This teacher has Black liberation on the menu: from Mau Mau and African communists, to Biko, Nkrumah and Fanon.

“Elkins fundamentally questions the notion of a liberal empire as it pertained to nonwhite peoples.”

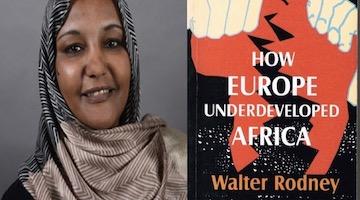

In this feature, we ask educators to list books they most enjoy teaching in their communities. Contributors include professors, graduate students, artists, journalists, organizers, activists, and other community leaders. Readers of the Black Agenda Report understand that the university classroom isn’t the only place where learning happens. Submissions therefore include lists of books that are taught at community workshops, mosques, churches, prisons, libraries, the local preschool, or even a weekly book study on one’s front porch. This week’s contributor is Nana Osei-Opare.

117 Days: An Account of Confinement and Interrogation Under the South African 90-Day Detention Law (Penguin Classics, 2009), by Ruth First & I Write What I Like, by Steve Biko.

Ruth First (1925-1982) was a Jewish South African Communist. The South African security apparatus assassinated her via a mail bomb to her house in Mozambique. While there are few first-hand accounts of women in apartheid prisons, First writes a short but powerful report of her time in solitary confinement. In these moments, First is acutely aware of the privilege her white skin affords her in jail. During her incarceration, she recognizes the special treatment she is getting in relation to black South African women prisoners. First humanizes the revolutionaries. She reveals and discusses the ways solitary confinement was intended to break a prisoner mentally. She sheds light on how the South African security apparatus sought to break her down and provide information on her comrades or force her to sign the documents, incriminating herself and others. Alongside 117 Days, I have my students read Steve Biko’s I Write What I Like (more on this text later) and show them videos of the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre and excerpts of the 1964 Rivonia trial. I teach her book in my undergraduate course.

Some of the questions I pose to my students are:

- When and how does the every day, the mundane, become torture?

- Was First’s treatment different because she was a white, Jewish woman? (p. 64, 61).

- How do we read this book alongside Biko’s critique of white liberalism?

The Making of an African Communist: Edwin Thabo Mofutsanyana and the Communist Party of South Africa 1927-1929 (Unisa Press, 2005), by Robert Edgar.

Through a series of interviews with Edwin Thabo Mofutsanyana (1899-1995), Robert Edgar provides an autobiography of Mofutsanyana’s life and the communist movement in South Africa in the 1920s and 1930s. Edgar shows the appeal of communism to black South Africans and how they viewed and understood Moscow’s role in their affairs. The book shows the limits of understanding communist parties with a solely class analysis. Edgar shows how racism continued to plague communist parties and movements in the early part of the 20th century. I teach this book in my undergraduate course.

Some of the questions I ask students to consider are 1. Why did Africans turn to communism? 2. What role did Moscow play in the internal affairs of the Communist Party of South Africa? 3. What were the racial limits of the Communist Party of South Africa, and how did Africans navigate these limitations?

I play a popular South African anti-apartheid song with this reading: “My mother was a kitchen girl//My father was a garden boy//That’s why I’m a communist// I’m a communist// I’m a communist!”

Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (Holt, 2005), by Caroline Elkins.

Elkins, a professor of African history at Harvard University, writes an authoritative and moving account of how the British colonial apparatus in Kenya created a series of gulags and camps to destroy the Mau Mau Rebellion. Elkins employs thousands of (lost) official British memoranda and interviews with hundreds of victims and white settlers to bring this brutality to light. Ultimately, Elkins shows that the British colonial government engaged in systematic human rights abuses, theft, torture, and murder against Mau Mau suspects. And she notes that many government figures overlooked these abuses and tried to cover it up. Elkins’ account also illuminates the lives of Kenyans in the gulags—what they did to survive and how they made sense of their sufferings. Throughout the book, Elkins fundamentally questions the notion of a liberal empire and notes the British and global hypocrisy to the UN Human Rights Convention as it pertained to nonwhite peoples. I teach Elkins’ book to my undergraduate students. Alongside reading the book, I have the students watch “White Man’s Country” and “Mau Mau” of the documentary, “The Black Man’s Land.” Another excellent addition to the novel is the movie, The First Grader.

Some of the questions I pose to my students are 1. What started the Mau Mau Uprising? 2. What is the link between empire and liberalism, between concentration camps and violence and the liberal empire? 3. Is there such a thing as a liberal empire?

A Dying Colonialism (1959), by Frantz Fanon.

Fanon, a key theorist of colonialism and racism, provides an account of the 1952-1960 Algerian war of liberation against the French. It is here that Fanon discusses the roles of the veil, the radio, terrorism, and inter-family relations. Fanon argues that Algerians resorted to terrorism—not because they wanted to—but because they had to counter indiscriminate French massacres and torture regimes. Unlike many liberation accounts of the period, Fanon underscores the importance of Algerian women to the liberation war. He discusses why and how Algerian women became suicide bombers and how they carried and moved weapons and money to other fighters within the French quarters. Fanon also shows how liberation wars upend social, familial, and gender norms in colonized societies. He explains that women became key players in the revolutionary war. Fanon also discusses the violent sexual fantasies French men had towards veiled Algerian women. I assign this text to my undergrads. I have the students watch the 1966 classic, The Battle of Algiers in conjunction with reading the text.

Here are some questions I pose for students:

(1) What is the link between the veil and oppression or liberation?

(2) What is the role of and tension between feminism and colonialism/imperialism?

(3) What is the double violence that Fanon speaks of?

(4) Why are doctors not protected from violence in the Algerian liberation war?

(5) What are the multiple roles of the Algerian woman in the Algerian War of Independence?

(6) What is Fanon’s take on terrorism or terrorist action? Can it ever be justified?

(7) How does the war of liberation change familial relations?

A Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare: A Guide to the Armed Phase of the African Revolution (International Publishers, 1969),by Kwame Nkrumah.

Nkrumah was Ghana’s first leader from 1957-1966. On his way to Vietnam, a Western-inspired military coup on February 24, 1966, overthrew Nkrumah’s government, and he lived out the remainder of his years in exile in Guinea, Conakry. From this abode, Nkrumah reflected upon the state of African affairs and the seeming failure of African independence. During this period, he produces A Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare. This is a lesser-known and studied work, but it contains the heart of Nkrumah’s philosophies. In it, he discusses the importance of African unity and Pan-Africanism. He breaks down the nature of neocolonialism and warns African nations and leaders to be wary of it. Nkrumah lists non-governmental organizations, western imperialism, the international monetary fund, the World Bank, and African puppet leaders as the embodiments of neocolonialism. In this text, Nkrumah breaks away from nonviolence as a viable liberation strategy. He argues that the African revolution and true African independence can only come about through armed conflict, and he outlines the ways to succeed in such a struggle.

- How does Nkrumah define neocolonialism, and what are its tools?

- How must Africans respond to neocolonialism?

- What is Nkrumah’s definition of Pan-Africanism? How does it relate to W.E.B. Du Bois'?

I Write What I Like: Selected Writings (The University of Chicago Press, (2002), by Steve Biko.

Biko was the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa. Biko powerfully critiques white liberals and their ability to be true allies. He calls on white allies to humble themselves and not seek to lead black liberation movements. Biko asks blacks why they continue to let white liberals lead their liberation efforts. He urges black people to take ownership of their struggles. Biko criticizes those who tell blacks how to respond to discrimination. Biko also questions the very nature of religion and education. He calls for a black theology and an educational structure that does not teach young black children that everything their parents did is barbaric. In this new doctrine, the black God must rise and become a pugnacious God who defends equality. Biko asks a series of questions: Where is the black God? And why has the black God allowed the white God to dominate Him for so long? Alongside Biko, I have students watch a documentary on the 1976 Soweto Uprising. Students led, orchestrated, and ran The Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa and the Soweto Uprising. So, I attempt to show my students that their activities and roles are essential in bringing about the change that they want to see.

Some questions:

- What is Black Consciousness?

- How does Biko define racism?

- What is Biko’s response to claims of black racism?

- Is Biko a segregationist?

- What is Black Theology?

- What roles did state and missionary education play in colonialization?

- How does Biko characterize white liberals and progressives, and white privilege?

- What is South Africa’s biggest problem, according to Biko?

Nana Osei-Opare is Assistant Professor of History at Fordham University.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com