Instead of succumbing to xenophobia and nativism, as with anti-Somali sentiment in Kenya or ADOS in the US, we need to pursue freedom in ways that speak to our differences.

“We arrive to how we imagine and pursue freedom in ways that speak to our differences.”

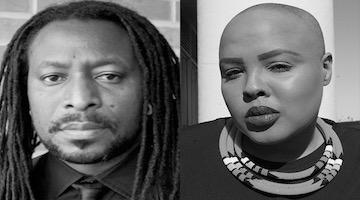

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Keguro Macharia. Macharia is an independent scholar from Nairobi, Kenya. His book is Frottage: Frictions of Intimacy across the Black Diaspora.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Keguro Macharia: After I’d completed the book, I realized it was about freedom and difference across Africa and Afro-diaspora. It seems like commonsense to say that different people approach the quest for freedom from different experiences and histories, but we so often forget this, especially when working across Africa and Afro-diaspora. This forgetting makes us anoint specific figures—usually Black men—as the leading thinkers and activists, and we gatekeep in uncreative ways. “If you haven’t read Fanon or Du Bois or Biko or Malcolm X, you can’t understand or pursue liberation.” Yet, freedom is a shared goal we work toward across difference, and freedom does not eliminate difference. I might imagine and work toward freedom because I listened to Miriam Makeba or Brenda Fassie or Nina Simone or Sweet Honey in the Rock instead of reading a famous man. We arrive to how we imagine and pursue freedom in ways that speak to our differences. In the present, across Africa and Afro-diaspora, we are faced with multiple ethno-nationalisms that manifest as xenophobia and nativism against populations deemed non-native, whether we’re speaking of anti-Somali sentiment in Kenya or ADOS in the United States. I hope Frottage shows that difference is central to working toward freedom—I know I keep repeating this. And that, as Sarah Schulman writes, conflict is not abuse. We can disagree and fight, as long as our shared goal is freedom.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

Activists and community organizers have taught me that our theories and practices of freedom must include ordinary pleasures, and that freedom is not a bundle of rights and entitlements mapped by the United Nations and other governing bodies, but the worlds we create with each other, working across difference. I think these acts of imagining together toward freedom are more explicit when we look at minoritized figures who were working outside of state formations—the colonial subjects I examine, especially Claude McKay, Jomo Kenyatta, and Frantz Fanon.

They had to imagine freedom drawing from myth and fiction, fantasy and history, collective dreaming and political organizing. Much of this work happened across difference: Kenyatta thinking alongside George Padmore and Amy Garvey, for instance, or Fanon thinking alongside the Martiniquans from his youth and the Algerians he encountered, mostly unnamed in his work, or the Jamaican McKay thinking alongside the Senegalese he encountered in France and the Moroccans he met when he lived in Tangier. How did these figures navigate difference? How did their experiences with difference teach them to imagine freedom? How might we navigate difference as we imagine and pursue freedom?

“Freedom is not a bundle of rights and entitlements mapped by the United Nations and other governing bodies.”

I think in the era of social media, we have unprecedented opportunities to work across difference, to see how other geohistories are imagining and working toward freedom, and to share imaginations and strategies, when appropriate, knowing, in very concrete ways, that our struggles are connected. I think this means working where you are while paying attention to other spaces and to the differences in those spaces.

I worry, sometimes, that freedom work in other spaces is too easily absorbed into single narratives, seen merely as an extension of local freedom work. And I think if we prioritize difference, which means we learn from and engage across multiple spaces—to the extent that it’s possible—we build something more ethical, more interesting.

Finally, Nina Simone sings, “I wish I knew how it would feel to be free,” and I kept returning to that as I wrote and revised, thinking about how to pursue something many of us have never experienced. As I was doing this, I thought of Mariame Kaba saying that some people are already living abolition. In brief moments in Frottage, I point to some freedom practices we already have, and I hope that if we can identify freedom practices that already exist, we can find ways to intensify and multiply those, even as we work against unfreedom.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

We’re in an exciting moment in African and Afro-diasporic cultural and intellectual production, where the focus is now on how to re-imagine the human so that Black being is possible. While we are drawing from a diverse group of thinkers—Claudia Jones, Edward Wilmot Blyden, Steve Biko, Audre Lorde, Frantz Fanon, Sylvia Wynter, Hortense Spillers—we are interested in jettisoning the human imagined as human, and imagining other life forms. I’m inspired by Dionne Brand, Grace Musila, Christina Sharpe, and Rinaldo Walcott to imagine ways of living and thinking a different world.

I’m hoping that Kenyan readers will imagine outside of the dominant human rights frameworks that dominate freedom work. I do not think the human imagined by human rights instruments has ever included Black people, and I think to pursue radical freedom, we have to figure out different strategies for imagining and pursuing freedom.

I am much more interested in how to imagine and pursue freedom than I am in dismantling anything. For me, this is a question of where we put our energies. We need people who dismantle and people who build. I worry that too many of us are convinced that our job is to dismantle, and not enough of us are dedicating ourselves to imagining and building.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

African and Afro-diasporic poets for continuing to dream freedom. African and Afro-diasporic musicians for giving us the sounds of struggle and freedom, and helping us move—groove, dance, sway, clap—our way to a better now. For the pleasure their work provides and the pleasure it teaches us to desire.

Under-resourced African and Afro-diasporic groups who, in pamphlets and newsletters, tweets and blogposts, instagram and snapchat images, WhatsApp and Telegram messages, continue to press toward freedom. Sokari Ekine, who dreams and makes. Mariame Kaba, who imagines and makes. Nanjala Nyabola, who imagines and creates paths. Yvonne Owuor, whose imagination builds worlds. Wambui Mwangi, whose fire burns toward freedom. Kweli Jaoko, Wairimu Muriithi, Mukami Kuria, Aisha Ali, Kenne Mwikya, Ndinda Kioko, Lutivini Majanja, Rachel Gichinga, and the many other young Kenyans imagining and creating and dreaming and practicing freedom. Their energy sustains me. Their visions inspire me. Neo Musangi, who, in the midst of our ongoing unhumaning, continues to imagine us toward freedom.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

I would love to claim it does, but I don’t think this book does that. In part, it doesn’t because the archive is historical—it focuses on the first half of the twentieth century. We can learn from those freedom dreams, but I think to imagine new worlds we need to listen for those dreaming freedom now. I am inspired by younger people across Africa and Afro-diaspora, who are dreaming freedom in art and music, in poetry and fiction.

Roberto Sirvent is Professor of Political and Social Ethics at Hope International University in Fullerton, CA. He also serves as the Outreach and Mentoring Coordinator for the Political Theology Network. He is co-author, with fellow BAR contributor Danny Haiphong, of the new book, American Exceptionalism and American Innocence: A People’s History of Fake News—From the Revolutionary War to the War on Terror.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com