but I am not Black either, eh? What am I? I put Latina because geographically. . . it’s a geographic identity.” Yaneris is a dark-skinned Dominican woman in her early thirties. She has long dreadlocks that fall down her back—an exceptional aesthetic in the Dominican Republic. She agreed to participate in my research project only about six months into our friendship. She took her time deciding to trust yet another gringa researcher like myself who had come to Santo Domingo to write about race and the lives of others. My own privilege initially distanced us, and yet I soon discovered that we shared a black feminist politics that would bring us together on many issues. At the time, I did not recognize that we also shared in common an experience of straddling multiple categories of identity informed by the color of our skin. The moment of being forced to choose between two presumably disparate racial categories and racial identities that Yaneris described was familiar to me. During our conversation, I share with her how my own experiences with this type of racial “dilemma,” as she called it, inspired my scholarly pursuits. The “what are you?” question inevitably lays a foundation for each story told about mixed-race experience in the United States. Accordingly, in the multiracial movement initiated in the US in the 1990s, mixed-race experience has been perceived as an anomaly probably because it emerges in the context of middle-class whiteness. How does a mixed-race narrative of identity emerge—and play out—in the predominantly mixed-race society of Dominican Republic? Dominican racial logic frequently contradicts what US scholars think they know about how race works.

“The ‘what are you?’ question inevitably lays a foundation for each story told about mixed-race experience in the United States.”

“I have a book of Dominican races,” Yaneris tells me. “There are like, twenty-eight, and a census of slaves, from zambo to I don’t know what.. . . E’ loco,” she says, “It’s crazy.” Yaneris has reevaluated her racial identity in numerous situations throughout her life, negotiating the line between blackness and Latinidad that Dominicans embody. “I can make a list of the things that people say are ugly and that which they say are pretty,” Yaneris says, explaining that blackness is always on the former list, never the latter. “It’s like many people say we are a mix, we are pretty, we are Taínos [native people of Hispaniola] . . . but it is mostly to say that we are not black, you know?” For generations now, Dominicans have been taught that they are “indio” in color, romanticizing their Indigenous past while rejecting their African heritage, regardless of the fact that the vast majority of Taínos were killed by Spaniards in the early years of conquest. While Indigenous identity is viewed as noble, blackness—signifying Haitianness—is highly denigrated and ever suspect.

“Negra Latina . . . this is something new,” Yaneris says. The terminology is foreign in that the two racial identities might seem to cancel each other out in Dominican racial logic: a black Latina? It is “new” at a social moment in which the considerable numbers of people of African descent in Latin America has just begun gaining greater recognition. As an Afro-Dominican woman, Yaneris has often felt invisibilized in Dominican society. She says her racial identity has led her to self-censure. She keeps her observations about the daily racism she experiences to herself because her objections and concerns, along with those of other dark-skinned women in the Dominican Republic, are generally dismissed. In our interview she explains, “I can identify as Latin American but it is much easier [to identify as] as black.” Every day on the street people shout at her to get her attention, calling her by color: “Negra, how are you?” People are aware of her difference and do not hesitate to comment on it. Sometimes they use the term “morena” instead, which suggests blackness, too, though more politely. “It’s ambiguous,” Yaneris says about the term. Yet black bodies are perpetually associated with an African origin because of how we think about and recognize skin color as defining racial narratives. Black visual artists (and the white collectors of their work) have made an effort to contextualize Black art as part of a broader African diaspora, changing the meaning and value of the work and its style. African diaspora work, argues Kobena Mercer, is about representing the race, and working against a narrative of absence for black people. It is fascinating to consider Mercer’s gesture to the repeated use of the image of the African mask—a removeable face, if you will—as tying together works of “Afro- diaspora modernism,” while the Dominican muñeca sin rostro, symbolic of racial ambiguity in the African diaspora, requires the erasure of a face. It is not that Africannes can be taken on and off but rather it requires signifiers in order to be legible.

“Blackness—signifying Haitianness—is highly denigrated and ever suspect.”

For Yaneris, a dark-skinned Dominican woman, those who view her often make decisions for her about her racial identity. Yaneris faces discrimination at the intersections of blackness and queerness. As Dulce Reyes Bonilla reminds us regarding the experiences of dark-skinned Dominican women, “Day by day there is a struggle to fit in to places in which one belongs, which creates a feeling of not belonging anywhere. Every day decisions have to be made about what aspect of one’s identity would dominate at which moment.” The language of ambiguity reflects the unspoken contradictions around race and identity and challenges of belonging that Dominicans negotiate daily. We cannot avoid seeing the racial meaning of black and brown bodies even if the meaning of what we see can see/saw from one moment to the next as we articulate what we are seeing; these are the moments in which we produce mixed race.

Rachel Afi Quinn is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies and the Women's, Gender, & Sexuality Studies Program at the University of Houston.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com