Race-based medicine in the US has solidified health inequality and is bound up with indebtedness.

“Racial health is a product of social conditions that come to register at the level of the body.”

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured authors are Nadine Ehlers and Leslie Hinkson.They are editors of the book, Subprime Health: Debt and Race in U.S. Medicine. Dr. Leslie Hinkson was kind enough to participate in the interview below.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Leslie Hinkson: Our book, Subprime Health, unpacks the socio-political dimensions of continued race-based disparities in health and medical treatment. While we show that these disparities have a long history, we focus on the continuing ways Black health, in particular, is compromised in the present and how race-based medical justice has not been realized.We trace two main arguments throughout the book. First, we show that race-based medicine—which we define mainly as an entire medical system that rations and rationalizes care according to race—solidifies rather than alleviates racialized health inequality. Second, we show how race-based medicine isbound up with debt (money, goods, and services owing)and indebtedness. Race-based medicine cannot be divorced, on the one hand, from monetary debt: whatever its form, it creates the reality of monetary debt for minority groups in the United States. However, race-based medicine cannot be separated from notions of indebtedness: it is often framed as a way to redress past and current medical neglect, but often creates new moral debts in what we argue is its inability to meet the clinical obligation to “do no harm.”

“Race-based medical justice has not been realized.”

This helps readers to understand the current political and social climate in a number of ways. First, it helps inform the renewed conversation about reparations in this country, forcing us all to be very careful about how we approach reparative justice and to be mindful that reparative measures should never result in those to whom the debt is owed being framed as the actual debtors. Second, it supports the goals of the Black Lives Matter movement through revealing the ways in which banal, unspectacular practices within our society contribute even more to the degradation of Black life than those more public, overt, actions by police that end Black life in an instant. Finally, the volume reveals ways in which science and medicine are both informed by and a particular form of anti-Blackness that takes as a given the pathological nature of Black lives, of Black thought, and of Black bodies and blames this on racial inequality rather than vice versa. This tendency can be found in other institutions as well.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

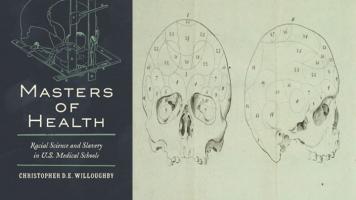

We hope that the volume as a whole reveals the ways in which race and anti-Blackness are so deeply embedded in our institutions that racial inequality is normalized. Black people aren’t genetically designed to contract high blood pressure at an earlier age and at higher rates than white people. Like all humans, they are designed to react physiologically to the world around them, including higher rates of threats to their safety and fewer resources with which to maintain physical wellness. Activists and community organizers will hopefully read our book and, if they haven’t already, begin questioning what really lies at the heart of the many instances of racial inequality we see in this country – not just in access to medical care or in the existence of racialized health disparities – but in all aspects of life and across all institutions in this society. Medicine has treated race as biological fact since its professionalization in this country in the mid-to-late 19thcentury. The fact that it has done so openly for decades with little to no self-critique should blow our minds. Other institutions in our post-Civil Rights Era have adopted more color-blind approaches to racial inequality. But can race-blind approaches ever solve a race-based problem? Subprime Health, however, also reveals that racial projects like race-based medicine can be used to cement inequality rather than ameliorate it. To those activists and community organizers, our book asks you to be brave in your actions against racism and anti-Blackness, but informed, skeptical, and cautious about which policies work best to dismantle them in specific contexts.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

There are several ideologies we hope readers will unlearn. Perhaps the primary one is the common misconception that race is a biological phenomenon. Rather, race as it relates to human populations is a socially constructed concept. Linked to this idea, we want readers to have a solid account of the ways racial health is a product of social conditions that come to register at the level of the body. Any attempt to target health according to race needs to be attentive to both of these facts. The health status of Black Americans, as we know, is produced through a wide range of past and present disparities in lived experience, racism, and unjust systems. And, while race-based or race-specific medicine is often framed as a way to focus in on these disparities, what we want readers to be attentive to is the ways race-based medicine can re-secure racial health inequalities and actually make them worse. In current times, the term White supremacy seems to have enjoyed a renaissance, both in terms of how often it is used by activists and pundits alike. Less used is the term anti-Blackness. Scientific racism, the housing crisis, our approach to crafting social welfare policies, all of these are bound up in the notion of anti-Blackness that is used to prop up White supremacy. We hope this book also causes our readers to tackle anti-Blackness straight on, not just to reject its tenets but to begin to understand the huge costs upholding this ideology has imposed not just on Black individuals and communities but on our society as a whole.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

One of our main intellectual heroes inspiring this work is W.E.B. Du Bois. As far back as the late nineteenth century, Du Bois demonstrated—in his infamous The Philadelphia Negro (1899)—that vast cleavages in racialized health have long existed in the U.S. Importantly, however, he insisted that disease, health, bodily welfare, and indeed the contours of biological life, are not related to any kind of biological “truth”: that is, they cannot be explained as the natural state of the bodies of citizens. Instead, as he showed, race-based health disparities arise from broader economic, environmental, social, and political forms of inequality and, thus, problems regarding health are “largely a matter of the condition of living”—conditions that can often be traced to the nations’ origins in settler colonialism and slavery.[1]A second key scholar we admire is Troy Duster. Through so much of his work Duster has labored to show that race-based health disparities are not biological but, rather, the biological effect of racism. Duster also issued a call to arms, pushing sociologists in particular to not just state that race is a social construction but to identify and study those sites in which that process of social construction occurs. We took on that challenge, exploring the many ways in which medical practice and biomedical research work to construct a landscape in which race is biological and thus solutions to race-based health disparities should focus on the biological as opposed to the social. We take both Du Bois’ and Dusters ideas here as launching points for thinking through the various contours of race-based medicine in our current era.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

Althea T.L. Simmons, former chief congressional lobbyist of the NAACP and director of the civil rights organization’s Washington bureau was once quoted as saying, “I can’t believe the American people are so closed-minded that they can’t see the necessity to use all our human resources.”[2]We hope that in showing the ways in which race-based medicine has worked to limit the potential of those caught in its web that we inspire a new generation of activists, researchers, and medical practitioners to reimagine the ways in which we have designated who has potential and who does not and work hard to ensure that the potential of all, regardless of race, is given free rein to be realized, unfettered by racialized notions of worth or ability. While we focus on medicine and healthcare and their power to limit that potential based on racialized notions of innate wellness, we hope that readers will extend this to include education, criminal justice, the labor market, the housing market, and our political system. We hope this volume inspires in some the courage and vision to imagine a world in which Blackness is not a variable used to predict adverse life outcomes but embraced as a significant factor in the birth, growth, and ultimate success of this nation.

Roberto Sirvent is Professor of Political and Social Ethics at Hope International University in Fullerton, CA. He also serves as the Outreach and Mentoring Coordinator for the Political Theology Network. He is co-author, with fellow BAR contributor Danny Haiphong, of the new book, American Exceptionalism and American Innocence: A People’s History of Fake News—From the Revolutionary War to the War on Terror.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com

[1]W. E. B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro(New York: Lippincott, 1899), http://media.pfeiffer.edu/lridener/dss/DuBois/pntoc.html (accessed June 10, 2013). Our emphasis.

[2]Lanker, Brian. 1989. I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America. New York, NY: Stewart, Tabori & Chang (pg. pg. 35).