The Black Panther Party Has Never Been More Popular, but Actual Black Panthers Have Been Forgotten

The name Black Panther is a box-office draw, but can cinematic sympathy be extended to the Panthers who are still living and breathing in this country’s prisons?

“In the last two decades, at least eight Panthers have died in prison.”

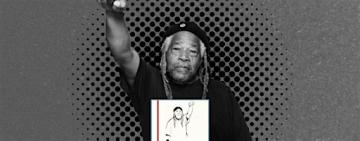

On October 7, 2020, Jalil Muntaqim exited the Sullivan Correctional Facility in upstate New York a free man. A member of the Black Panther Party and its more militant, clandestine offshoot, the Black Liberation Army, Muntaqim was 19 years old at the time of his 1971 arrest, which was followed by his conviction three years later for the murder of two NYPD police officers, Waverly Jones and Joseph Piagentini. After nearly a half-century behind bars and over a dozen parole requests, Muntaqim’s parole was approved last September, one month before his sixty-ninth birthday.

The country has undergone considerable changes during Muntaqim’s 49-year incarceration, not the least of which being the widespread popularity, veneration, and commodification of the Black Panther Party. The examples abound: Beyoncé’s 2016 Super Bowl performance, in which the singer and her dancers dressed in Panther-influenced attire; the Marvel superhero film Black Panther; the Black Panther Party graphic novel; the Levi’s “Black History Month” collection, featuring hoodies and T-shirts emblazoned with “Black Panther graphics”; and, of course, the Oscar-nominated film Judas and the Black Messiah, a dramatized retelling of the 1969 police murder of Illinois Black Panther chairman Fred Hampton.

“The country has undergone considerable changes not the least of which being the widespread popularity, veneration, and commodification of the Black Panther Party.

But what do veteran Panthers—some of whom are now at an advanced age and fighting to make ends meet after spending more than half their lives in prison—think of this recent boom in artistic and commercial interest?

“They exploit the name and the legacy of the Black Panther Party,” Muntaqim told me, “without any credence or any true thought to the idea of those who are still suffering from Cointelpro convictions, and those of us who are elderly now and suffer from age and without any means of surviving. Our circumstances, in terms of being exploited in the name of the Black Panther Party, are horrendous.”

The U.S. Counterintelligence Program, or Cointelpro, was a notorious FBI operation that employed covert and illegal means to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” alleged subversive political organizations throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Led by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Cointelpro targeted Communist and socialist organizations, the American Indian Movement, Puerto Rican independence groups, Vietnam War protesters, and such leaders as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. But by the late ’60s, Hoover’s FBI had zealously directed its energy toward destroying what it deemed “militant black nationalist groups,” particularly the Black Panther Party.

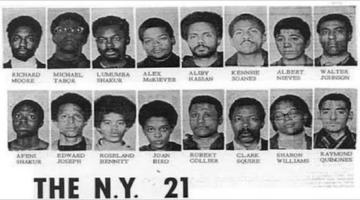

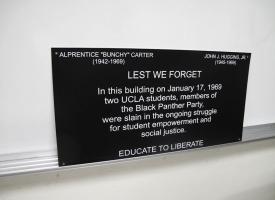

Labelled by Hoover “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” the Black Panther Party had, by 1969, been the target of 233 Cointelpro actions, which varied from provoking rivalries within the organization to installing undercover agents and agents provocateurs. Until its accidental discovery in 1971 by an activist group digging through files in an FBI field office in Media, Pennsylvania, Cointelpro had contributed to the deaths of at least four Panthers, including Fred Hampton and Mark Clark on December 4, 1969, and the imprisonment of dozens of Panthers. Though some have since been paroled or had their convictions overturned after spending decades in prison, many veteran Panthers remain incarcerated to this day. So while the Black Panther Party is now seeing its greatest popularity (and profitability), the still-living Panthers—whether newly freed or still incarcerated—see little to no benefit, from Hollywood or other entertainment industries.

“They’re not providing any services or support for these aging Panthers,” Muntaqim says, “but they’ll take the name; they’ll take the legacy of [the Panthers] and exploit it, profit off of it.”

“Someone makes a lot of money off it, and nothing goes to the families of the fallen,” elder Panther and former prisoner Sekou Odinga tells me. “Nothing goes to those that are locked up, fighting for their lives.”

“The still-living Panthers—whether newly freed or still incarcerated—see little to no benefit.”

Odinga was leader of the Black Panther Party’s Bronx chapter, founded in 1968, and later worked with the Party’s International Section in Algeria. In October 1981, Odinga was captured by authorities and charged in connection with the attempted robbery of a Brink’s armored trunk in Nanuet, New York, during which two police officers and a security guard were killed; he was also charged with aiding in the escape of Assata Shakur from a New Jersey correctional institution in 1979. After serving 33 years of a 25-to-life sentence, Odinga was released from New York’s Clinton Correctional Facility on November 25, 2014. He was 70 years old at the time of his release.

Though Odinga and Muntaqim have been recently granted the opportunity to live out their final years among family and friends, over a dozen Black Panthers and other Black liberation activists remain incarcerated, including Russell “Maroon” Shoatz, Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown), Kamau Sadiki, and Mutulu Shakur (Tupac’s stepfather). Many of these incarcerated men—all over the age of 60—have faced intensifying health crises, heightened by the Covid-19 pandemic. Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has been incarcerated since 1981, tested positive for the virus in March, in addition to suffering from congestive heart failure and an excruciating skin condition. Last November, Shoatz was diagnosed with Covid-19 and stage-four colon cancer. Shakur also contracted Covid-19 last November, while undergoing treatment for advanced bone marrow cancer.

Like Odinga, Sundiata Acoli was affiliated with the New York Black Panthers and the Black Liberation Army. Acoli is currently serving his forty-ninth year of a life sentence, after his conviction for the May 2, 1973, shootout on a New Jersey turnpike that left State Trooper Werner Foerster dead. A college-educated mathematician and NASA computer analyst before joining the BPP, Acoli, now 84 years old, was given the possibility of parole after 25 years, but he has since been repeatedly denied parole, despite his record of good behavior, his expression of “regret and remorse” for his involvement in the shootout, and his advanced age. Acoli has suffered from myriad health complications, including hypertension, emphysema, glaucoma, and advancing dementia. He, too, narrowly survived after contracting Covid-19 last year.

In the last two decades, at least eight Panthers have died in prison—most recently Romaine “Chip” Fitzgerald, who died in a California prison on March 29, at age 71. Having been incarcerated for more than 51 years, Fitzgerald was the longest-serving Black Panther in American history.

“Acoli is currently serving his forty-ninth year of a life sentence.”

While many people today might be familiar with the co-founders of the Oakland chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale (himself represented in another Oscar-nominated movie this year, Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7), many of the above names remain unfamiliar to those who are just learning about the history of the Black Panthers, whether as students, activists, or moviegoers. And these people are due the same reconsideration that Hollywood has recently afforded Seale and Fred Hampton, whose often violent legacies are now being interpreted with greater sympathy by audiences and movie executives alike, amid growing awareness of the depths of the Black struggle for equal rights.

Matt Meyer—an author, editor, educator, and longtime peace activist, who has worked closely with and on behalf of political prisoners—worries about the erasure of these surviving, imprisoned Panthers. “With this whole slew of material coming out in recent years, it’s as if the Black Panther Party began and ended in the city of Oakland—and began and ended with the person of Huey Newton and maybe Bobby Seale,” Meyer told me. “That wasn’t true then, and it’s not true now. Only an extremely simplified and mythologized version of history can so easily invisibilize the fact that we’ve got so many Panthers still in prison today.”

Still, some of these formerly incarcerated Panthers acknowledge some benefit to be gained by this current interest in the Black Panthers. “Every time somebody mentions the word ‘Panther,’ we examine it and we check it out,” Bilal Sunni-Ali told me. A founding member of the New York Black Panthers, Sunni-Ali has been arrested twice, once in 1969 and again in 1982, for his involvement with the BPP. He has been free since 1983 and has gone on to advocate for still-incarcerated Panthers and other political prisoners, in addition to his work as a world-renowned musician and member of Gil Scott-Heron’s Midnight Band. “If someone is giving out false information, it gives us an opportunity to correct that false information,” Sunni-Ali said, “and point to where people can get correct information.”

Odinga, too, acknowledges that the current popularity of the Panthers can be used as a “teaching opportunity”: “If people are interested, they can ask questions. Or you can challenge people and challenge the things you didn’t like, put forward what you think it was, and have a discussion where people can learn the truth, or at least get another perspective.”

“Odinga acknowledges that the current popularity of the Panthers can be used as a ‘teaching opportunity.’”

As veteran Panthers and former prisoners, Muntaqim, Odinga, and Sunni-Ali have taken on the responsibility not only to represent the Black Panther Party accurately, but to advocate for their imprisoned comrades. Odinga is regularly invited to give speeches and lectures on political prisoners in the United States; Sunni-Ali works on campaigns to free Jamil Al-Amin; Muntaqim is founder of the political prisoner advocacy organization Jericho Movement; and Odinga and Meyer serve on the coordinating committee for “Spirit of Mandela.” Initially proposed by Muntaqim, Spirit of Mandela plans to hold an international tribunal on October 22 to 24, with the goal of “charging the United States government, its states, and specific agencies with human and civil rights violations against Black, brown, and Indigenous people.” It is being held in commemoration of the seventieth anniversary of “We Charge Genocide,” when actor and activist Paul Robeson and Civil Rights Congress executive director William Patterson delivered a petition to the United Nations accusing the U.S. government of genocide against American Blacks.

The recent glorification of the Black Panthers in popular culture, then, stands as a test for audiences, particularly non-Black audiences. Are they willing to sympathize with the Panthers only if they’re presented as long-dead historical actors? Or can they extend that sympathy to the Panthers who are still living and breathing in this country’s prisons?

For anyone who might be just learning about the history and repression of the Black Panther Party—whether from the latest books, music, or feature films—and wants to get involved in calling awareness to currently incarcerated Panthers, Meyer offers a simple, straightforward place to start: “Write a letter [to political prisoners], saying, ‘I know you’re out there.’ Send a tweet or text a friend, saying, ‘Let’s not just go see the latest movie; let’s spread the word about the people who are still inside. All of that has one central theme: Organize.”

“Organize your friends and your family and your organizations,” echoes Odinga. “Your churches, the people that you be around, on all your social media—you can put information out there about the struggle, about the brothers and sisters who are still locked down, still struggling for their freedom.”

Santi Elijah Holley has contributed to The Atlantic, The Guardian, The Economist, Tin House, VICE, and elsewhere. He is the author of Murder Ballads and the forthcoming An Amerikan Family. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

This article was previously published in The New Republic.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com