The narrative of famine in the Tigray region of Ethiopia was repeated uncritically by the media and was amplified by people who were on board with the U.S. regime change plot against the Ethiopian government.

Stephen Were Omamo served as Director of the World Food Program in Ethiopia from 2018 to 2021. From that viewpoint he saw the international community misrepresent facts on the ground in the two-year Ethiopian civil war in service to what he called the “good-guy TPLF vs. bad-guy Government story line that was already fully developed and circulating globally” shortly after the war began in November 2020.

The US and its Western allies had designated Tigrayans and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) as the good guys, what Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman called “worthy victims” in Manufacturing Consent. The unworthy victims were the Amhara and Afar, people of Amhara and Afar Regional States, which had been invaded by the TPLF.

Omamo calls his book “At the Center of the World in Ethiopia” because, he wrote, he wanted to instill a sense of worth and dedication in his team, but also because:

“Within the United Nations, Ethiopia hosts not only the largest UN country team, but also the UN Economic Commission for Africa, the UN Office to the African Union, and the UN Special Representative for the Horn of Africa. In Africa – partly because it is home to the African Union and 115 embassies and diplomatic missions, and partly because of the wide and deep reach of Ethiopian Airlines – the idea that Ethiopia’s capital city, Addis Ababa, is the “capital of Africa” is truly meaningful. And at global level, there is no trend – positive or otherwise – that does not have a massive expression in Ethiopia: the youth bulge, urbanization, migration, democratization, decentralization, income growth, shifting diets, supply chain integration, capital-intensive technology change, expanded use of digital devices and internet access, burgeoning private enterprise, climate change and variability, civil war, rising public debt, female genital mutilation, and more. Name it, it’s there, in a big way.

Everything we were seeing and doing in Ethiopia spoke powerfully to global issues.”

When I read that it caused me to return to a thought I’ve had many times since returning from a trip to Ethiopia and Eritrea for much of the spring of 2022—that a major war and catastrophe had occurred, that the US had played a central role in it by supporting the “good-guy TPLF vs. bad-guy Government” narrative, that as many as half a million African people may have died, that more than 5 million more had been displaced, and that most Americans knew nothing about it.

Of course, American ignorance, some say innocence, is nothing new. Years after the US attacked Iraq in 2003, surveys showed that a majority of Americans couldn’t find Iraq on a map and still believed that Saddam Hussein had possessed the “weapons of mass destruction” alleged to justify the war.

However, most Americans at least knew that there had been a war in Iraq, whereas very few even knew that there had been a war in Ethiopia. If they knew anything—or rather, believed they knew anything—it was that the people of Tigray were dying of hunger because the Ethiopian government was cruelly blocking food aid trucks traveling there. This was, Omamo writes, “total fabrication,” and the mostly white, all-Western “donor representatives” and top WFP and other UN officials in Geneva have simply moved on:

“Nobody has admitted that the ‘people are dying of hunger in Tigray’ narrative was total fabrication. There were no consequences. There are never any consequences as the ‘international community’ recycles itself from crisis to crisis. Incompetent and unethical people who lie, distort, and mess up can just walk away and do the same thing somewhere else. To me, that is annoying. For the world, it should be unacceptable.”

Although Omamo left Ethiopia at the end of 2021, he confirmed much of what I was able to witness and report when I traveled to Ethiopia in the spring of 2022. The suffering in Amhara and Afar Regional States due to invasion by the TPLF was horrible. Camps for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) lined the sides of the A2 highway, Ethiopia’s central north/south artery in Amhara Region, and in the city of Sekota and its surrounds near the northern border between Amhara and Tigray. People needed food, water, and medicine and they were deeply traumatized.

In Afar Regional State, which had also been invaded by the TPLF, there were IDP camps all up and down the main highway going north/south from Addis Ababa to Tigray. In Semera, Afar, I visited a hospital that had been overwhelmed first by wounded Afar soldiers and then by wounded, sick and malnourished Afars fleeing the TPLF. I visited an IDP camp of an estimated 30,000 Afars where three children were dying every day for lack of clean water. The hospital authorities feared that a measles outbreak would sweep through the camps killing far more children, but I was told that a team showed up to mass vaccinate shortly after I left.

I was not able to witness suffering in Tigray because the government was not allowing any journalists into Tigray at that time. A fellow journalist and I were told that they didn’t want us to risk harm there, but in any case, I knew that my reporting was incomplete because I hadn’t seen Tigray.

What I knew and reported was that the catastrophic consequences of the TPLF invasions of Amhara and Afar were barely covered by the Western press, mentioned only in passing, but catastrophe in Tigray and, most of all, alleged famine due to government cruelty, were reported incessantly.

Stephen Were Omamo chose not to name names in his book, but I won’t hesitate to say that World Health Organization Director Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, himself a Tigrayan and former top TPLF official, was the most prominent of top UN personnel repeating that “Tigray is starving, a Tigray genocide is underway” day after day, week after week, for two years. He is among those whom Omamo describes as walking away without consequence.

Omamo confirms what I was unable to see—great suffering and need for humanitarian assistance in Tigray—but also writes that, when speaking to a European ambassador who wanted to know about the Tigray famine story he’d heard over and over:

“I could only repeat my usual response. Without doubt, there was deep food insecurity in Tigray. But there was no evidence of famine. While I did not say it, I certainly thought, ‘And the finding of ‘near famine’ should have been interpreted with more care and responsibility.’ I also stressed that this was a crisis that extended well beyond Tigray, and that WFP Ethiopia’s most proximate fears at that time were for populations in TPLF-besieged parts of Afar and Amhara regions where there had been no support at all since March-April 2021. No reaction.”

The war was no doubt prolonged by Western repetition of the “good-guy TPLF vs. bad-guy Government” because it gave the TPLF reason to keep fighting, knowing that the West was with them; we may never know what sort of support may have been provided beyond political, diplomatic, and narrative support, but near the end, when government forces were close to winning, demonstrators at a large rally in Addis held up signs that read, “Respect Our Sovereignty” and “US Stop Sucking Our Blood.”

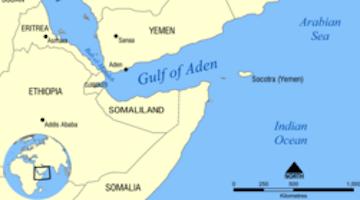

In the end US Special Envoy to the Horn of Africa Mike Hammer showed up to escort the TPLF “negotiating” team to Pretoria in a US military aircraft to meet with the government team, and no doubt made its demands heard in the background. Government forces, with the help of Eritrean forces, had clearly defeated the TPLF, but their victory was termed a “permanent cessation of hostilities” so as to allow the US and the TPLF, its longstanding client, to save face.

Another sad consequence of the fabricated “Tigray famine” narrative was, Omamo writes, the destruction of trust relationships between humanitarian agencies and the Ethiopian government, which saw itself repeatedly slandered with the “Tigray famine” fabrication:

“Sadly, we can also say with certainty that because of the way the IPC [Integrated Food Security Phase Classification] update report was handled, the short-lived but highly promising IPC process in Ethiopia is dead and buried. That is tragic. It took years to build it up. Also probably dead is the Humanitarian Response Plan as a shared vision and operational platform between the Government and humanitarian partners for joint humanitarian action in Ethiopia. The loss of trust and credibility is deep. That, too, is tragic.”

Ann Garrison is a Black Agenda Report Contributing Editor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. She can be reached at ann(at)anngarrison.com.