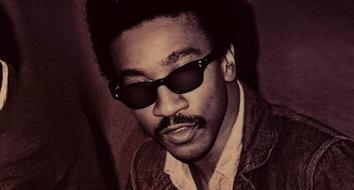

To commemorate 100 years since the birth of former political prisoner Martin Sostre, the Black Agenda Report Book Forum interviews Garrett Felber, A Visiting Fellow at Yale University who is currently writing a book about Sostre. The book is called, We Are All Political Prisoners (under contract with the University of North Carolina Press).

Roberto Sirvent: You’re currently writing a book about Martin Sostre. What led you to pursue this project?

Garrett Felber: A decade ago I was beginning research for my dissertation on the Nation of Islam’s organizing in prisons and I came across a letter to Malcolm X from a Muslim at Attica Prison. He was requesting Malcolm X testify as an expert witness in an upcoming trial concerning the religious rights of imprisoned Muslims. In the letter, he mentioned others being tortured in solitary confinement, one of whom was Martin Sostre. I looked up his name and found a barebones Wikipedia page documenting his frame-up and political imprisonment years later in Buffalo for running a revolutionary bookstore. But there was nothing about this earlier period or his life after getting out of prison in 1976.

I wrote him a letter asking to interview him. What I got back blew me away. He sent an envelope full of documents, including a revolutionary Black newspaper he wrote from solitary confinement in 1971. Also enclosed was a newspaper article from twenty years later, with a photograph of Sostre and co-organizer Sandy Shevack seated with children at a daycare graduation in Paterson, New Jersey. “The enclosed documents contain more information than I could possibly convey to you via email or phone,” he wrote.

We exchanged letters briefly, but he had a stroke shortly thereafter and was no longer able to write. I stayed in touch with his family after he passed away in 2015 at the age of 92, and continued to learn more about his life and the impact he had on prisoner organizing and Black anarchism. I began to appreciate what a unique political thinker and revolutionary strategist he was, one still little known even within many anarchist and abolitionist spaces.

In the article about the daycare center he co-founded, Sostre is quoted: “People dream. Sandy and I objectified our dream.” Part of what struck me was his reluctance to narrate his life and his preference to let his actions speak for him. The more I learned about him, the more I understood the significance of what he sent me, and the act itself. It felt as if he had entreated me to do the labor of understanding his life through his work rather than simply his words about it. I hope this biography does justice to that life, which is no small task.

RS: What influence did Martin Sostre have on the Black anarchism movement?

GF: It would be difficult to overstate Martin Sostre’s influence on the development of Black anarchism. Virtually any genealogy of contemporary Black anarchism leads back to him. Sostre is the first self-identified anarchist that I know of who defined his anarchism principally through its meaning to Black liberation. He came to this political framework through his specific life experiences: as a Black Puerto Rican growing up in Depression-era Harlem; as a prisoner who was politicized by Puerto Rican revolutionary nationalist Julio Pinto Gandía and helped launch the first organized prison litigation movement as a Muslim in the Nation of Islam; as the owner of a revolutionary bookstore that was targeted following the 1967 rebellion in Buffalo; as a plaintiff in landmark lawsuits against the state; and as prisoner of war organizing for revolution from solitary confinement.

Although he did not identify as such until 1973, he traced his anarchism to the streets of Buffalo during the 1967 revolt. In fact, he later wrote that he saw himself as “an anarchist by nature all my life.” His Afro-Asian Bookshop on Jefferson Ave. was at the heart of the rebellion. It was a site of politicization and refuge for people in the streets during the uprising, and according to Sostre, a small group of anarchists met there each night to discuss what was happening outside. “The full impact of . . . how beautifully fulfilling anarchism is didn’t hit my consciousness till the long hot summer of 1967,” he reflected.

Sostre understood anarchism as a natural human tendency towards spontaneous organizing that was crushed and coopted under hierarchal, dogmatic, party-line Marxist and Black nationalist formations. He regularly read, recommended, and gifted books by Berkman, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Voline, but he was still reluctant to identify himself with anarchism because he worried it would not resonate with poor young Black people, who he saw as the “detonators” of the revolution. He was also troubled by the apparent tension between anarchism and Black national liberation: “I am reluctant to categorize myself as an anarchist because although my philosophy of action and direct violence (along with other acts) against the State to seize and ‘liberate’ areas in various parts of the country and to use these ‘liberated areas (fortified communes?) as bases from which to ‘wage our war of liberation,’ the objective of this struggle is to establish a ‘black nation’—which negates anarchism.” Nevertheless, a year after writing this, he began calling himself a “revolutionary anarchist.” He seems to have settled on “revolutionary anarchist” (my emphasis) not because he thought there was some form of anarchism that was not revolutionary, but because he understood “the word ‘revolutionary’ is in” and wanted something that Black and Latinx youth could identify with.

The foundation of Sostre’s anarchism was his experiences within the Black radical tradition, particularly in prison. It should not surprise us, then, that the two most important bridges between Sostre and contemporary Black anarchism are Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin and Ashanti Alston, both of whom Sostre impacted both directly and indirectly from inside. Sostre mentored Ervin directly over a two-week period in 1969 when the two overlapped in federal detention in Manhattan, after which Ervin became an anarchist, a jailhouse lawyer, and even modeled his defense committees after Sostre’s. Alston read Sostre’s writings, seeking them out at the Tamiment Library after he was released in the 1980s; he later organized on behalf of political prisoners with Sostre in the 1990s. Both emphasize how important it was for them to come across an anarchism rooted in Black liberation. “I did not need the traditional canon on anarchism,” Alston said. “I needed to hear it from some Black folks who I had a lot of respect for.”

All three—along with Kuwasi Balagoon—became important forebears for contemporary Black anarchism. It was no coincidence that all of these revolutionaries—Sostre, Ervin, Alston, and Balagoon— were political prisoners who moved through the Black Panther Party and/or the Black Liberation Army (BLA) at some point. I think persuasive arguments can be made for the influence of both organizations in this lineage as well, as well as the centrality of the prison as a crucial site of Black anarchic formations.

RS: How did Sostre connect everyday forms of individual resistance to larger collective struggles against capitalism, imperialism, and anti-Blackness?

GF: This question immediately brought to mind a passage from a letter Sostre wrote a year before he got out of prison: “The line is drawn: either you are a cooperator with the oppressor in your own oppression and dehumanization, or you are a resister. If you won’t stand up for your own personal liberty, human dignity, and self-respect, all that rhetoric about liberating other people is just bullshit rhetoric. The struggle for liberation begins with the individual whenever and where she or he is oppressed.”

Sostre believed everywhere was a site of struggle. He organized wherever he was. When imprisoned, he sued the state, formed prisoners’ unions, helped people with their legal paperwork, and organized study circles. When outside, he opened a revolutionary bookstore, transformed abandoned buildings into affordable housing and community spaces, and organized tenants against landlords.

For liberation to begin with the individual, as he suggested, individual resistance must be connected to the liberation of all oppressed people. Here is one example from Sostre’s life: For six years at least, Sostre refused rectal “examinations” when leaving or entering solitary confinement. Prison officials claimed these “cavity searches” protected against contraband. Sostre understood they were meant to dehumanize and degrade, and he resisted to maintain his dignity and personhood. But his defiance was also linked to collective liberation. He organized strikes against these sexual assaults, raised consciousness about them through lawsuits and in courtroom testimony, and linked his individual resistance to global national liberation struggles.

Drawing a parallel to North Vietnam, Sostre described his refusals as a one-person version of the National Liberation Front (NLF): “Mine is on a personal level, whereas the Vietnamese were fighting on a national level. They were fighting against the strongest and most developed and richest country in the whole world. That’s equivalent to me fighting against the whole goon squad in the solitary confinement unit at Clinton prison. I want to show the forces and powers that I use—physical, mental, political, and legal—in order to eventually subdue the enemy and register victories, and at the same time keep from getting killed.”

He considered his resistance to sexual assault and assertions of bodily autonomy and identity as simultaneously necessary to his own personal freedom as well as symbolic of the worldwide struggle.

RS: Can you please share a little about the upcoming “Martin Sostre at 100” event taking place in March?

GF: Thank you for highlighting this. The event is a celebration of Martin Sostre’s life and legacy on what would have been his hundredth birthday, hosted by the New York Public Library on March 22-23, 2023.

The first evening will be held at the Harry Belafonte 115th Street Library, which was Sostre’s neighborhood branch growing up. We’ll be screening the short documentary film Frame-Up! The Imprisonment of Martin Sostre (Pacific Street Films, 1974) and hosting a discussion with some of Sostre’s comrades and defense committee organizers—Jerry Ross, Antonio and Sylvia Rodríguez, Sandy Shevack, and more—moderated by William C. Anderson.

The second night, at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, will feature a keynote conversation between abolitionist educator and organizer Mariame Kaba and imprisoned intellectual and prison (dis)organizer Stevie Wilson. We’ll also hear a panel on the Imprisoned Black Radical Tradition with Laura Whitehorn, Jose Saldaña, and Masia Mugmuk, moderated by Orisanmi Burton.

Finally, we’re organizing an exhibition on Sostre’s commitment to radical political education which will include a life-size replica of the Afro-Asian Bookstore-in-Exile (AABE). The AABE was a continuation of Sostre’s revolutionary bookstore in Buffalo during his incarceration and lasted for nearly three years at the University of Buffalo student union and in various iterations on college campuses across the country.

Keep an eye out all March—which we at the Martin Sostre Institute (MSI) will be commemorating as “Martin Sostre Month”—for other ways to learn about his life and work.

RS: As you were conducting research for the book, what were some ways that people described the influence Sostre has had on them?

GF: I love this question! Before I answer, I want to acknowledge what an incredible experience it has been to learn from so many people about Martin Sostre’s life and its lasting impact on them. I’ve conducted around 70 interviews over the last three years, and it has profoundly changed my thinking and organizing. I am grateful to them in so many ways.

One striking continuity across Sostre’s many decades of organizing on both sides of prison walls was his emphasis on young people’s revolutionary capacities. Part of the reason I was able to interview so many of his comrades is that many of the people he impacted were half his age when he knew them. From their stories, a portrait emerges of someone dignified, uncompromising, and magnetic with a disarming smile, sense of humor, and gentle humility.

The impact he had varies depending on the stage of life and context in which people knew him. But one of the things that stood out is how much influence he had despite sometimes brief interactions. Ervin is one example. Through just two weeks together in prison, Sostre changed the trajectory of his life. Many young defense committee members also remember learning from his example despite only meeting in the courtroom or corresponding sporadically due to censorship.

While many referred to him as a symbol, they did so in an embodied way. He was a living example to them of what it meant to lead a life of continuous struggle. Sandy Shevack said Sostre taught him the difficult, daily work of revolution. It is not just showing up to a protest or engaging in an action; it means being there day after day to do the unglamorous labor necessary to build the world we want within the shell of the old. Sostre believed that only through demonstrating material structures and tangible results could people be won over to struggle. He often summed this up through a phrase I love for its simplicity: “If we do it right, it will end up right.” There are no shortcuts to liberation.

Garrett Felber is a Visiting Fellow in American Studies and the Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration at Yale.

Roberto Sirvent is Editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.