“Black Brazilians have been suffering … since the establishment of slavery more than 400 years ago.”

On October 28, 2025, state police massacred close to 150 people in the Alemão and Penha favelas of Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil. The killings were the result of a “mega-operation”of 2,500 civil and military police officers to seize neighborhoods controlled by the Comando Vermelho (Red Command, or CV), described as one of Brazil’s largest criminal organizations and said to control territory containing a third of Rio’s population, more than 2 million people.

Although the operation quickly spiraled into a chaotic scene of urban guerrilla warfare, Rio’s right-wing governor Cláudio Castro hailed the operation as a success. However, police only apprehended twenty of the 100 people whose arrest warrants sparked the operation in the first place. The police quickly abandoned the favelas once the killing stopped. Most of the victims were low-level CV members and innocent civilians.

The October 28th slaughter in Alemão and Penha was the most lethal police action in Brazil’s post-emancipation history. But it also represents a continuation of decades of militarized and deadly police violence in Brazil’s numerous favelas which house predominantly Afro-Brazilian communities. These favelas emerged in the aftermath of the abolition of slavery in 1888, when the formerly enslaved with no access to land or resources set up squatter settlements near large cities. In a racist country such as Brazil, the favelas also quickly became the site of state repression against those Black communities. To date, Brazil has some of the highest cases of police violence in the region: in 2023 alone, Brazilian police killed 6,393 people, of which 83 percent were identified as Black or Afro-descendant.

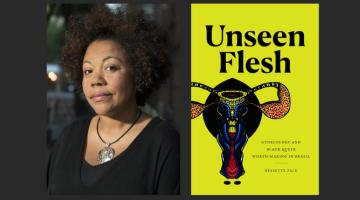

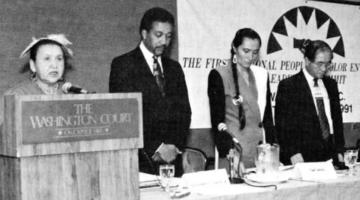

The late Brazilian intellectual and activist Lélia Gonzalez (1 February 1935 – 10 July 1994) reminds us that in Brazil, the class war is also a race war. Indeed, in a 1980 interview with the Afro-American journal First World, edited by Hoyt W. Fuller, Gonzalez notes that for four hundred years, people of African descent have been at the bottom of Brazil’s economic pyramid, supporting the country through their labour, while reaping no reward but misery, poverty, and the lash.

Lélia Gonzalez’s interview with First World provides a sober assessment of the history and political economy of race and class in Brazil–and, too, a reminder of the forms of Afro-Brazilian resistance. We reprint it below.

Blacks in Brazil: An Interview with Lélia Gonzalez

First World: For many years, the image of Brazil in the eyes of most Americans has been that of a country where racial discrimination does not exist and where people of African descent have the opportunity to rise to the top in all important areas of Brazilian life. Does that image square with the racial reality in Brazil?

Lélia Gonzalez: In terms of economic structure and social participation, Brazil could be viewed from different perspectives: From the developed and underdeveloped points of view. A large majority of the Black population is concentrated in underdeveloped Brazil… constituted by those regions where the plantation and mining activities occurred and the slavery regime perpetrated its deepest and most widespread action… In these areas we also see the emergence of a free “colored” (Blacks and mulatoos) population even before the extinction of slavery (the highest degrees of miscegenation are found in those regions). However, after slavery was abolished in 1888, the few slaves who remained and the so-called free “colored” population were, in effect, transformed into the great mass of underprivileged people who were to be exploited by the southeastern capitalism… Needless to say, the misery, chronic hunger, diseases and illiteracy are constant companions of the population. Cast aside, on their own, they find cultural resistance a way to cope with racialism .. and it is from these plantation and mining regions that the greatest expression of the Afro-Brazilian culture had their origins (The religions, the dances, the songs, the games, the festivals of junino and natalino circles the stories of the people’s imagery, etc.) In all of these expressions, the unconscious presence of distant Africa is frequently felt. In these terms, Brazilian culture as a whole is deeply influenced by the Blacks contribution. It was the task of the Black community to build the country. But from the days of slavery to the present time, we have been over-exploited by the dominant white group, the only ones to receive the benefits of our labor. The Black community… continues to be treated as slaves…

Developed Brazil is constituted by those states which reached high levels of industrialization and urbanization, such as São Paulo, Rio de Janiero, Parana, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, all in the southeast of Brazil. There, the Afro-Brazilian population is in a minority, since this region was the last to utilize slave labor. After emancipation (May 13, 1888), an abrupt social, economic and political marginalization of the former slaves occurred. Already from the middle of the 19th century, the Brazilian government had adopted a policy of stimulating a larger European immigration. The immigrant labor force ended up replacing the national and “colored” labor in the market. Thanks to the policy of “whitening,” the south/southeast of Brazil is largely populated by whites (Italians, Germans Poles, etc.). Only since 1930 have Blacks been able to work in factories in São Paulo, and this because of an interruption in the immigration process…

According to the Brazilian Constitution, we are all equal before the law. This does not occur in reality. To begin with, the Afonso Arinos law, which was created to protect the Black community against prejudice, in reality has functioned more against than in favor of Blacks who have tried to have it enforced. A case in point: A medical student in Botafogo (Rio de Janeiro) … had solid evidence of having been discriminated against by a clinic and sought justice in court. But the adverse witnesses were of such magnitude that the student, from being the accuser, became the accused (This frequently happens when Blacks seek to prosecute racists in Brazil). The prosecutor ended up threatening to prosecute the student for slander… Needless to say that student from then on was considered a subversive element by the security forces since, after all, there is no racism in Brazil. (“The Blacks know their place,” as the popular saying goes). Think of the millions who don’t even know they have rights, because the system functions in a way that keeps them ignorant. In this sense, the myth of racial democracy possesses major symbolic efficacy…

FW: Are there, in fact, people of recognizable African ancestry in the top ranks of government, industry, religion, society and the arts in Brazil?

LG: The Black community of Brazil does not participate in the political life of the country because they don’t vote. Since the elaboration of the Republican Constitution in 1891, the illiteracy has its highest incidence in the Black communities… Blacks who take part in the competitive process, even if they have similar qualifications and capabilities, are frequently by-passed in favor of white competitors. This inequality is present in all levels of society. It is no coincidence that an absolute majority of Black Brazilians form an integral part of the growing marginalized mass. Even though statistical data about open employment is lacking in Brazil, the truth is that the vast majority of Black people live from expedients (sporadic work), that is, working from 50 to 100 days a year, unprotected by labor laws…

It is clear that there are Blacks who are co-opted by the system: they are successful and well off. But what does it mean to be co-opted?— It means that you forget your own cultural origins, as well as the misery and abandonment in which the Black community lives. It means internalizing and reproducing, at different levels, the values of the dominant white race, including its racism. It means being used as an isolated example to confirm the “non-existence” of racism and to perpetuate the myth of racial democracy. It means losing your own dignity and your own identity. It means committing suicide as a human being, as a subject, to become an object. This is the price that is paid to play the game of the system .. to continue to be controlled and manipulated … And when one attempts to react positively to confront this state of affairs, condemnation comes from all fronts. If the reaction is characterized by cultural resistance, all kinds of labels are pinned on it, such as “alienation,” “primitivism,” “inferiority,” “backwardness,” “ignorance,” etc.. If the reaction is of the political denunciation/confrontation type, there are two accusations which are received: “reverse racism” (which implies that one-sided racism is valid) and “subversion.”

FW: Exactly when and why did the United Movement Against Racial Discrimination in Brazil begin? What is its current status?

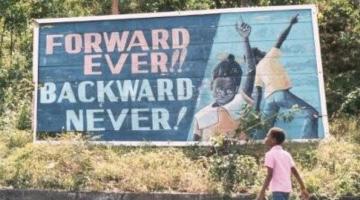

LG: Its birth stems from the historical need to synthesize the two forms of reaction mentioned earlier— cultural resistance and political denunciation/confrontation. In this way, it becomes the very expression of a new political consciousness… The developed areas of Brazil today are much different from what they were 15 years ago. The multi-national corporations control the national economy and make subsidiaries of the small- and middle-size businesses. They maintain a hegemony that is felt even in the economically poor regions of the northeast. Therefore, the process of racial (and sexist) sectarianism in the labor force presents the most obvious contradictions precisely in the most advanced centers of the country…. The concrete reasons that led to the creation of the Movement symbolize facts of the day-to-day life of Blacks in Brazil. In a demonstration on July 7, 1978, in São Paulo, its creation became effective. The torture and assassination of a Black worker by the São Paulo police, on the one hand, and the expulsion of four Black youths from a volley ball team at the Club de Regatas Tiete, on the other hand, brought about this public demonstration. It was organized and carried out by a group of Blacks from São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, representatives of cultural and political organizations. Workers, students, liberal professionals, and the like, united to denounce the practice of political, social and economic marginalization of Blacks, beginning the criteria of exclusion of a racist and authoritarian society.

FW: What is the overall goal of the United Black Movement Against Racial Discrimination in Brazil?

LG: The fundamental proposal of the Movement consists in the mobilization and organization of the Black community, as the centralizing organism of its struggles, and to expose every single act of discrimination against the community. There will be “centers of struggle” -- basic units of the Movement — in every locality where there are Blacks (slums, housing projects, “terreiros” of umbanda and candomble, churches, work sites, schools, samba schools, etc.), raising basic issues, informing, sensitizing and organizing the entire Black community.

The objectives of the Movement were established in a charter of principles… This charter proposes not only specific goals that affect the community as a whole… Registered in its bylaws, in general terms, is the following: from the centers of struggle emerge the elements that form the regional and state-wide chapters, as well as the elements that will form the national executive commission. Each commission is subdivided into sub-committees (publicity, press contacts, and finances). From the date of the demonstration in São Paulo to the general assembly at Rio de Janeiro in September 1978, the Movement spread to other states, such as Mines Gerais, Bahia and Espírito Santo.

Because Brazil is such a large country (with 3,275,510 square miles, it is some 250,000 square miles larger than the continental United States), it is easy to perceive the extensive task the Movement faces. And we are not only dealing with purely geographical difficulties but also with different levels of problems, among which are the following:

The conditions of material existence of the Black community relate to psychological conditioning that has to be identified and exposed. The different degrees of domination of the various forms of economic production seem to coincide on one point: the reinterpretation of Aristotle’s theory of “the natural place.” From the colonial period to the present time, we perceive a gross separation insofar as the physical space occupied by the dominator and the dominated is concerned. The “natural” places for the white dominant groups are healthy living conditions, spacious homes, situated in the most picturesque parts of the cities or countryside, all adequately protected by different forms of policing. From the time of the “Big House” and the “Sobrados,” to the big residential buildings of today, the criteria have always been the same. Now, obviously, the “natural” place for the Blacks is at the exact opposite extreme: from the “senzalas” to the slums, “corticos,” in various swamps and “housing projects”… What is prevalent are families piled together in cubicles whose conditions of health and hygiene are of the poorest nature. In addition to all this, policing is a constant presence, except that they are not here to protect but to repress, violate and intimate. From this you can understand why the other “natural” places for Blacks are the prisons and mental institutions. The systematic police repression has as second objective the spreading of psychological submission through fear…. What is visualized is the prevention of any form of unity in the dominated group by using every measure to perpetuate internal division.

The system is benefitted by maintaining such conditions: the cheapest labor possible remains at its disposal, since the Black community is nothing but a deprived mass to be used as needed by the system. If Blacks don’t work, there are the prisons to guarantee “progress and order.” Unemployment for the Black Brazilian means imprisonment for vagrancy … During their raids, the police demand that Blacks (and only Blacks) present job I.D. cards: if the cards are not signed (by a white boss, of course), they are jailed, tortured and forced to confess to crimes they have not committed. This happened when they are not simply assassinated by the police… There is very little difference in the practice of demanding the job I.D. cards in Brazil and the so-called passbooks in South Africa. And it is important to say that the amnesty movement of Brazil has never looked at the torture of Blacks, which is not a new fact in Brazilian history. Black Brazilians have been suffering this since the establishment of slavery more than 400 years ago…

Blacks in Brazil: An Interview with Lélia Gonzalez, First World 2 no. 4 (1980)