St. Louis County Prosecutor Wesley Bell delivers a speech on Jan. 21, 2019, in St. Louis. Photo: Michael Thomas for The Intercept

The AIPAC-backed challenger to Rep. Cori Bush also said the decision not to release killer cop Darren Wilson’s side of the story was “tragic.”

Originally published in The Intercept.

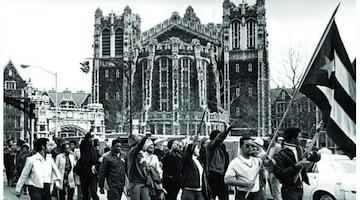

Three months after police officer Darren Wilson killed 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, setting off what became the Black Lives Matter movement, Wesley Bell — the current St. Louis prosecutor running to unseat Rep. Cori Bush — told a local news radio show that there wasn’t a strong racial divide in Ferguson.

Bell, who was serving as a municipal court judge and community college professor at the time, said he hoped Brown’s killing would “wake some people up” to get Black residents more engaged in their community and that the real “tragedy” of the situation was that the prosecutors hadn’t shared Wilson’s side of the story with the public, which was fomenting distrust in the process.

In Bell’s opinion, not releasing evidence that spoke to “the officer’s side of the story” was a mistake on the part of the prosecution. “To me that’s the tragedy of it — is that months later, I can’t even tell you whether I believe the officer should be indicted or not, because I don’t have the evidence,” Bell said.

Bell is now running with more than $8 million in backing from the American Israel Public Affairs Committee against Bush in the Democratic primary next week in Missouri’s 1st Congressional District. Bush rose to national prominence as a Black Lives Matter organizer in Ferguson. Bell was elected to Ferguson City Council in the first election following the surge of local protests, beating out a candidate supported by protester groups, and went on to unseat the St. Louis prosecutor, Bob McCulloch, whom he criticized in this interview for his handling of the Brown case.

Bell made the comments about Ferguson in November 2014 on the Nick Taliaferro Show, which went off the air in 2017. At the time, Bell was a municipal court judge in the small St. Louis suburb of Velda City, which was sued in 2015 in a federal civil rights case over running an unlawful bail system.

Brown’s killing wasn’t unique to Ferguson, Bell said during the radio segment. “These are issues that have been plaguing our country since the beginning of our country. So when I hear, ‘Well it’s just Ferguson, it’s just Ferguson,’ even in this area, it’s not just Ferguson. These issues have been happening all over our region, it’s just this particular one happened in Ferguson and that’s what’s been playing in the media.”

In the wake of Brown’s killing, there was a sense that the racial divide in Ferguson was comparable to that of Selma, Alabama, in the 1960s, Taliaferro said. “That’s just not the case,” Bell said. “In the United States, there is a racial divide. I think we agree with that. I’m saying, relatively speaking, Ferguson is not as bad.”

Ferguson’s racial divide was “less than normal,” Bell said, notwithstanding issues that still needed work, including diversity in the police force and government. But the need for accountability was “on both sides,” Bell said. “African Americans need to get more involved.” When he ran for a council seat, Black people weren’t involved in the political process, he said. “I’m hoping this wakes some people up.”

“That quote is pretty astonishing coming from not only a Black man in St. Louis but a Black man who lived in Ferguson and was a municipal court judge,” said Thomas Harvey, a civil rights lawyer who ran the nonprofit law firm in St. Louis that sued Velda City under Bell’s judgeship; Harvey is currently based in Los Angeles. “It’s also an indication of the deep racism in St. Louis that you could look at Ferguson and say, ‘It’s not that bad,’” Harvey said.

The Bell campaign commented on the 2014 interview in a statement. “Cori Bush and her allies are intentionally mischaracterizing Wesley’s comments,” wrote Anjan Mukherjee, a spokesperson for the Bell campaign. “In the interview, he was criticizing then-Prosecuting Attorney McCulloch for being secretive and not releasing the evidence on Wilson, a criticism he felt so strongly about, that he ultimately ran against McCulloch and beat him.”

Compared to other cities in Missouri at the time, it’s accurate to say that Ferguson was in the middle of the spectrum of unconstitutional practices and racist policing, according to Harvey. “It’s just that they were all so racist, it’s weird to hear someone say Ferguson wasn’t that bad. I think it’s actually indicative of how bad racism is in St. Louis overall and the whole region. What you’re doing is comparing it to the worst, most explicit forms of racism, and saying, that isn’t exactly happening in Ferguson.”

Arrest rates, police violence, stops, tickets, fines, and jailing were overwhelmingly disproportionately targeted against Black people living in Ferguson or passing through, Harvey said. “That is well known,” he added, and at the time, it was common knowledge.

Clients who lived in and near Ferguson would tell him that they wouldn’t travel to see friends and family around holidays because they didn’t want to get arrested and spend Thanksgiving or Christmas in jail, he said. Harvey said he used to work with pregnant women in St. Louis, many of whom didn’t want to drive to get prenatal care for the same reason. They arranged taxis instead.

“Wesley was a judge in a town where the exact same thing was happening,” Harvey said. The prevailing logic at the time was that it was better to have a Black judge who could empathize with the population even if the system was still operating in a racist way, Harvey said. “I think that just kind of reflects Wesley’s overall politics, which is, the system can still be racist, we can still be jailing people illegally, holding them for $50, exploiting them, destroying their lives, so long as there’s a sort of kinder, gentler person who is able to empathize with them when they come before the court.”

“That was really surprising to hear, especially that then it was 2014, after Mike Brown was murdered,” Harvey said. “This was common knowledge well before Mike Brown was murdered, and it was especially common knowledge among any Black person I met who lived in or around North County,” he said. “It’s just shocking to hear him say that. He must mean Ferguson isn’t the worst city in that region, and I agree, there are worse,” he said. “It’s hard to understand.”

Bell was elected St. Louis County prosecuting attorney against a three-decade incumbent with close ties to the local police. Bell was lauded as the first Black head prosecutor in the jurisdiction, someone who would champion the progressive reforms St. Louis had been pushing for since before Brown’s killing. Staff attorneys in the St. Louis prosecutors’ office were so angered by his win that they left the prosecutors union to join the local police union, The Intercept reported.

But Bell later disappointed supporters when he declined to charge Wilson in Brown’s killing after reviewing the case.

On the radio in 2014, Taliaferro asked Bell what he thought would happen if the grand jury decided not to indict Wilson. Bell said he didn’t think there was any chance Wilson would remain an officer in Ferguson, but that the “worst-case scenario” from a perspective of safety and unrest was if the grand jury decided not to indict. “There’s going to be some kind of violent response. It’s just a matter of how much. And obviously we’re all praying that it’s not a lot.” Bell said he believed in nonviolent protest “as opposed to violence.”

Last month as the race against Bush heated up, civil rights groups issued a report claiming that his office had not delivered on the reforms he promised on the campaign trail, and that the jail population had steadily climbed under his leadership.

“Wesley Bell has exposed himself as a fraud,” said Working Families Party spokesperson Ravi Mangla. “He’s running on being a Ferguson reformer, when it’s clear he couldn’t see the deep-lying issues in his own community.” WFP is backing Bush in the race.

Harvey, who was co-counsel on the suit over the bail system while Bell was judge in Velda City, said they would have sued Bell personally if they could have. “If judges didn’t have judicial immunity, we would have sued the judges in those cities,” he said.

“They’re very clearly participants in this system and know what’s happening, and are frequently the reason people are incarcerated,” Harvey said. “It’s ridiculous to think they don’t know. It’s impossible for Wesley Bell or any municipal court judge to say they didn’t know what was happening.”

Akela Lacy is a Politics Reporter at The Intercept. She was previously The Intercept’s inaugural Ady Barkan Reporting Fellow; prior to that, she was a Politics Fellow in the D.C. Bureau. She has also worked at Politico, covering breaking news and immigration. She produced Politico’s flagship newsletter, Playbook, and co-authored the afternoon newsletter, Playbook PM. Prior to that, Lacy worked in international reporting at the Pulitzer Center. She graduated from the College of William and Mary with a B.A. in sociology and Italian. She is based in New York.